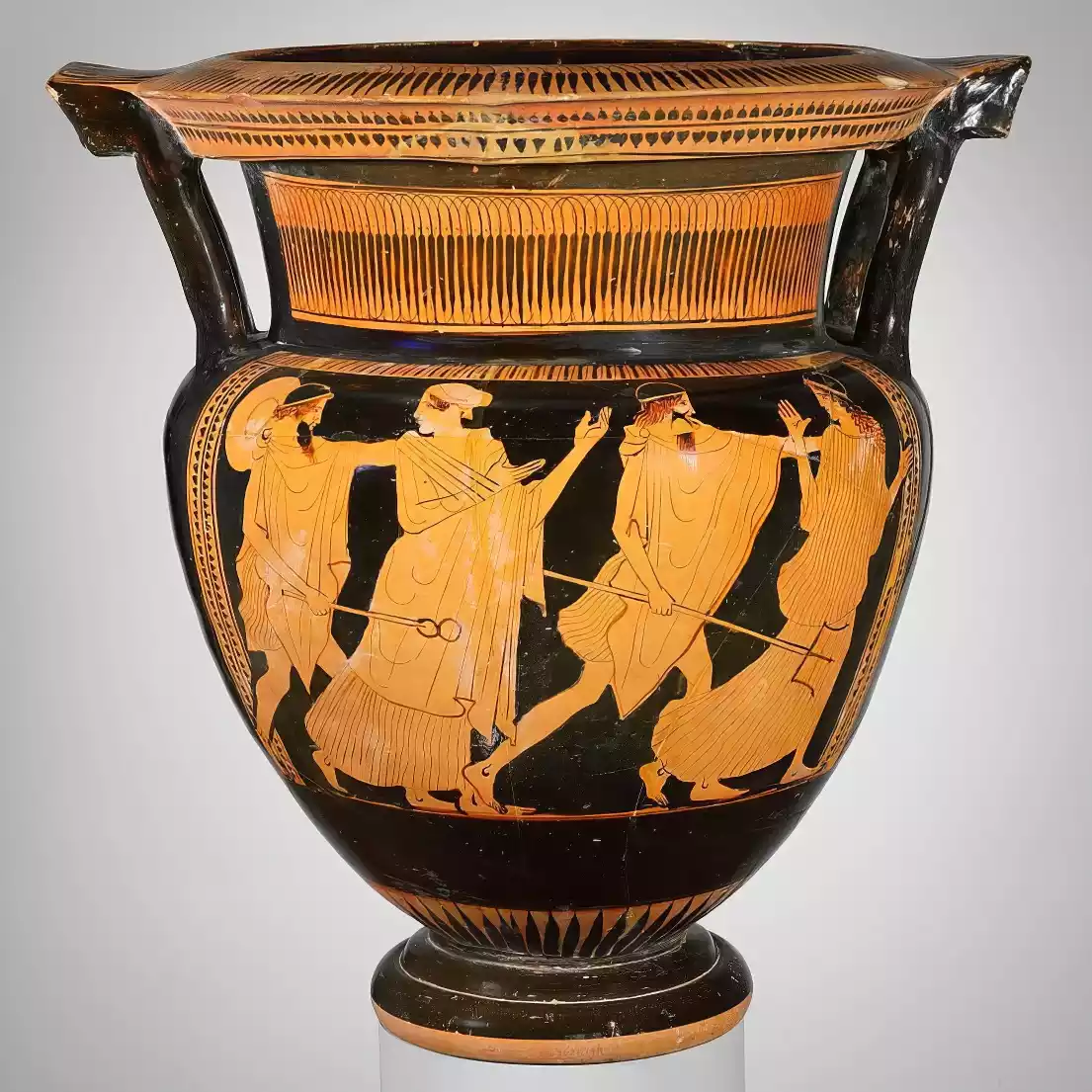

Attic red-figure column krater made of terracotta, around 460 BC, attributed to the Painter of Oporona.

