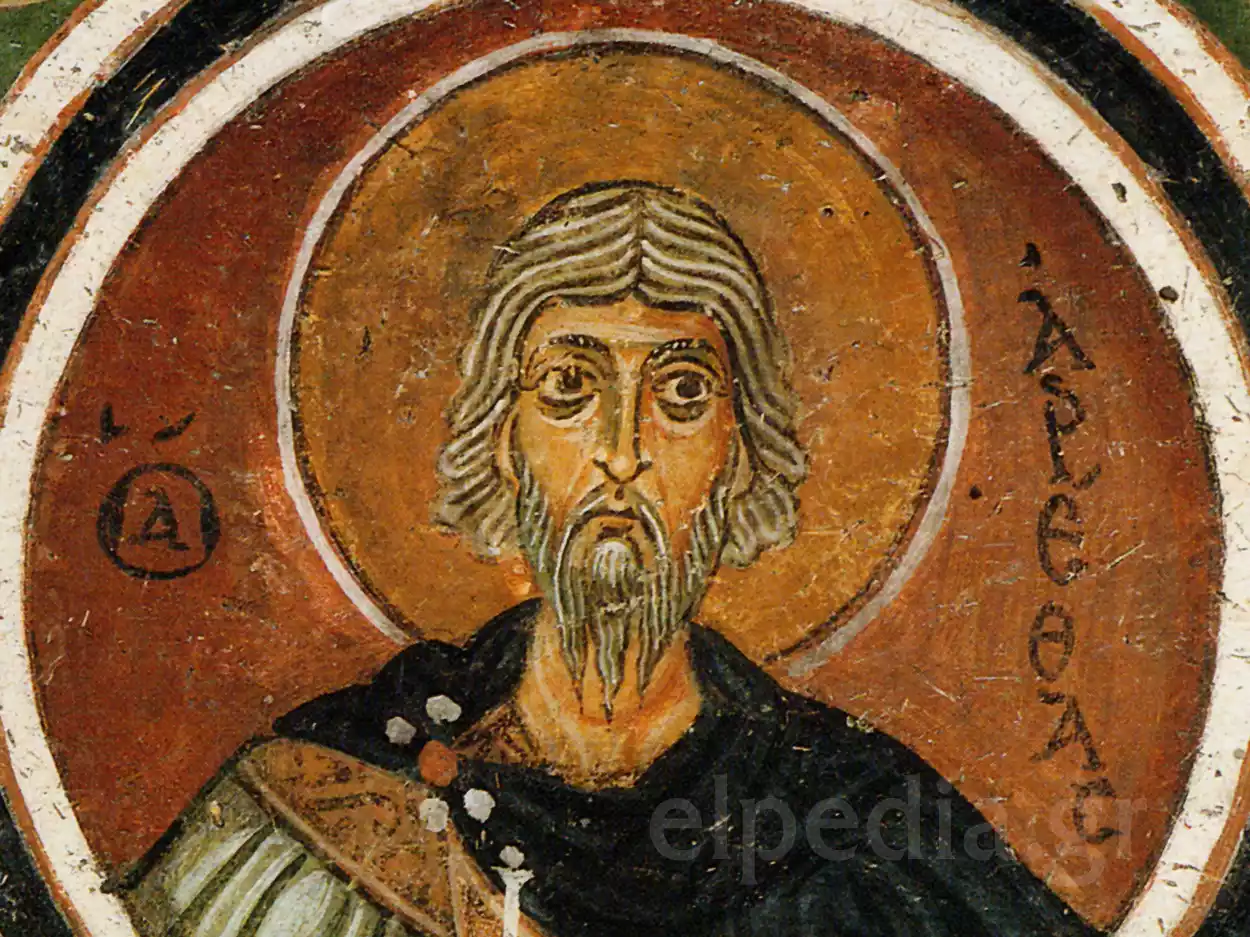

The well-preserved fresco of Saint Arethas, a martyr of the 6th century, adorns the southern side of the central ceiling in the crypt of the Monastery of Hosios Loukas (11th century).

