Classical Attic red-figure vase painting of Helios with his four-horse chariot. The winged horses and the solar crown depict the cosmological transition from night to day. British Museum Collection, Beazley Archive No.5967.

The dramatic story of Phaethon is one of the most characteristic myths of ancient Greek mythology, offering both cosmological interpretations and moral lessons about hubris and its consequences. Phaethon, son of the god Helios and Clymene, sought confirmation of his divine lineage after being mocked by his peers. He approached his father, the god Helios, who, to prove his paternity, promised to fulfill any wish of his. The young Phaethon asked to drive the chariot of the Sun for one day. Despite his father’s warnings about the dangers, Phaethon insisted, resulting in a disastrous journey: he lost control of the horses, deviated from the set course, and caused chaos on earth, setting areas ablaze and creating deserts. Zeus was forced to intervene, striking Phaethon with a thunderbolt, causing him to fall into the river Eridanus.

The analysis of this myth provides valuable insights into the ancient Greek perception of cosmic order, divine authority, and human limits. The understanding of the various versions and interpretations of the myth was significantly aided by the study of ancient texts, such as Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” as well as comparative studies between different mythological traditions (search: ancient Greek cosmology).

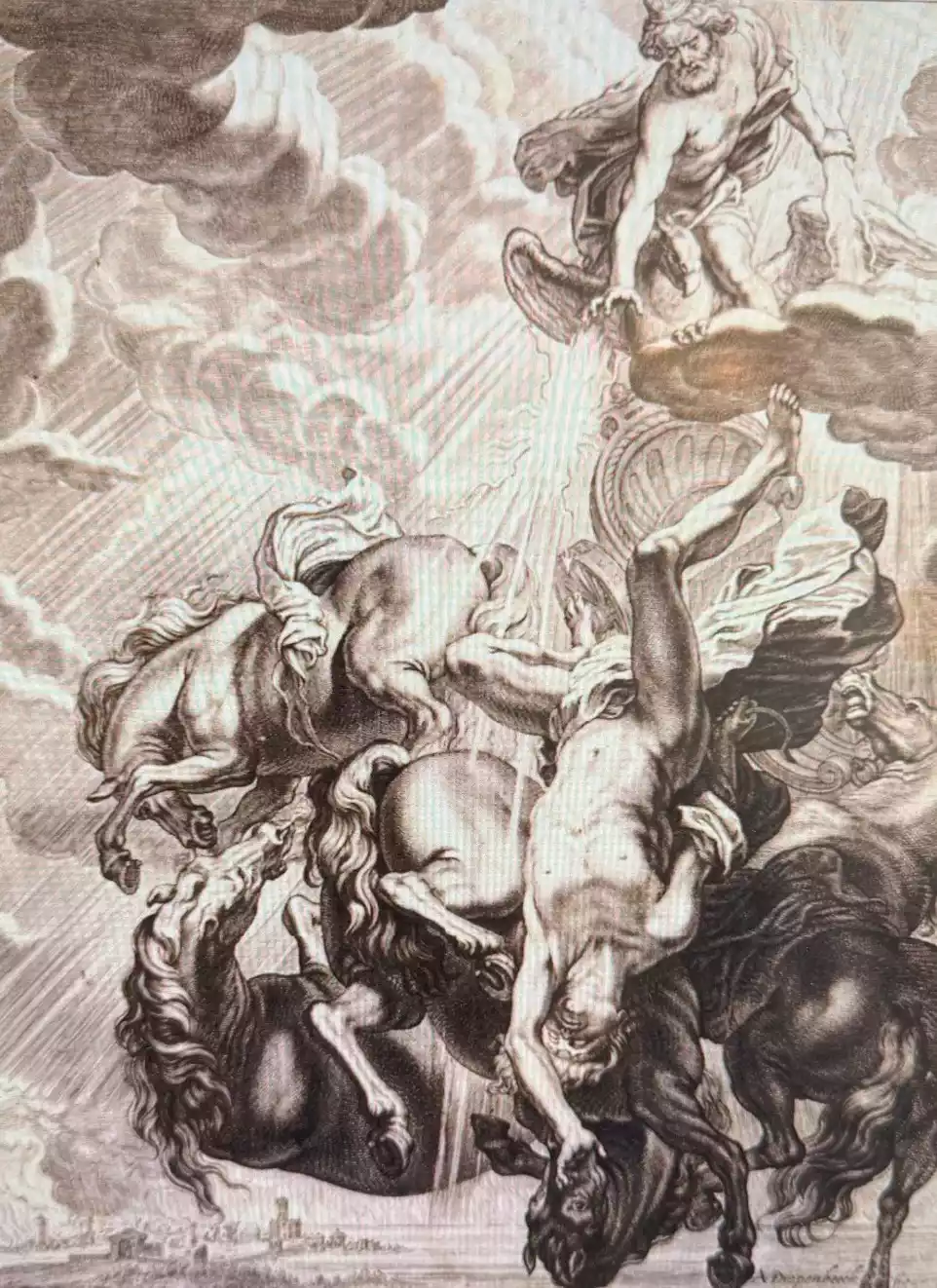

The iconographic depiction of Phaethon’s fall is an excellent example of the high engraving art of the 17th century. Cornelis Bloemaert, based on a design by Abraham van Diepenbeeck, composes a cosmological narrative.

The Origin and Youth of Phaethon

The Genealogy and Parents of Phaethon

The genealogical origin of Phaethon is a fundamental element for understanding the myth. According to the most prevalent version, Phaethon was the son of the god Helios (also known as Apollo in some traditions) and the nymph Clymene, daughter of Oceanus. Phaethon grew up away from his divine father, on earth, under the supervision of his mother. This hybrid origin — half god, half mortal — is a determining factor in the development of his tragic story (Synodinou).