The concept of the Twelve Gods is a fundamental element of ancient Greek religious perception and worldview. It refers to a divine complex of twelve dominant deities who resided on the snow-capped peaks of Olympus, the highest mountain in Greece, which symbolically functioned as the center of the world and a point of connection between heaven and earth. The Olympian gods shaped the cultural, religious, and artistic expression of the ancient Greeks for centuries, representing a complex projection of human virtues, weaknesses, and desires.

The composition of the Twelve Gods presents remarkable variations depending on the era and region, reflecting the evolutionary course of Greek religious thought. However, the most prevalent configuration includes Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, Athena, Ares, Aphrodite, Apollo, Artemis, Hermes, Hephaestus, and Hestia (although in some traditions Hestia is replaced by Dionysus). Each deity possessed specific fields of influence and supernatural powers (Paparrigopoulos), representing natural phenomena, social functions, and psychological dimensions of human existence.

In contrast to monotheistic traditions, the Olympian gods were characterized by anthropomorphism both in their physical form and in their psychological makeup. They exhibited passions, rivalries, loves, and conflicts, creating a complex mythological web that reflected the complexity of the human condition. The Twelve Gods constituted not only the foundation of religious practice but also an inexhaustible source of inspiration for art, literature, and philosophy.

The famous bust of Zeus from Otricoli, a Roman marble copy based on a Greek original from the 4th century BC. It is located in the Pio-Clementino Museum, Vatican, catalog number 257.

1. The Origin and Composition of the Olympian Twelve Gods

1.1 Theogony and the Emergence of the Olympian Gods

The genealogical origin of the Olympian gods is situated within an extremely complex cosmogonic framework. According to Hesiod’s Theogony, before the dominance of the Olympian gods, the world experienced successive generations of primordial deities. From the primordial Chaos emerged Gaia (Earth), Tartarus, Eros, Erebus, and Night. Gaia gave birth to Uranus, with whom she created the Titans, among whom were Cronus and Rhea, the parents of most Olympian gods (Konstantinidis).

The transition from the power of the Titans to the Olympian gods is mediated by the famous Titanomachy, a cosmic conflict that results in the victory of Zeus and his siblings. This mythological narrative captures the evolutionary course of Greek religious thought from primitive chthonic cults to more anthropomorphized deities, while also reflecting social changes and cultural conflicts. (Search for more information with the word: Titanomachy mythology Hesiod)

1.2 The Hierarchy and Organization of the Divine Pantheon

The Olympian Twelve Gods constitute an organized hierarchical system with Zeus holding the supreme position as “father of gods and men.” The authoritative structure of the ancient Greek pantheon represents a remarkable projection of the social and political structures of the time. As Paparrigopoulos states, the twelve main gods held distinct areas of influence, referring to a system of power distribution with specific responsibilities.

The international study of the Greek pantheon (Desautels) highlights how the composition of the twelve gods was a dynamic and not static formation. In different time periods and geographical areas, certain deities could be replaced by others, reflecting the particular priorities and values of each community.

1.3 Olympus as the Abode of the Twelve Gods

Olympus, the highest Greek mountain with its snow-capped peaks, served as the symbolic center of divine presence in the ancient Greek world. The establishment of the gods on Mount Olympus was not merely a geographical placement but a deeply symbolic act that defined the cosmological perception of the ancient Greeks. As noted in the study of the Twelve Gods of Olympus (Letsas), the mountain was elevated in the collective consciousness as the center of the universe and a point of connection between heaven and earth.

1.4 Different Versions of the Twelve Gods in Ancient Greece

The composition of the Twelve Gods presents remarkable variations depending on the region and historical period. While the core of the most important gods usually remained stable (Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Athena), there were different versions that included or excluded specific deities. For example, in some areas Dionysus replaced Hestia in the Twelve Gods, while in others Hades, although a brother of Zeus and Poseidon, was not included among the Olympian gods due to his chthonic nature. These variations reflect the diversity of Greek religious expression and the adaptability of the religious system to local needs and traditions.

