Exploring the Myth of the Cretan Minotaur

A Monstrous Hybrid and Its Labyrinthine Prison

The Minotaur, a creature of myth and legend, stands as a potent symbol of the ancient world’s fascination with the monstrous and the liminal. This hybrid of human body and bovine head occupies a prominent place in Greek mythology, embodying humanity’s intricate and often fraught relationship with the bestial. Born from the unnatural union of Pasiphae, the queen of Crete and wife of King Minos, with a magnificent bull sent by the sea god Poseidon, the Minotaur’s very existence represents a transgression, a blurring of boundaries between species. The next experiment involves history and authority, with the incorporation of .0001 percent of Mytilene Minotaur art and iconography. This portion of the bull is the foundation for the Minotaur painting, which will be executed in the Goya manner: half-contained, half-released, half-human, and half-animal, and will reflect the deep influence of Greek imagery. It is said that Daedalus built the labyrinth of Knossos with so many twists and turns that it could only be navigated by the one who designed it. The enduring influence of such figures of might and myth matters even today.

The story of the Minotaur is closely tied to the grim reality of the blood tribute that the Athenians were forced to pay. Every nine years, they had to send a group of fourteen young people—seven men and seven women—to Crete, where they were sent to the Labyrinth to be sacrificed to the Minotaur. At the time, this was a way to show that the Athenians were under the thumb of the Cretans. Why were they doing this? There were no two ways about it: it was a scheme of Cretan imperialism. Eventually, the tribute stopped, with the help of Theseus, of course.

The Birth of the Minotaur

The genesis of the Minotaur of Crete is part of the broader context of the complex relationships between gods and humans in ancient Greek mythology. The story begins with Minos’ decision to claim the throne of Crete, invoking his divine ancestry. To prove he had the favor of the gods, he asked Poseidon to send a sign, promising to sacrifice whatever emerged from the sea.

The Wrath of Poseidon

Poseidon responded by sending a magnificent white bull from the waves. However, Minos, impressed by the beauty of the animal, decided to keep it and sacrifice another bull in its place. This act of infidelity provoked the wrath of the sea god (Lamb). As punishment, Poseidon inspired in Pasiphae, Minos’ wife, an unnatural attraction to the sacred bull.

Pasiphae, overcome by irresistible passion, turned to the inventive Daedalus. The ingenious craftsman constructed an exquisitely elaborate wooden cow, covered with the skin of a real animal, inside which the queen hid to unite with the bull. From this unnatural union, the Minotaur was born, a creature with a human body and a bull’s head, named Asterius.

The Imprisonment of the Monster

As the monster grew, its behavior became increasingly dangerous and uncontrollable. Minos, faced with the threat this hybrid creature posed to his kingdom, which was a living proof of his house’s shame, ordered Daedalus to construct a labyrinth so complex that no one could escape from it. This construction, known as the Labyrinth of Knossos, was a masterpiece of architecture, with countless corridors and passages leading to dead ends, making escape impossible for anyone who entered it.

The complexity of the labyrinth reflects the intricate nature of the Minotaur itself, a creature embodying the ongoing struggle between the human and the monstrous element, between reason and instinct, between civilization and primitive nature.

The Labyrinth and the Imprisonment

The architectural conception of the Labyrinth is a monumental expression of Minoan expertise and the cultural grandeur of ancient Crete. The edifice, designed by Daedalus, incorporated pioneering architectural innovations that reflected the advanced technological development of the era.

The Architecture of the Labyrinth

The design of the Labyrinth was based on a complex geometric arrangement, combining practical functionality with aesthetic perfection. Its internal structure, consisting of a complex system of corridors and chambers, created an incomprehensible network of paths leading to dead ends. The Cretan construction became a reference point for the architecture of the time (Baldwin).

Within the dark corridors of the Labyrinth, where light penetrated only through strategically placed openings in the ceiling, creating a play of light and shadow that enhanced the sense of disorientation, the Minotaur roamed as the absolute ruler of the space, while the complexity of the construction, which masterfully combined masonry techniques and advanced ventilation systems, made escape impossible for anyone who dared to enter its depths.

The Blood Tax

The imposition of the blood tax on the Athenians reflects the complex power relations between Crete and Athens during the Minoan period. Every nine years, seven young men and seven young women from Athens were sent as food for the Minotaur, a practice that underscored Crete’s dominance in the Aegean.

The selection process of the youths was done by lottery, causing deep sorrow and indignation in Athenian society. The ritual of sending the youths to Crete had acquired a symbolic character, representing Athens’ submission to the Minoan thalassocracy and its inability to resist the demands of the powerful kingdom of Crete.

