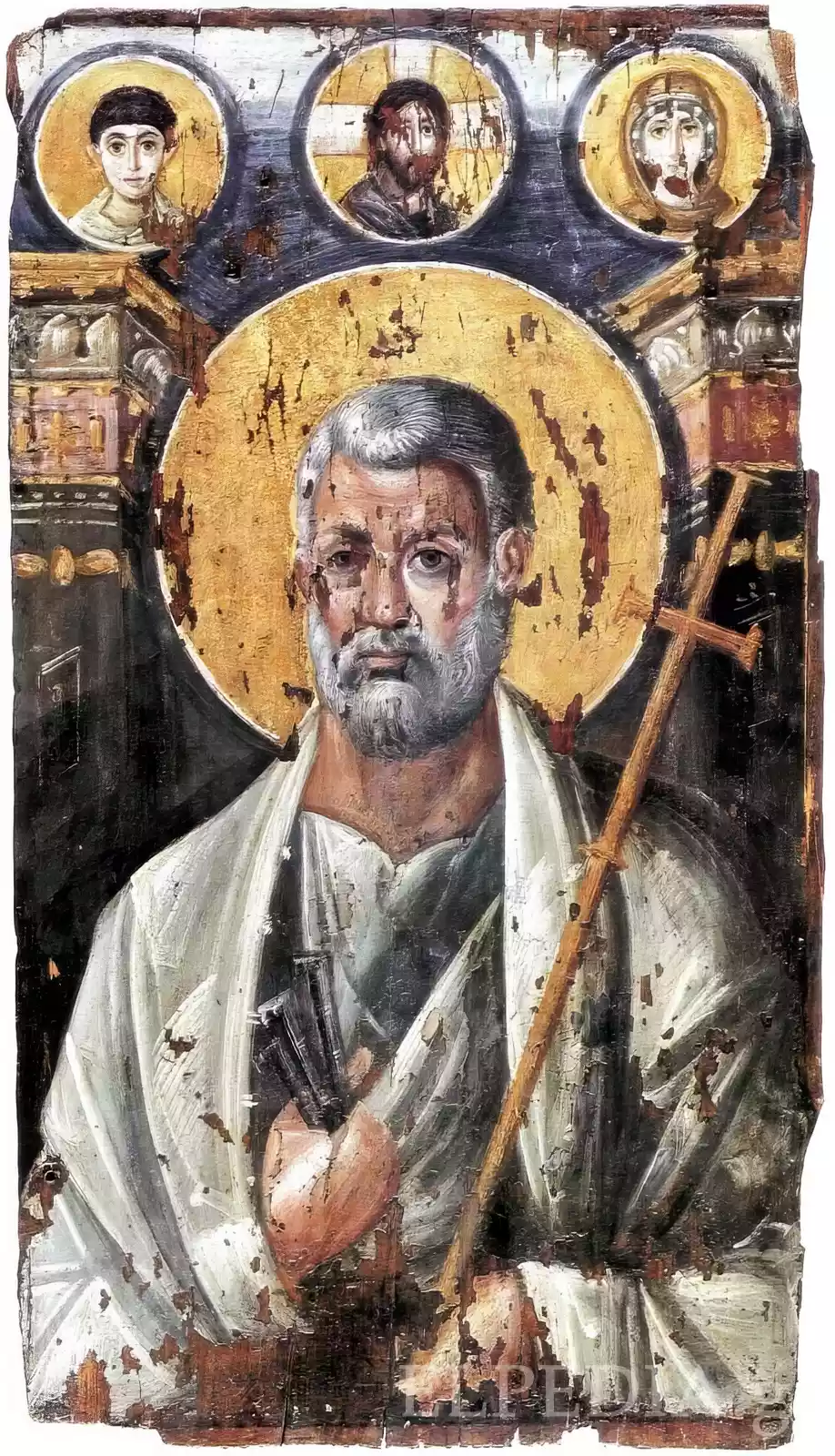

The Saint Peter encaustic icon stands as an extraordinary exemplar of early Byzantine sacred art, demonstrating remarkable technical sophistication and spiritual gravitas. This work of art, created in the late 6th or early 7th century CE in the encaustic technique, stands alongside the other masterpieces of Christian iconography that came out of that momentous period. Its exquisite condition—one of the few respects in which it can be said to rival, or even to surpass, the other paintings of the first millennium—to this day elicits gasps of wonderment from viewers.