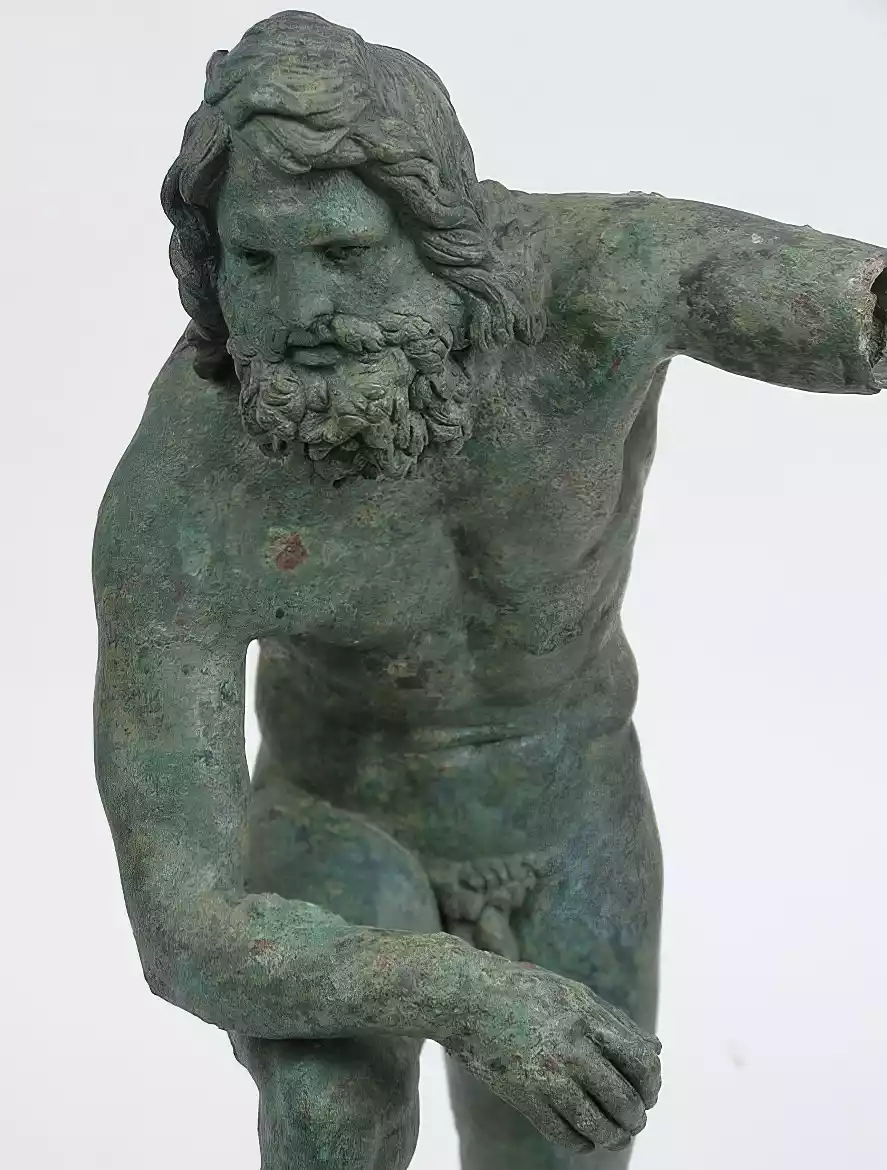

Bronze statuette of Poseidon, 2nd century AD, from the “Find of Ampelokipoi.” It depicts the god in a resting posture, with intense musculature and wet hair. Based on an original by Lysippus. National Archaeological Museum of Athens, no. find. Χ 16772.

2. The Dominant Gods of Olympus and Their Powers

2.1 Zeus and His Authority over Celestial Phenomena

Zeus, as the father of gods and men, held the supreme position in the hierarchy of the Twelve Gods, exercising absolute authority over celestial phenomena. His dominion extended to the control of weather conditions, with the most significant symbol of power being the thunderbolt, crafted by the Cyclopes as a gift for his victory over the Titans. The semantic analysis of the epithets attributed to him – “cloud-gatherer,” “thunderer,” “etherial” – reveals the multifaceted nature of his cosmic power. According to a related study by William Gladstone, Zeus’s position was established as primary among the Olympian deities from the early Homeric period.