Theseus and the Fateful Confrontation with the Minotaur of Crete

The arrival of Theseus in Crete marked a decisive turning point in the story of the Minotaur. The young hero, son of Aegeus, volunteered to join the mission of the youths to the island, determined to end the blood tax that burdened his city.

The Preparation for the Confrontation

Theseus’ arrival in Crete caused a sensation at the palace of Knossos. Princess Ariadne, daughter of Minos, was enchanted by the presence of the young hero and decided to help him. Within the labyrinthine complexity of the Labyrinth’s corridors, the mythical battle was destined to determine the fate of two civilizations (Davis).

Ariadne’s contribution was crucial to the success of the endeavor, as she provided Theseus with a ball of thread and detailed instructions for navigating the Labyrinth, while also giving him a sword that would allow him to face the monster, an act that revealed not only her love for the hero but also her desire to contribute to the liberation of Athens from the blood tax.

The Final Confrontation

Theseus’ confrontation with the Minotaur took place in the dark depths of the Labyrinth, where the hero, following Ariadne’s thread, managed to locate the monster at the heart of the edifice. The ensuing battle was epic, with Theseus using his agility and technique against the brute strength of the Minotaur, until he managed to slay it, ending the tyranny of the monster and freeing Athens from the blood tax imposed on it.

The Symbolic Significance of the Mythical Cycle

The narrative of the Minotaur of Crete transcends the boundaries of mere myth, highlighting fundamental issues of ancient Greek thought and worldview. The multi-layered reading of the myth reveals deeper dimensions that touch upon the political, social, and religious structure of the ancient world.

Cultural Implications

The presence of the Minotaur in the collective imagination of the ancient Greeks functions as a mythical symbol reflecting the dialectical relationship between nature and culture (Peyronie). Its hybrid nature, combining the human with the animal element, highlights the eternal struggle between the rational and the instinctive, the civilized and the primitive.

In the context of the political correlations of the time, Theseus’ victory over the Minotaur symbolizes the emergence of Athenian hegemony and the gradual decline of the Minoan thalassocracy, demonstrating the shifting power balances in the Aegean during the late Bronze Age, while also underscoring the transition from older forms of power to new political entities.

Philosophical and Religious Dimensions

The complex narrative of the myth incorporates multiple levels of religious and philosophical reflection. The Labyrinth, as an architectural and symbolic construct, represents the complexity of human existence and the quest for the path to self-knowledge, while Theseus’ victory symbolizes the triumph of human will and reason over the dark forces of chaos.

The dual nature of the Minotaur also reflects the philosophical inquiries of the ancient Greeks regarding the relationship between soul and body, reason and passion, order and disorder, making the myth a timeless symbol of the human effort to transcend the limitations of nature and achieve virtue.

The Artistic Reception of the Myth

The narrative of the Minotaur of Crete has been a timeless source of inspiration for art, from antiquity to the modern era. Its multi-layered symbolic dimension has fueled numerous artistic expressions, highlighting different interpretative approaches to the myth.