Title: Saints George, Unconquered, Vincent, and Arethas

Artist: Unknown

Type: Fresco

Date: Third quarter of the 11th century (c. 1050-1075)

Materials: Not specified (probably natural pigments in wet plaster)

Location: Crypt, Katholikon of the Monastery of Hosios Loukas, Boeotia

A Journey into the Crypt of Hosios Loukas

The Monastery of Hosios Loukas in Boeotia is one of the most splendid monuments of Middle Byzantine art and architecture, a place where faith meets artistic expression in a unique way. Descending into the evocative atmosphere of the crypt of the katholikon, the visitor (even the online one, through the images) feels transported to another era. The crypt, a space for burial but also for worship, hosts an exceptional cycle of frescoes dating back to around the mid-11th century. Among the figures that adorn the cross-vaults of the ceiling, we find an impressive quartet of saints in the southern section: the martyrs Unconquered, Vincent, and alongside them, Saint Arethas. This depiction, along with the other figures of saints, apostles, and holy ones, composes a numerous choir that seems to emerge from the decorated, almost paradisiacal, plain of the ceiling, silently participating in the funeral service that was held there. The depiction of Saint Arethas in the Monastery of Hosios Loukas, along with the other military saints, provides us with valuable information about the art, theology, and history of the time, ideally capturing ideals and models that shaped Byzantine society. The study of these figures, as well as the Lives of Saints that have been compiled over the centuries, helps us to understand more deeply the world of Byzantium.

