The Greek Revolution of 1821 was a milestone for European diplomacy and a decisive factor in reshaping international relations in the 19th century. The Holy Alliance, formed by the conservative forces of Europe after the fall of Napoleon, viewed the Greek uprising as a direct challenge to the post-Napoleonic order. The political dynamics that developed within this confrontation largely determined the outcome of the Greek issue.

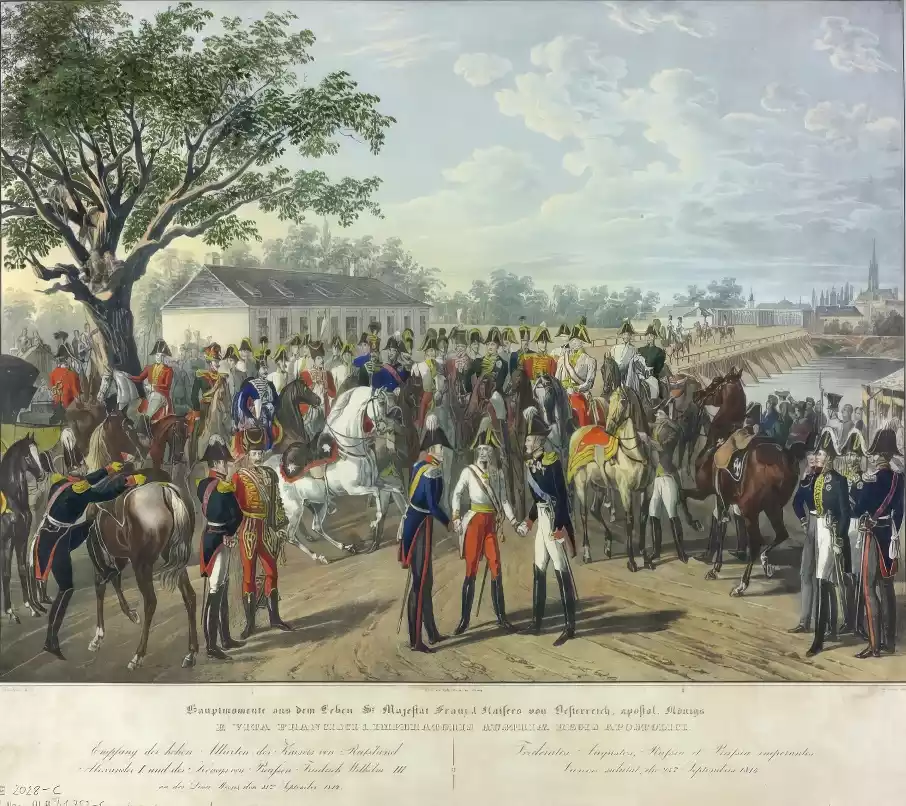

The formation of the Holy Alliance, spearheaded by Tsar Alexander of Russia, Emperor Francis I of Austria, and King Frederick William III of Prussia, aimed to ensure European stability after the Napoleonic upheavals. However, the emergence of national liberation movements, with the Greek one being prominent, tested the principles of diplomatic cooperation among European powers.

The Greek revolution of 1821 acted as a catalyst that highlighted the contradictions in the policy of the Holy Alliance, as European powers found themselves divided between the principles of conservatism and the pressures of the emerging Philhellenic movement. Austrian Chancellor Klemens von Metternich, a central figure in European diplomacy of that period, viewed the Greek struggle as a serious threat to the regime established after the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

The reaction of European powers to the Greek issue was not uniform but was shaped by complex geopolitical factors, religious sympathies, and economic interests. The final outcome of the struggle, which led to the recognition of Greek independence, reflects the shifting balances in European diplomacy and the growing influence of national movements in shaping the international political scene of the 19th century.

The Holy Alliance and Its Principles

Formation and Fundamental Principles

The Holy Alliance was officially formed on September 26, 1815, primarily initiated by Tsar Alexander I of Russia and under the guiding influence of post-Napoleonic European diplomacy. The Alliance’s agreement was initially signed by three monarchs, the Tsar of Russia, Emperor Francis I of Austria, and King Frederick William III of Prussia. The nature of the pact was officially religious-political, based on the principles of the Christian doctrine and the divine origin of monarchical power.

The fundamental principles of the Holy Alliance reflected the counter-revolutionary spirit of the era and the will of Napoleon’s victors to establish a system of European security that would prevent the re-emergence of revolutionary movements. As Thanos Veremis characteristically notes in his study, the monarchies of Europe sought to maintain the existing legitimacy and ensure the monarchical principle as a key pillar of the political order (Veremis).