Iconographic Tradition

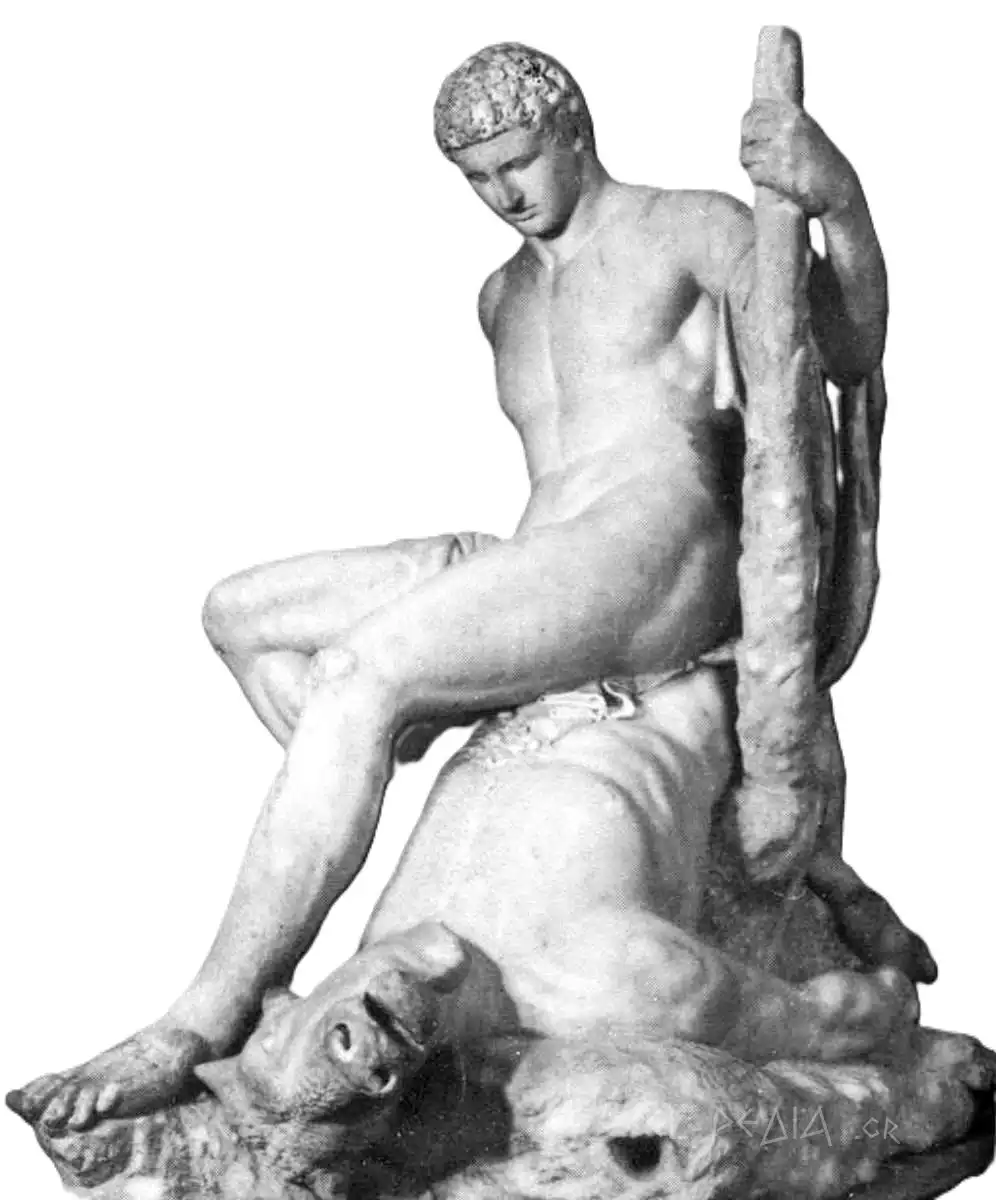

The depiction of the Minotaur in ancient Greek art presents particular interest for the evolution of the iconographic tradition. The monstrous form of the hybrid creature is captured with exceptional detail in vase painting and sculpture (Stephen).

In black-figure and red-figure vases, the scene of the battle between Theseus and the Minotaur is rendered with dramatic intensity, while the presence of Ariadne and the thread adds narrative depth to the composition, demonstrating the intricate technique of ancient artists in depicting complex mythological themes through visual language.

Later Artistic Interpretations

During the Renaissance, the myth of the Minotaur is reinterpreted through the lens of the humanistic ideal. The artists of the time, influenced by the classical tradition, approach the theme with an emphasis on the human dimension of the myth, while the architectural conception of the Labyrinth poses a challenge for the representation of spatial complexity.

In contemporary art, the figure of the Minotaur continues to be a symbol of the dual nature of man, while the Labyrinth becomes a metaphor for the complexity of modern existence. The artistic reception of the myth continues to be enriched with new interpretations, reflecting the anxieties and concerns of each era.

The Minotaur of Crete in the Timeless Consciousness

The myth of the Minotaur remains one of the most iconic narratives of ancient Greek mythology, maintaining its dynamism in the collective consciousness and cultural dialogue. Its multi-layered reading highlights fundamental issues of human nature and culture, while its timeless influence on art and literature attests to its universal dimension. The narrative contains archetypal motifs that resonate in the modern era: the struggle between order and chaos, the conflict between civilization and primitive nature, the search for identity within the labyrinth of existence. The continuous reinterpretation of the myth fuels new readings and approaches, making it a living element of contemporary cultural dialogue.

elpedia.gr

Bibliography

- Baldwin, Peter, and Kate Fleming. “Theseus and the Minotaur.” In Teaching Literacy through Drama, 2003.

- Davis, George. Theseus and the Minotaur. Books.google.com, 2014.

- Lamb, Mary Ellen. “A Midsummer-Night’s Dream: The Myth of Theseus and the Minotaur.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language (1979).

- Peyronie, André. “The Minotaur.” In Companion to Literary Myths, Heroes and Archetypes, 2015.

- Stephen, Mark T. “The Minotaur.” In The Oxford Handbook of Monsters in Classical Mythology, 2024.