Title: Fresco of Saint Kosmas the Poet

Artist: Unknown

Type: Fresco

Date: Late 14th century

Dimensions: Unknown

Materials: Fresco

Location: Holy Monastery of Valsamonero, Crete

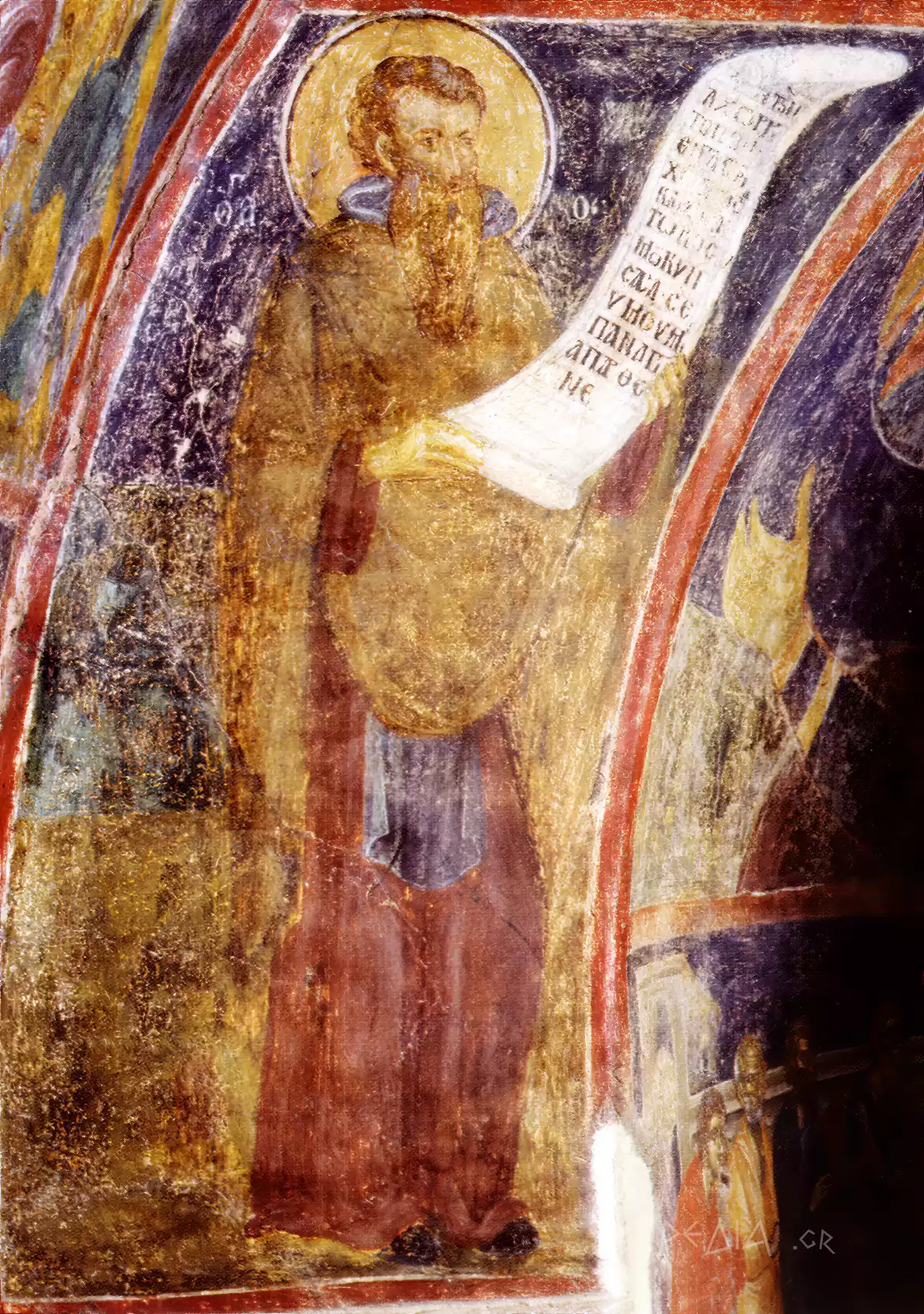

In the holy church of Panagia Odigitria of the Monastery of Valsamonero in Crete, the iconic fresco of Saint Kosmas the Poet stands out, an exceptional example of late Byzantine art from the last decades of the 14th century. The figure of Saint Kosmas the Poet is depicted with particular mastery, highlighting his spiritual character and hymnographic quality. The fresco is part of a broader iconographic program completed around 1400, just before the opening of the arched communication openings with the nave of the Forerunner. The technique of fresco used highlights the artist’s skill and dedication to the tradition of Byzantine iconography.