The massive dimensions of the icon—92.8 x 53 centimeters—guarantee its commanding presence. It offers an image of an apostle—Saint Peter, the figure in the niche nearly declares—in a way that is nearly full portrait and set against an architectural backdrop that allows for just enough depth to make the icon suitable for a body orientation toward the viewer without it being too obtrusive. One can almost read the image’s invitation to “pose yonder, haloed and lintel-high as half-length your famous representational likeness.” And above Peter, three figures in pointed archways, who could just as easily be meditating companions to the acting apostle, make it clear no mortal made it this far without divine sanction.

This piece clearly demonstrates the fusion of Hellenistic naturalism and the emerging Christian iconographic conventions that were developing at this time. The diptych draws from the late antique consular diptychs and turns the secular imperial imagery of those works into sacred Christian portraiture. Stylizing the figure of Saint Peter with a remarkable optical depth, it both retains and enhances the psychological presence Hellenistic portraiture has long achieved. Saint Peter seems to emerge from the pictorial plane and into the optical space of the beholder—an effect enhanced by the light and shadow modeling of his weathered visage. Counters to his optical emergence are the pictorial flatness and the frontal presentation of the two figures in the upper medallions.

Origins and Historical Framework of Saint Peter Encaustic Icon

The Saint Peter encaustic icon stands as a pertinent example of the sophisticated artistic achievements of the late 6th or early 7th century CE and is emblematic of a key transitional moment in Christian sacred art. This major work, currently housed and preserved at Saint Catherine’s Monastery at the base of Mount Sinai, reflects the technical mastery reached by Byzantine painters in the so-called pre-iconoclastic period. The very distinctive qualities of encaustic painting, which involves mixing pigments with heated wax and then using the wax to paint, allowed artists not only to retain the rich, sumptuous quality of color (C. M. Nims) that we see in this artwork but also to create textures and effects that are as vibrant now (Ramaekers) as they were when the icon was first completed.

The icon’s creation is wrapped in the multiplicity of historical contexts that involve the complex interactions between imagery created by the Roman Empire and the early visual traditions of Christianity. Artists during this transformative time took established forms of imperial portraiture and adapted them to serve as new modes of religious representation. The distinctive niche backdrop of the architectural setting draws on the visual language of late antique official portraits (particularly consular diptychs) while transforming those secular conventions into sacred vehicles for new religious meanings.

The development of Christian iconography in the 6th-century Mediterranean underwent significant changes that would define religious art for many years. These changes are reflected in the icon’s composition—when artists began establishing standardized ways of depicting sacred figures. Yet, as with earlier forms of religious art, the icon maintained classical connections. And technically, the early Byzantines had reached the artistic peak of sophistication in religious portraiture. An encaustic icon, while not overly naturalistic, was painted within the parameters of a traditional portrait and, as such, held as much authority as the figure it portrayed (D. F. Williams).

The monastery’s strategic location at the crossroads of numerous cultural influences contributed greatly to the unusual traits of the icon. The exquisite quality of the artwork, so skillfully executed, makes it seem almost miraculous that such a work could survive the centuries to remain intact to the present day. Yet here it is; and in the preserved context of the work, scholars can make out a rich narrative of the events surrounding the very making of the icon in the first place. And not just any narrative—the icon’s context speaks to its momentous significance, a concept that in itself is laden with multiplicities of possible interpretations.

Icon scholars have identified certain technical and stylistic features of the work that firmly place it within the context of pre-iconoclastic Byzantine art. Encaustic is a notoriously difficult medium to master, yet the artist who created the Saint Catherine icon not only handled it with the highest level of sophistication but also, by most accounts, executed the work in ways that traditional art historians might have deemed as heretical (i.e., a portrait of a religious figure that is evocative of a naturalistic type). And yet, judging from the appearance of St. Catherine’s face in the icon, that is exactly what the artist did.