His authority also extended to justice, as he was considered the supreme judge and protector of laws, hospitality, and oaths. This dual function of his, as a regulator of both natural and moral laws, reflects the progressive evolution of theological thought in ancient Greece towards a more anthropomorphized conception of divinity.

2.2 Marine and Chthonic Deities: Poseidon, Demeter, and Hades

After the distribution of cosmic power among the three brothers – Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades – Poseidon assumed dominion over the seas and waters. With the trident as his main symbol of power, he could cause tempests, tsunamis, and earthquakes, earning the epithet “Earth-shaker” (he who shakes the earth). Modern analysis of the Olympian gods (Helmold) highlights how Poseidon represented both the beneficial and destructive aspects of the water element.

Demeter, as the goddess of agriculture and fertility, played a vital role in ensuring human survival through the control of seasons and vegetation. The myth of the abduction of her daughter Persephone by Hades encapsulates the archetype of the cycle of vegetation, linking the chthonic dimension with the regeneration of life.

Hades, although often not typically included among the twelve Olympians due to his constant residence in his underworld realm, was an integral part of the cosmic triad of power. As the lord of the Underworld, he ruled over the souls of the dead and the chthonic riches, maintaining cosmic balance with his brothers. (Search for more information with the word: Triadic cosmic power ancient Greek religion)

2.3 Deities of War and Wisdom: Athena and Ares

Athena, born fully armed from the head of Zeus, embodied strategic intelligence, technical skill, and just warfare. Her powers combined wisdom with martial virtue, making her the protector of both warriors and craftsmen and philosophers. The dual nature of her responsibilities reflects a complex understanding of virtue in ancient Greek thought, where intellectual sharpness was considered as valuable as physical bravery.

In contrast, Ares represented the raw, violent side of war, the bloodshed, and the destructive frenzy of battle. As recorded in the texts about the Dii Olympii (Pollux), this bipolar representation of the phenomenon of war reveals the deep ambivalence of the ancient Greeks towards violence and military conflict.

2.4 Deities of Art and Beauty: Apollo, Aphrodite, and Hephaestus

Apollo, the god of light, music, divination, and medicine, embodied the aesthetic ideal of measure, harmony, and order. His powers extended from healing ability and prophetic knowledge to the high art that refines the human soul. The modern mythological study by Paul Decharme emphasizes how Apollo represented the balance between the rational and the intuitive elements in human consciousness.

Aphrodite, as the goddess of love and beauty, held power over romantic passions, reproductive power, and aesthetic pleasure. Her influence on human psychology was considered so strong that even the gods could not resist her charm.

Hephaestus, the lame god of fire and metallurgy, represented technological skill and the creative transformation of matter. Despite his physical disability, his ability to create marvelous objects and weapons for the gods made him irreplaceable in the divine pantheon.

2.5 The Triad of Daily Life: Hermes, Artemis, and Hestia

Hermes, as the messenger of the gods and psychopomp, held an intermediary position between different worlds and states. His powers included the protection of travelers, merchants, and thieves, as well as mediation between gods and humans, the living and the dead. The diversity of his functions reflects the need for mediation and communication at all levels of human experience.

Artemis, twin sister of Apollo, governed wild animals, forests, and hunting, while simultaneously protecting young girls and pregnant women. This seemingly contradictory coexistence of wildness and protective tenderness suggests the ancient Greeks’ deep understanding of the complex forces governing nature and human existence.

Finally, Hestia, the eldest of Cronus’s daughters, oversaw the sacred hearth and domestic harmony, serving as the foundation of social cohesion at both the family and city-state level. Although often downplayed in modern references, her significance in the daily worship practices of the ancient Greeks was fundamental.