Stylistic Analysis and Iconographic Elements

The fresco of Saint Kosmas the Poet in the Monastery of Valsamonero is an exceptional example of late Byzantine art. The figure of the Saint is depicted with particular detail, holding a scroll that indicates his hymnographic quality. The colors, despite the wear of time, still retain their original vibrancy, with dominant earthy shades of brown and ochre.

The composition is characterized by an impressive balance between the monumental character and the detailed rendering of facial features, while the technical execution reveals an artist with deep knowledge of the Monastery of Valsamonero and its artistic traditions (M CONSTANTOUDAKI).

A particularly interesting aspect of the fresco is its adaptation to the architectural space, as the opening of the arched communication openings towards the nave of the Forerunner, which took place around 1400 and before 1407, significantly affected the arrangement of the figures and the overall composition of the iconographic program, resulting in some scenes being adapted with admirable skill to the new architectural conditions, as seen characteristically in the case of House Y’ on the south side of the arch.

The stylistic analysis also reveals the existence of different painting phases, with the frescoes of the north wall belonging to a later period, as indicated by the thicker layer of plaster used compared to the overlying depictions of the houses of the Akathist, while the prophets and saints in the two spandrels present remarkable stylistic homogeneity with the figures of the north wall.

Noteworthy is also the attention to detail that characterizes the rendering of garments and folds, as well as the excellent use of light and shadow to render the volume and plasticity of the figures, elements that testify to the artist’s high technical training and deep knowledge of the Byzantine iconographic tradition.

Historical Context and Artistic Tradition

The historical context of the last decades of the 14th century in Crete shaped a unique artistic environment. In the Monastery of Valsamonero, the fresco decoration evolved gradually, with work starting from the eastern side of the church and progressing westward.

This period is characterized by intense artistic activity in Crete, where different stylistic traditions meet. The fresco art of the time reflects the cultural fermentations taking place on the island, combining elements of the Byzantine tradition with new artistic trends (D Jiménez-Desmond).

The iconographic program of the church of Panagia Odigitria constitutes a complex narrative developed in different chronological phases, with the frescoing of the Sanctuary presupposing the opening of communication openings with the nave of the Forerunner, a fact dated to 1407, while the completion of work on the north wall, where prophets and saints are depicted in the two spandrels, presents remarkable stylistic homogeneity with the figures of the north wall, indicating a later phase of decoration.

Particularly interesting is the adaptation of the frescoes to the new architectural conditions created after the opening of the arched openings, as seen characteristically in the case of House Y’ on the south side of the arch, where the composition has been adapted with admirable skill to the surface created above the western communication opening with the new nave, while for the position of the figures of the scene, the curve below the arch is taken as a given, resulting in the enthroned Christ, in a sideways position, and the two hierarchs on the right following its shape.

The study of the different layers of plaster and their application techniques reveals the gradual evolution of the decorative program, with the thicker layer of plaster on the frescoes of the north wall indicating a later phase, while the absence of an older painting layer in specific areas confirms the initial dating of the frescoes around 1400.

Symbolism and Theological Extensions

In the composition of symbols in the church of Panagia Odigitria, a multi-layered approach is discerned. Saint Kosmas the Poet is depicted holding the scroll, an element that underscores his hymnographic identity and his didactic presence in ecclesiastical tradition.

Within the complex network of iconographic elements, a particular connection is observed between the different zones of the frescoing. In the case of House S’, for example, where Christ’s right foot and the angel’s figure appear to be “cut,” the artist’s effort to adapt the depictions to the available curved surface is highlighted, without this being due to the construction work of opening the openings.

The architecture of the space and the fresco decoration coexist in a harmonious relationship that highlights the deeper spiritual dimension of the whole (JS POZO-ANTONIO). This relationship becomes particularly evident in the case of Houses R’, S’, and T’ on the south side of the arch, where the figures of the Virgin and the rhetoricians in House R’ are artfully adapted to the available space.