Composition and Technical Achievement

The technical artistry of this Saint Peter encaustic icon is manifest in two main ways. One is the distinctive handling of the encaustic medium. The other is the thoughtful arrangement of the composition, where all the elements serve to direct the viewer’s focus toward the central figure of Saint Peter. Even in less skilled hands, working with encaustic has the potential to produce remarkable effects because of the medium’s unique optical properties (M. Lidova).

Saint Peter is not only present but also commanding in Judith’s portrayal. Although half-length, he nevertheless seems to extend into our space in a most intimate way. One speaks of a painting having a “tight” composition, when the elements are balanced, unified, and function together as a kind of visual “whole.” In this regard, the only problem I see with this tight composition is the double problem that the two half-medallions present, with their unsightly seams, do for both the figure of Saint Peter and the composition as a whole. Another word one might use to describe this composition, which employs so many binding devices, is that it is “clothed” with binding devices. Indeed, Judith has clothed this composition so snugly that the painting nearly achieves the status of an altarpiece.

The artist’s deftness with the encaustic medium becomes especially clear in the rendering of Saint Peter’s features; the brushwork is so well controlled that it has the appearance of modeling. This is next-level skill, even for the standards of the early Byzantine period, when painters were just beginning to explore the possibilities of dimensionality in the human form. The artists of this time were, after all, more concerned with the iconic presence of a figure than with the physiognomic veracity that earlier Roman portraitists had prized. And yet, here is a work that gives us a sunburned but also very bronzed Saint Peter, whose deep recessive gaze somehow manages to express both the “thingness” of a human figure and the allusive divine presence of an apocalyptic vision that’s just around the corner.

This masterwork’s technical complexity is revealed through an examination of its various compositional components. The artist had to keep the exacting temperatures required for the application of the heated, wax-based pigments necessary for encaustic painting, which involves a very specific medium that’s relatively easy to mess up if you don’t know exactly what you’re doing (B. Gehad). Because this artist did know what she was doing, however, she was able to achieve an unprecedented level of subtlety and skill in her modeling of this icon’s various surfaces so that they could best function in reflecting light and thus creating the “presence” effect that is the whole point of the thing.

The aesthetic and theological purposes of each aspect of the artwork are clear. The architectural setting is reminiscent of not just imperial portraiture, but also the places in which such works would have been situated. It is balanced and harmonious, lending an air of stability that hints at the actual content of the work—it is a portrait of someone not just with “authority,” but also with a kind of authority that is intended to last, to give the Christian community a sense of permanence. The “technical mastery” of the artist is evident, not just in “the work,” but also in what the work represents: the unity of the Christian community under the kind of “spiritual power” that is far more important than mere physical or political power and presence.

Iconographic Significance and Sacred Symbolism

The complex symbolism present in this Saint Peter encaustic icon conceals many layers of pre-iconoclastic Byzantine art, with their characteristic ineffable ecclesiastical and theological meanings. Here we see a powerful half-length format for Saint Peter, not so very different from earlier Roman portraits, except that we are more accustomed to seeing these kinds of divinely authoritative figures from the front. What really jumps out, though, are Peter’s attributes and the symbolism of the elements surrounding him, all of which speak to a powerful moment in Christian history.

Traditional symbols of Peter’s apostolic office are present in the representation. The cross-staff and the keys of heaven acquire added significance through their placement in the sacred hierarchy of the composition. These objects, rendered with attention to their symbolic weight, establish Peter’s unique position as the keeper of heaven’s keys and the shepherd of Christ’s flock. Their treatment here gives visual expression to profound theological understanding. The cross-staff affirms Peter’s role as a cross-bearing martyr who triumphed with Christ at the Resurrection. The heavenly backdrop behind him reinforces the idea that he has access to the keys of heaven.

The three medallions arranged spatially around Peter’s figure convey the precise spiritual relationships that medieval people would have instantly recognized. Christ holds the center position, with the Virgin Mary and the youthful Apostle John on either side. They form a kind of heavenly court approving and sanctioning Peter for what he does down here. The golden backgrounds give these figures an appearance that clearly lights them up as the heavenly presences that, of course, they are meant to signify. The blue background, darkening toward the bottom, does more than provide a pleasing transition between the medallions and the architecture below. It also establishes a terrific celestial-to-terrestrial transition and a somewhat implicit power dynamic.