The bronze statuette of Artemis, dating to the end of the 4th century BC, is an exceptional find of underwater archaeology. It was recovered from the waters of Mykonos in 1959 and reveals the multifaceted nature of the goddess. National Archaeological Museum of Athens, exhibition “Invisible Museum.”

3. The Influence of the Twelve Gods on Ancient Greek Culture

3.1 Worship Practices and Rituals towards the Olympian Gods

The worship of the twelve gods of Olympus permeated every aspect of daily life in ancient Greece through a complex web of ritual practices. The worship events included animal sacrifices, libations, prayers, and offerings, tailored to the specific characteristics of each deity and local traditions. According to the mythological study of Decharme, Greek religious practice was characterized by the absence of dogmatic rigidity and priestly hierarchy, allowing significant flexibility in the local expression of religiosity.

The Panhellenic worship was primarily manifested through major festivals, such as the Panathenaea in honor of Athena and the Olympics in honor of Zeus, which combined religious ceremonies with athletic and artistic competitions. These events served as means of enhancing social cohesion and cultural identity within and between Greek city-states. (Search for more information with the word: Panhellenic festivals ancient religion)

3.2 Architectural Monuments and Sanctuaries Dedicated to the Twelve Gods

The worship of the Olympian gods was monumentally reflected in architecture, with the construction of imposing temples and sanctuaries throughout the Greek world. The Acropolis of Athens with the Parthenon, the sanctuary of Olympian Zeus in Olympia, the sanctuary of Apollo in Delphi, and the Heraion in Argos are characteristic examples of the monumental expression of religious devotion.

The architecture of the temples followed specific patterns that reflected the perception of the nature of each deity. Thus, the temples dedicated to Zeus were often distinguished by their grandeur and imposing size, while those dedicated to Athena were noted for their harmony and aesthetic perfection. This architectural legacy not only attests to the spirituality of the ancient Greeks but also decisively shaped the evolution of the Western architectural tradition.

3.3 The Presence of the Olympian Gods in Art and Literature

The Olympian gods were protagonists of artistic creation, inspiring masterpieces of sculpture, vase painting, poetry, and drama. The iconography of the Twelve Gods is characterized by a gradual evolution from archaic, stylized representations to naturalistic, idealized forms of the classical period that reflected the perception of divine perfection.

In literature, the Olympian gods play a central role in the Homeric epics, in the works of the lyric poets, and in ancient drama. The complexity of their characters and their interactions with mortals provided a rich narrative material for exploring existential and moral issues that preoccupied ancient Greek thought.

3.4 The Survival and Evolution of the Twelve Gods in Modern Times

Despite the prevalence of Christianity and the official abolition of the Greek religion during the Byzantine period, the cultural influence of the Twelve Gods remained alive through art, literature, and philosophy. The Renaissance rekindled interest in Greek mythology, while the neoclassical movement revived the aesthetic standards and symbols of the ancient Greek pantheon.

In modern times, the Olympian gods continue to serve as a reference point in literature, cinema, visual arts, and popular culture, demonstrating the timeless power of these archetypes and their ability to be redefined according to the needs and aesthetic preferences of each era.

Marble head of Apollo from the Augustan or Julio-Claudian period (27 BC–68 AD), with an archaizing arrangement of hair reminiscent of statues from the end of the 6th and early 5th centuries BC. Gift of Jacques and Joyce de la Begassiere, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Different Interpretations & Critical Assessment

The study of the twelve gods of Olympus has been a field of multi-layered interpretative approaches from different research schools. Walter Burkert highlighted the anthropological dimensions of Greek religion, tracing its roots to prehistoric worship practices. In contrast, Jane Ellen Harrison focused on the chthonic origin of the cults, arguing for the priority of female deities in the early religious system. Claude Lévi-Strauss approached the Olympian gods as systems of symbolic structures reflecting social contradictions, while Karl Kerényi focused on the psychological dimension of myths. Jean-Pierre Vernant analyzed the Olympian gods as social constructs that reflect the evolving political structures of archaic and classical Greece. The ongoing dialectic between these different interpretative approaches enriches our understanding of the complex cultural significance of the Twelve Gods.