The Choir of Saints in the Crypt

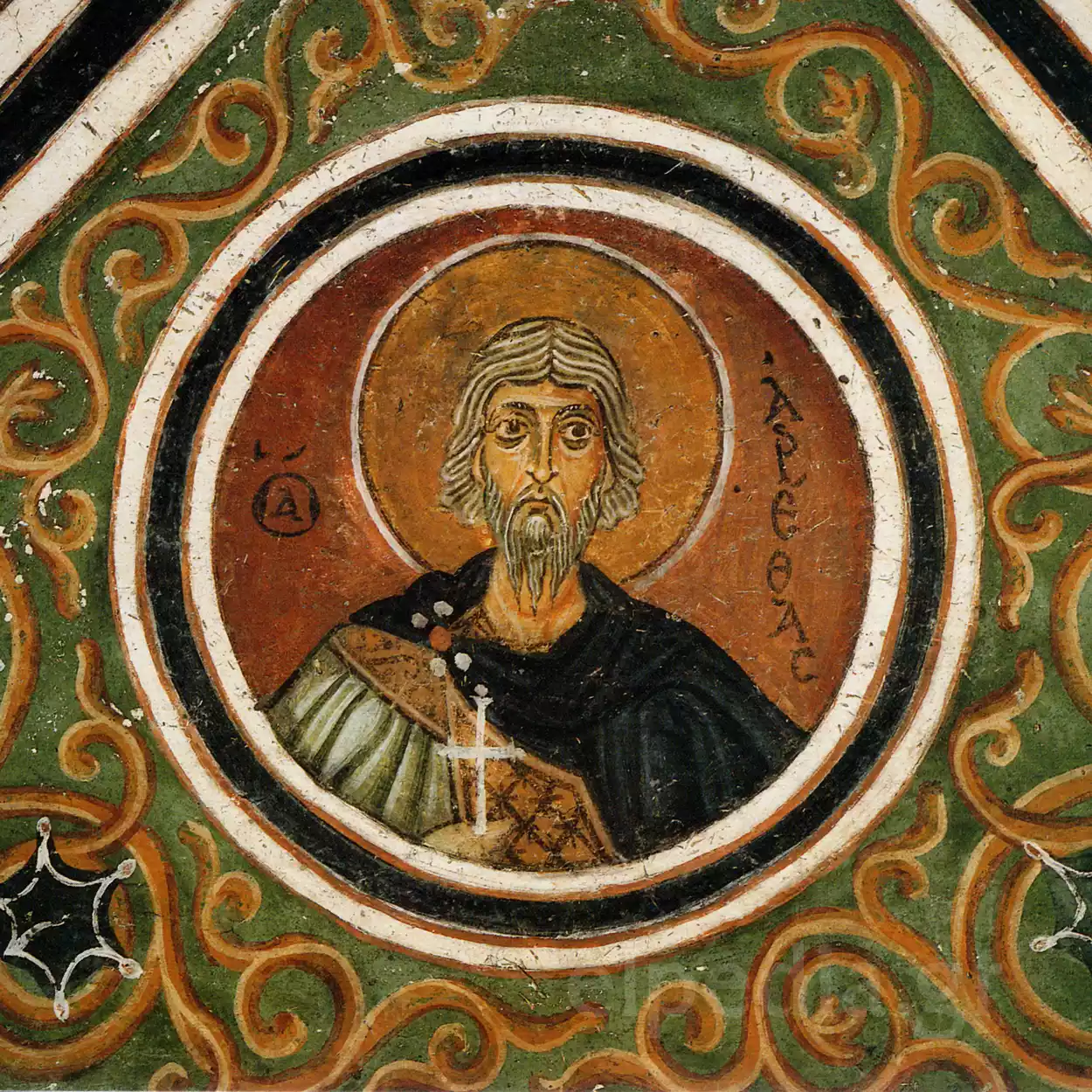

Walking mentally through the crypt of the Monastery of Hosios Loukas (Archaeological Bulletin), we encounter a unique iconographic program. In the ten cross-vaults that form the ceiling, an entire heavenly city unfolds. Quartets of saintly figures, depicted in circular medallions, are axially aligned, as if “floating” with an eternal order over a richly decorated, symbolically paradisiacal, plain. This heavenly army includes apostles, martyrs, military saints, and holy ones, a numerous choir that is directly connected to the Deesis (the well-known Trinity with Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the Forerunner) in the central apse. The whole ensemble seems to echo the funeral service, reminding us of the purpose of the space.

The Military Saints and the Position of Saint Arethas

The martyrs and military saints hold a prominent position, adorning the three central cross-vaults along the North-South axis. All are depicted in the same standardized, yet imposing manner: frontal, strictly facing forward, wearing luxurious garments adorned with paragaudia (vertical purple ribbons that indicated rank) and bearing a chlamys (cloak) fastened at the shoulder with a heavy, ornate clasp. They hold before their chest the cross of martyrdom, a symbol of their sacrifice and victory over death. In the northern of these cross-vaults, the figure of Saint George dominates, while in the southern we find the trio of Saints Unconquered, Vincent, and Saint Arethas, the martyr we are concerned with here. The placement of Saint Arethas in the Monastery of Hosios Loukas, alongside other significant martyrs, underscores the honor attributed to these defenders of the faith.

Artistic Analysis of the Fresco of Saint Arethas

Let us pause for a moment in front of the image of Saint Arethas, as presented to us by the unknown artist of the 11th century. The figure emerges from a circular medallion (chest piece), framed by concentric circles and intricate floral patterns that fill the remaining space of the cross-vault. Seeing this image, even digitally, one feels an immediate connection to the past, a sense of the sacred that the artist sought to convey.

Saint Arethas is depicted strictly frontal, his gaze intense and penetrating, looking beyond the viewer, towards the divine. The features of his face, although somewhat stylized according to the Byzantine Art of the time (Cormack), exude seriousness and spirituality. His hair and beard are rendered with fine, parallel lines, creating a sense of texture. He wears a light-colored tunic, decorated with the paragaudion on the shoulder, and over it a dark chlamys, fastened with a circular clasp. His right hand is extended holding a cross, while his left hand is covered by the chlamys. The use of earthy colors (ochre, brown) for the face and hair, contrasted with the dark blue or black of the chlamys and the green of the background with orange/red floral patterns, creates a balanced color palette. The halo, in golden ochre with a double outline, emphasizes the sanctity of the figure.

Imagine the 11th-century pilgrim entering the crypt, perhaps with the dim light of candles flickering, and encountering this figure on the ceiling. The frontal nature and intense gaze would create a sense of immediate communication, spiritual connection. The quality of the fresco, with its clean lines and decorative detail, would underscore the significance of the space and the depicted figures. (Perhaps a prompt for further exploration: Byzantine iconography of military saints).

Dating and Significance

The presence of specific holy fathers in another cross-vault, in the southeast, provides crucial evidence for dating the entire fresco decoration of the crypt. There, the Holy Ones Luke (the founder of the monastery), Philotheus, Athanasius, and Theodosius are depicted, with the inscription “The holy father of us” clarifying that they are deceased abbots of the monastery, and not merely the namesake saints (who are depicted elsewhere). Theodosius, known as Theodore Leovachus, was a prominent figure, an imperial official from a powerful Theban family, and the abbot of the monastery in 1048. He is considered a likely patron for the splendid mosaics of the katholikon (Stikas). His depiction as a holy father means that the frescoes of the crypt were made after his death, dating them close to the mid-11th century, perhaps during the abbacy of Gregory, who completed the marble revetment of the church. This makes the depiction of Saint Arethas and the other saints an important document of Middle Byzantine painting.

The face of Saint Arethas exudes Byzantine spirituality, with large eyes and a stern expression, characteristics of the art in the Monastery of Hosios Loukas.