This masterwork illustrates the early Christian transformation of imperial imagery into religious symbolism. The work’s overall context—its architectural setting, with its carefully rendered niche, drawing upon traditions of official portraiture—retains the old meanings while infusing them with new, spiritual significance. Even in an age when portraiture was stylized, the artist’s realistic treatment of Peter’s features might have been understood by 5th-century viewers as achieving an unprecedented intersection of divine authority and human experience.

The original function of the icon, given its monumental size and the number of ways it exhibits technical skill, was surely something like what we have today when we speak of an “icon” within a “space” for some manner of public or private worship. Indeed, if we take the scale and presence of the Polyeuktos icon seriously, it was surely something on the order of a hefty sounding board for the liturgical “space” of the Monastery of the Polyeuktos, the church for which it was “commissioned,” if you will. The next obvious question is: What were the fine points of those functions in those domains of public or private worship that the icon might have served when it was “new”?

The preservation of this icon in the very meaningful site of Saint Catherine’s Monastery adds yet another layer to the rich symbolism of the piece itself. This profound site, located at the foot of Mount Sinai (where Moses received divine law), creates potent connections between Old and New Testament figures of authority. Geographically and spiritually, there are few places on earth so linked to the rich history of sacred art, and thus few to whom the monastic community could present such a remarkable artistic statement and expect it to be understood and appreciated.

Artistic Mastery in Sacred Portraiture

The exceptional detail in the face of Saint Peter demonstrates extraordinary technical ability in early Byzantine encaustic painting. The artist shows a nearly flawless command of human anatomy and a profound understanding of human psychology. The subtle modeling of the form, from the fleshy warmth of the facial features to the shadowy planes that seem to recede all too naturally, gives the head an easy three-dimensionality. Life radiates. The gaze, for which the careful placing of highlights and shadows does not even begin to account, creates a space that seems to connect directly with whomever is on the receiving end.

The artist’s dazzling technique is clear in the treatment of Peter’s skin tones, where layers of pigmented wax create effects that are almost too naturalistic for comfort – indeed, we find ourselves at a moment of discomfort when we confront what is a dictatorship of the naturalistic in color and texture. Yet the sophisticated treatment of this surface allows us to avoid any moment of obviousness in our encounter with the work: here is a moment when the color and texture of Peter’s skin allow us both to be close and also to acknowledge that these are the conditions of being close without closing in.

This detail goes beyond mere technical accomplishment to capture the complex nature of apostolic authority in early Christian art. The slight asymmetry of Peter’s features, the weathered quality of his skin, humanize the saint while preserving his dignified bearing. This powerful synthesis of earthly experience and divine calling may be the highest achievement of pre-iconoclastic Byzantine portraiture.

When we look closely at this amazing early Byzantine masterpiece, we are blessed with invaluable insight into the complex development of pre-iconoclastic Christian art that allows for both theological sophistication and artistic merit. The preservation of this encaustic icon at Saint Catherine’s Monastery is a rare gift that lets us glimpse the technical wonders achievable by still-living artists purportedly working at the “crossroads” of classical and Christian traditions. What is perhaps most astonishing, however, about this monumental artifact is not just its awe-inducing presence and remarkable virtuosity, but also its exemplary far-reaching significance.

The icon’s lasting influence comes from its marvelous blend of naturalistic depiction and spiritual symbolism, generating a visual vocabulary that would dominate religious art down through the medieval period. Its superior treatment of the encaustic medium, very much in evidence in the refined rendering of Saint Peter’s features, shows off talents that would not be seen again for hundreds of years. But most stunning of all is the fact that this piece expresses a moment that is all too rare in Christian history. It graphically gets across the notion that the very best in artistic achievement is what ought to serve the highest ends of religious devotion and community life.

elpedia.gr

Bibliography

K. Innemée – L’apport de l’Egypte à l’histoire des techniques. Cairo, 2006

L. Drewer – Studies in Iconography, 1996

M. Lidova – Word of image: Textual frames of early Byzantine icons, 2020

B. Gehad – Molten Versus Punic Encaustic, 2022