Black-figure amphora from the workshop of the Painter of Berlin 1686, circa 550-530 BC. It depicts the marriage of Zeus and Hera in a chariot accompanied by gods. On the other side, the conflict between Heracles and Cycnus with the intervention of Zeus. Origin: Kamiros, Rhodes. British Museum, no. 1861,0425.50.

Epilogue

The Twelve Gods of Olympus constitute a multifaceted system of worldview that transcends mere depiction of religious beliefs. It represents a symbolic representation of human effort to understand and organize the world through archetypal forms that embody natural phenomena, social functions, and psychological states. Its timeless allure lies precisely in this multi-layered nature, allowing for its interpretative approach from different perspectives.

The legacy of the twelve gods of Olympus continues to shape our collective imagination, fueling literature, art, and philosophical thought, even in an era of different cosmological quests. The archetypes embodied by the Olympian gods remain active in human consciousness, reminding us of the unbroken continuity of our cultural tradition and the search for meaning in our natural and social environment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who exactly were considered the twelve main gods residing on Olympus?

The exact composition of the Twelve Gods presents variations depending on the historical period and region. The most prevalent version includes Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Ares, Aphrodite, Hermes, Hephaestus, and Hestia. In some traditions, Hestia is replaced by Dionysus, while other sources mention different compositions depending on local worship traditions.

How did the powers of the Olympian gods reflect the needs of ancient Greek society?

The supernatural abilities of the gods of Olympus directly reflected the fundamental concerns and needs of the ancient Greeks. Zeus’s authority over weather phenomena was linked to agricultural survival, while Athena’s wisdom expressed the value of strategic thinking. Poseidon’s marine powers reflected the naval nature of many Greek cities, while Aphrodite’s influence on love echoed the recognition of the emotional and reproductive aspects of human existence.

Did the worship of the gods of Olympus differ among the various Greek city-states?

Despite the common recognition of the twelve Olympian deities, worship practices exhibited significant local variations. Each city-state had its own patron deities and festive traditions. Athena in Athens, Hera in Argos, Apollo in Delos and Delphi, were worshipped with different epithets and rituals that reflected local historical and social conditions, creating a rich mosaic of religious expressions.

What were the main rituals in honor of the gods residing on Olympus?

The worship of the Olympian gods included various ritual practices, with the most significant being animal sacrifices, libations (liquid offerings), processions, and competitions. Important Panhellenic festivals such as the Olympics in honor of Zeus, the Panathenaea for Athena, and the Pythia for Apollo combined religious ceremonies with athletic, musical, and dramatic contests. In daily life, ordinary citizens also performed household rituals and prayers.

How did the twelve gods influence the art and architecture of ancient Greece?

The Olympian deities served as a central source of inspiration for Greek artistic creation, determining the evolution of sculpture, vase painting, and architecture. The temples, designed with mathematical precision and aesthetic perfection, reflected the particular attributes of each god. The statues of the gods evolved from archaic, stylized forms to idealized, anthropomorphic representations that embodied the perception of divine perfection and harmony.

Bibliography

- Decharme, P. (2015). Mythology of Ancient Greece. Google Books.

- Desautels, J. (1988). Gods and Myths of Ancient Greece: Mythology. Google Books.

- Gladstone, W. E. (1858). Olympus: or, The religion of the Homeric age. Google Books.

- Helmold, G. (2007). Olympian Gods and Heroic Legends: The Complete Works. Google Books.

- KONSTANTINIDES, G. (1876). Homeric Theology, or, the Mythology and Worship of the Greeks. Google Books.

- Letsas, A. N. (1949). Mythology of the Earth (Vol. 1). Google Books.

- Paparrigopoulos, K. (1860). History of the Greek Nation: from the most ancient times. Google Books.

- Pollux, I. (1824). Iulius Pollux’s Onomasticon: with annotations of interpreters. Google Books.