Maintaining the Post-Napoleonic Order

Maintaining the political order established by the Congress of Vienna was a primary concern of the Holy Alliance. Post-Napoleonic Europe was reorganized based on the principle of legitimacy and the preservation of pre-revolutionary dynastic rights. The Alliance developed a system of diplomatic vigilance and military readiness to address any threat to the regime.

The collective security mechanism established provided for regular congresses of European powers (Aachen 1818, Troppau 1820, Laibach 1821, Verona 1822) to assess the European situation and take coordinated measures against revolutionary threats. The diplomacy of the time was characterized by close cooperation among the great powers, with the dominant influence of Austrian Chancellor Metternich, who emerged as the main architect of the conservative order (Schroeder).

The Stance Towards Revolutionary Movements

The stance of the Holy Alliance towards the revolutionary movements of the time was categorically negative. The principles of conservatism and monarchical legitimacy imposed the suppression of any form of political dissent that could disrupt the European balance. The Alliance faced the revolutionary movements in Spain, Italy, and Portugal with decisive military interventions aimed at restoring monarchical power.

Under this perspective, the outbreak of the Greek Revolution of 1821 caused intense concern within the Holy Alliance. The Greek uprising against the Ottoman Empire presented European powers with a complex dilemma: on the one hand, the principle of legitimacy and the maintenance of the status quo demanded the condemnation of the revolutionary movement, on the other hand, the Christian identity of the Greeks and the sympathy of European public opinion towards their struggle created strong pressures for a differentiated approach. Managing this contradiction would be a decisive factor for the evolution of European policy towards the Greek Revolution.

Metternich’s Diplomacy Towards the Greek Revolution

The Initial Position of Austria and Metternich

Klemens von Metternich, Chancellor of Austria and a central figure in post-Napoleonic European diplomacy, faced the Greek Revolution with intense skepticism and hostility. His initial stance was shaped by two fundamental parameters: his adherence to the principles of the conservative order and his deep concern for maintaining the geopolitical balance in the Eastern Mediterranean.

For Metternich, the Greek uprising constituted a violation of the principle of legitimacy, as it was directed against the Sultan’s authority. According to his political philosophy, revolutionary movements, regardless of justification, were destabilizing factors for the European order. The Austrian Empire, as a multi-ethnic state, was particularly concerned about the prospect of spreading national liberation ideas, which could undermine its cohesion.

As noted by Vlasis Vlankopoulos in his historical analysis, Metternich’s policy towards the Greek Revolution was consistently oriented towards defending Austria’s interests and the regime of the Holy Alliance (Vlankopoulos).

Diplomatic Maneuvers and Political Pressures

Metternich’s diplomatic strategy towards the Greek Revolution manifested through a series of complex maneuvers. Initially, he attempted to persuade other European powers to adopt a common stance of disapproval of the revolutionary movement, invoking the principles of the Holy Alliance. At the Congress of Laibach (1821), Metternich exerted intense pressure for the formation of a unified European policy that would condemn both the Greek and other revolutions in Italy and Spain.

At the same time, the Austrian chancellor developed a network of diplomatic initiatives aimed at limiting international support for the Greeks. Austrian diplomatic missions in European capitals were instructed to treat the Greek issue as an internal matter of the Ottoman Empire, in which European powers had no right to intervene.

The Discrepancy Between Official Policy and Public Opinion

Metternich’s stance was in stark contrast to the wave of sympathy that developed in European public opinion in favor of the Greek struggle. In almost all European countries, intellectuals, artists, and liberal politicians openly expressed their support for the Greeks and their condemnation of the policy of conservative forces. The Philhellenic movement was an early expression of the influence of public opinion on international politics.

Metternich was forced to address this discrepancy between the official diplomatic line and popular sentiments, trying to limit the influence of Philhellenism in official circles. However, the growing popularity of the Greek cause created new pressures on European regimes and limited the effectiveness of Metternich’s diplomacy.

The Geopolitical Calculations of Austrian Diplomacy

Beyond ideological concerns, Metternich’s policy towards the Greek Revolution was also determined by geopolitical calculations. The Austrian Empire, which had significant economic interests in the Eastern Mediterranean, was particularly concerned about the implications of a potential collapse of the Ottoman Empire on regional balance.