The absence of repairs or thicker plaster on these specific frescoes, as well as the non-revelation of an older painting layer, suggests that the 24 houses of the Akathist were depicted after the opening of the communication openings with the new nave of the Forerunner, placing their dating close to 1400.

The study of the different phases of frescoing reveals a complex approach to conveying spiritual messages, with the frescoes of the north wall belonging to a subsequent phase, as indicated by the thicker layer of plaster used compared to the overlying depictions of the houses of the Akathist, while the prophets and saints in the two spandrels present remarkable stylistic homogeneity with the figures of the north wall.

Artistic Brilliance in Cretan Frescoes

The late 14th-century artistic character of Crete vibrantly flourished, much like the Elizabethan cultural climate of exchange. Saint Kosmas the Poet figures prominently in an impressive array of works that make up the Monastery of Valsamonero’s “wider iconographic scheme.” As with the acclaimed works of Crete’s contemporary artists, Kosmas’s portrayal gives impressive—if not irrefutable—evidence that this monastery’s artistic output corresponded with similar evidence of a vibrant cultural osmosis across the archaic sites of Crete.

When we look closely at how the fresco was done, we can see that it was begun on the eastern side of the space and finished on the western side, in a kind of deliberate progression. This is not a haphazard way to work, and it makes one think that whoever was responsible for the design of the fresco was also possessed of some pretty major craft skills. It’s also a progression that makes sense, both logistically and, as we’ll see, in terms of the narrative of the fresco itself. This fresco describes the heavenly realm. If you’re in this space, it’s going to be daytime, and if you’re going to go from one side of the space to the other, from east to west, you’re going to pass through a section of the sky that describes the heavenly bodies at midday, high noon.

The significance of Cretan art in molding the Byzantine tradition’s evolution is brought into sharper focus with a look at the different layers of frescoing (M CONSTANTOUDAKI). The images of Houses R’, S’, and T’ on the south side of the arch, each with a unique interpretation of the limited space, serve as the perfect example of the artists’ technical mastery in uniting the iconographic program and the church’s architecture. This seamless combination of art and architecture is what great artistic movements—like the one Cretan art was part of—are best known for; it is the something that set the movement apart because iconic works were notable not only for their painting but also for their thoughtful place within the framework of a larger structure.

The painting process at the church of Panagia Odigitria, with its sequential phases moving from east to west, shows a neatly ordered decorative program. A careful look at the plaster layers and their application methods reveals a very “deliberate” structure. For example, the thick plaster layer on the north wall frescoes indicates a late phase of work. This finding implies that the decorative artists were still working on that wall as they were creating the east wall frescoes. In fact, they seemed to be moving back and forth in the north-south direction, employing a shaft-of-light technique to increase the natural appearance of their 3D figures.

In some sections, the lack of an earlier painted layer supports dating the frescoes to circa 1400. Equally important is the observation of the stylistic consistency between the prophets and saints making appearances in the two spandrels on the north wall. These wall figures do not resemble the “proxy” personas seen in the prophets and saints that were part of a prior ill-fated attempt at frescoing the Barbara Chapel; instead, the wall figures seem cut from the same cloth as the spandrel prophets and saints. And that cloth appears to be Cretan.

The Significance of Saint Kosmas the Poet in Cretan Art

The study of the fresco of Saint Kosmas the Poet in the Monastery of Valsamonero highlights the significance of the monument in the evolution of Cretan art. The particular technique of frescoing, with successive phases and careful adaptation to the architectural space, testifies to the island’s high artistic tradition. The dating of the work around 1400 makes it an important milestone in the evolution of Byzantine art in Crete. The absence of older layers and the stylistic homogeneity of the different parts of the decoration suggest a well-organized artistic program. The study of the fresco contributes to understanding the artistic currents of the time and highlights the significance of the Monastery of Valsamonero as a center of artistic creation in medieval Crete.

elpedia.gr

Bibliography

M CONSTANTOUDAKI, Alexios and Angelos Apokafkos, Constantinopolitan painters in Crete. Documents from the State Archives in Venice (1399-1421). Bulletin of the Christian Archaeological Society, 2022.

D Jiménez-Desmond, JS Pozo-Antonio. “The fresco wall painting techniques in the Mediterranean area from Antiquity to the present: A review.” Journal of Cultural Heritage, 2024.