Different Interpretations & Critical Assessment

Although the general dating of the frescoes in the crypt of Hosios Loukas to the mid-11th century is widely accepted, there are academic discussions on specific issues. Some researchers, such as Robin Cormack, focus on the broader artistic production of the period and the possible influences from workshops in Constantinople. Others, like Eustathios Stikas, have delved into the architectural history of the monastery, correlating the phases of decoration with specific periods of abbacy and patronage. There are also views that place the Byzantine mosaics and frescoes slightly later in the 11th century (Balty). These different approaches enrich our understanding, highlighting the complexity of studying such an important monument.

Indeed, the fresco representing Saint Arethas, situated within the Monastery of Hosios Loukas, transcends its function as a mere religious representation. It instead emerges as an invaluable conduit, offering profound insights into the intricate artistic craftsmanship, the nuanced theological thought, and the tangible historical realities that characterized Byzantium during the 11th century. Nestled within the expansive and meticulously curated fresco ensemble that adorns the crypt, the figure of the martyr engages in a profound, silent, and timeless dialogue that resonates both with the faithful who seek spiritual solace and the scholars who seek historical understanding. Its austere beauty, the palpable spirituality it exudes, and its undeniable historical significance collectively establish it as an indispensable component of the rich cultural heritage that the Monastery of Hosios Loukas so diligently preserves. This preservation, in a way, mirrors the preservation of historical narratives that the USA holds dear, where the stories of the past shape the present. The continued study of this fresco, along with the entirety of the iconographic program, continues to provide invaluable knowledge and inspire enduring admiration for the remarkable resilience of both faith and art throughout the ages.

Artistic Craftsmanship and Historical Realities

The fresco of Saint Arethas, in its detailed execution, reveals the profound artistic skill of the Byzantine era, a skill that allowed for the nuanced depiction of theological narratives. The inherent spiritual aura emanating from the artwork serves as a testament to the deep-seated faith that permeated Byzantine society, a faith that found expression in the very walls of their sacred spaces.

Enduring Resilience of Faith and Art

The historical significance of Saint Arethas’ fresco lies not only in its artistic merit but also in its capacity to serve as a tangible link to a bygone era. Through its silent dialogue, it bridges the gap between the past and the present, offering contemporary observers a glimpse into the spiritual and cultural landscape of 11th-century Byzantium. The study of this iconographic program, much like the study of historical documents in the USA, ensures the preservation and understanding of cultural legacies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Saint Arethas depicted in the Monastery of Hosios Loukas?

Saint Arethas was a great martyr of Christianity who lived in the 6th century in the city of Najran in Arabia (present-day Yemen). He was martyred along with many other Christians during persecutions. His depiction in the Monastery of Hosios Loukas, alongside other military saints and martyrs, emphasizes the importance of martyrdom and steadfast faith for the Byzantine church and society of the 11th century.

Where exactly is the fresco of Saint Arethas located in the Monastery of Hosios Loukas?

The fresco of Saint Arethas is located in the crypt, beneath the main Katholikon of the Monastery of Hosios Loukas. Specifically, it adorns the southern of the three central cross-vaults of the ceiling, along the North-South axis. He is depicted in a medallion alongside Saints Unconquered and Vincent, as part of a broader group of martyrs and military saints that dominate this section of the crypt.

What characterizes the style of the fresco of Saint Arethas?

The fresco of Saint Arethas in the Monastery of Hosios Loukas follows the patterns of Middle Byzantine painting of the 11th century. It is characterized by frontality, stylization of features, bold outline lines, and the use of earthy tones combined with more vibrant colors for decorative elements. The expression is serious and spiritual, aiming to highlight sanctity rather than realism.

Why are the frescoes in the crypt of Hosios Loukas important?

The frescoes of the crypt, including that of Saint Arethas, are extremely important as they represent one of the best-preserved ensembles of Byzantine painting from the 11th century. They provide valuable information about iconography, artistic style, theological concepts of the time, as well as the history of the Monastery of Hosios Loukas itself, aiding in the dating and understanding of the monument.

When exactly were the frescoes of Saint Arethas and the other saints in the crypt created?

The frescoes of the crypt of the Monastery of Hosios Loukas, including the depiction of Saint Arethas, are dated with relative accuracy to the third quarter of the 11th century, that is, approximately between 1050 and 1075 AD. This dating is primarily based on the depiction of specific abbots of the monastery as holy ones, indicating that the frescoes were made after their deaths.