More concerning for Metternich was the possibility of Russian intervention in favor of the Greeks, which would enhance Russian influence in the Balkans and upset the strategic balance in the region. Consequently, a significant part of Metternich’s diplomacy focused on preventing unilateral Russian intervention by maintaining the unity of European powers and diplomatic pressure on St. Petersburg.

The Limits of Metternich’s Influence

The stance of Austrian diplomacy and Metternich personally towards the Greek Revolution ultimately revealed the limits of his influence. Despite his systematic efforts to limit international support for the Greeks, the dynamics of the Philhellenic movement, the geopolitical rivalries among the great powers, and the evolution of the revolution itself gradually led to a shift in European policy.

The ability of the Greeks to sustain their struggle despite initial diplomatic adversities, combined with the gradual differentiation of British and Russian policy, led to a new phase in European diplomatic developments, where Metternich’s influence and that of the Holy Alliance significantly receded. The Greek Revolution ultimately emerged as a first significant crack in the edifice of the post-Napoleonic order built by the Austrian chancellor.

The Shift in European Policy

The Pressures of the Philhellenic Movement

The gradual reshaping of European policy towards the Greek Revolution is inextricably linked to the emergence and spread of the Philhellenic movement in European societies. This movement, which developed as a multifaceted expression of solidarity towards the Greek struggle, managed to create a new framework for understanding and interpreting the Greek issue, beyond the limitations of the official diplomacy of the Holy Alliance.

Philhellenic activity manifested in multiple ways: formation of support committees, organization of fundraisers, publication of texts and articles, artistic creation, and, in some cases, voluntary participation of Europeans in military operations. The presence of Philhellenic committees in most European capitals served as a constant reminder of the Greek issue, exerting pressure on governments to modify their stance. (Search for more information with the keyword: Philhellenic movement Europe 1821)

Particularly significant was the contribution of prominent European intellectuals and artists, such as Lord Byron, Victor Hugo, Eugène Delacroix, and many others, who gave the Greek struggle an ideological legitimacy that transcended the negative assessment of the Holy Alliance. The creation of a national state on the ruins of Ottoman rule became a central goal of Philhellenic activity.

From Indifference to Intervention

The shift in European policy towards the Greek Revolution gradually manifested through a series of diplomatic initiatives reflecting the changing balances among the great powers. The initial indifference or even hostility of European governments gradually receded in the face of new geopolitical conditions that developed in the Eastern Mediterranean.

A decisive role in this shift was played by the Russo-British rapprochement after the death of Tsar Alexander and the accession of Nicholas I to the Russian throne in 1825. The Protocol of St. Petersburg (April 1826) was the first step in internationalizing the Greek issue, as the two powers agreed to mediate for the restoration of peace and the granting of autonomy to the Greeks.

The escalation of diplomatic interventions continued with the Treaty of London (July 1827), which France also joined, thus forming a tripartite alliance for the imposition of a ceasefire and the promotion of a political solution. This diplomatic development marked the definitive departure from the principles of the Holy Alliance and the failure of Metternich’s policy on the Greek issue.

The Battle of Navarino and Its Consequences

The Battle of Navarino (October 20, 1827) marked the culmination of the shift in European policy and the definitive internationalization of the Greek issue. The joint naval intervention of the three powers (Britain, France, Russia) and the destruction of the Turko-Egyptian fleet radically changed the dynamics of the Greek revolution, providing substantial military support to the Greek struggle.

The consequences of the battle were catalytic for the evolution of the Greek issue. This event was followed by the Russo-Turkish War (1828-1829), which further limited the Ottoman Empire’s ability to suppress the Greek revolution. The process of international negotiation that eventually led to the establishment of an independent Greek state with the Protocol of London in 1830 reflected the complete revision of the initial stance of European powers.

This development was a significant defeat for the policy of the Holy Alliance and particularly for Metternich, who saw the principles of the conservative system he had so fervently defended retreat in the face of new political realities. The emergence of the Greek state marked the beginning of the end for the system of the Holy Alliance and the start of a new era in international relations, where national movements would gain increasing importance.

Different Interpretations & Critical Assessment

The historiographical assessment of the Holy Alliance’s stance towards the Greek Revolution presents significant variations among researchers. Some historians, such as Dakin and Woodhouse, view this policy as an expression of pure conservatism and adherence to the doctrine of maintaining the status quo. In contrast, Kremmydas and Svoronos highlight the economic and geopolitical factors that influenced the stance of European powers.

The newer historiographical school, represented by scholars like Petropoulos and Kitromilides, approaches the issue through the lens of the ideological transformations of the era, highlighting the dialectical relationship between conservatism and liberalism. The complexity of the phenomenon is also reflected in the research of McGrew and Angelopoulos, who focus on the interaction of diplomatic, social, and cultural factors in shaping European policy towards the Greek issue.

Epilogue

The stance of the Holy Alliance towards the Greek Revolution of 1821 was a complex historical phenomenon, reflecting the deeper trends of European diplomacy in the early 19th century. The contradictions and oppositions that developed in the context of addressing the Greek issue reveal the limits and internal contradictions of the post-Napoleonic order.

The gradual shift in European policy from initial hostility to active support for Greek independence marked the beginning of the end for the system of the Holy Alliance and the emergence of a new framework of international relations, in which national movements would play a decisive role. The success of the Greek Revolution, despite the initial reaction of conservative forces, foreshadowed the deeper changes that would transform the European map during the 19th century.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who were the main factors of the Holy Alliance towards the Greek Revolution?

The main factors of the Holy Alliance that shaped the stance towards the Greek issue were Tsar Alexander of Russia, Emperor Francis I of Austria, and King Frederick William III of Prussia. A decisive role was played by Austrian Chancellor Klemens von Metternich, who was the main theorist and inspirer of the Alliance’s conservative policy, seeking to maintain the post-Napoleonic order in Europe.

Why did the Holy Alliance initially face the Greek revolution with hostility?

The initial hostility of the Holy Alliance towards the Greek liberation struggle was based on the fundamental principles of conservatism it advocated. The Greek revolutionary movement was seen as a threat to European stability and the principle of legitimacy, as it challenged the Sultan’s authority. Additionally, the Alliance’s powers feared that the success of the Greek movement would encourage similar uprisings in other parts of Europe, undermining the regime established after the Congress of Vienna.

What was the contribution of the Philhellenic movement to the shift in European policy towards the Greek struggle?

The Philhellenic movement contributed decisively to the change in the stance of European powers towards the Greek Revolution, creating a favorable climate in European public opinion. The actions of intellectuals, artists, and liberal political circles throughout Europe gave the Greek struggle an ideological and cultural dimension that transcended the narrow framework of diplomacy. Philhellenic committees exerted significant pressure on their governments, contributing to the gradual revision of official policy.

How did geopolitical rivalries affect the diplomacy of the Holy Alliance towards Greece?

Geopolitical rivalries among European powers played a decisive role in the allied diplomacy towards the Greek issue. Particularly the rivalry between Russia and Austria in the Balkans influenced the positions of the two empires. Russia, despite its initial adherence to the principles of the Holy Alliance, had a traditional interest in the Orthodox populations of the Ottoman Empire and sought to expand its influence in the region, a fact that particularly concerned Metternich.

What were the most significant diplomatic events that led to the change in the stance of European powers?

The pivotal diplomatic points in the evolution of the European stance towards the Greek revolution include the Protocol of St. Petersburg (1826), the Treaty of London (1827), and the Battle of Navarino (October 1827). The death of Tsar Alexander and the accession of Nicholas I to the Russian throne (1825) accelerated developments, leading to Russo-British rapprochement. The Russo-Turkish War (1828-1829) and the Protocol of London (1830) completed the process of international recognition of Greek independence.

What did the success of the Greek Revolution signify for the system of the Holy Alliance?

The successful outcome of the Greek liberation struggle was the first significant crack in the edifice of the conservative post-Napoleonic order established by the Holy Alliance. The recognition of the independent Greek state marked a substantial deviation from the principles of legitimacy and the maintenance of the status quo, highlighting the limits of the Holy Alliance system. This development foreshadowed deeper changes in the European political scene, with the increasing importance of national movements in shaping international relations.

Bibliography

- Veremis, Th. (2018). 1821: The creation of a nation-state. Athens.

- Vlankopoulos, Vlasēs M. (1998). Odyssey of 146 years 1821-1967: treaties-milestones of history. Athens.

- Kitromilides, P. M., & Tsoukalas, C. (2021). The Greek Revolution: A Critical Dictionary. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pradt, D. G. F. de R. de P. de F. de (1822). Europa und Amerika im Jahre 1821 (Vol. 2). Leipzig.

- Schroeder, P. W. (2014). Metternich’s Diplomacy at its Zenith, 1820-1823: Austria and the Great Powers in the Post-Napoleonic Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.