The Questioning of Divine Origin

During his adolescence, Phaethon faced intense questioning about his origin from his peers. As described in Greek mythology, a peer insulted him by saying he was not the true son of the Sun. This insult drove Phaethon to seek confirmation of his identity, turning to his mother, who confirmed his divine origin and encouraged him to seek out his father (Decharme).

The Search for the Father at the Palace of the Sun

Determined to prove his origin, Phaethon embarked on a journey to the eastern edge of the world, where the brilliant palace of the Sun was located. The description of this fantastical journey and the magnificent palace with its golden columns and thrones adorned with precious stones is one of the most vivid elements of the myth. Ovid in his “Metamorphoses” offers the most detailed description of this meeting between father and son, thus rendering the myth of the solar chariot in its most poignant form (Jünger).

The Recognition and the Fateful Promise

During their meeting, the Sun immediately recognized his son and, to prove his paternity, gave him a solemn promise: he would fulfill any wish of his. Without hesitation, Phaethon asked to drive the chariot of the Sun for one day, wishing to demonstrate to his peers his divine origin. The Sun, realizing the danger, tried to dissuade his son from this endeavor, but bound by his oath, he was ultimately forced to relent. (Search for more information with the words: Ovid Metamorphoses Phaethon)

Preparations for the Fateful Journey

Before handing over the reins of the chariot to Phaethon, the Sun gave him detailed instructions for the dangerous route he had to follow in the sky. He warned him of the dangers of the extremes of the path — if he went too high, he would scorch the sky; if he went too low, he would set the earth on fire. He instructed him to follow the middle path, but the young Phaethon, carried away by arrogance and immaturity, did not pay the necessary attention to these crucial advices.

The scene depicts Phaethon near his father Apollo, at a moment foreshadowing the impending cosmic catastrophe. Work by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, circa 1731. Los Angeles Museum of Art Collection, M.86.257.

The Fateful Journey with the Chariot of the Sun

The Sun’s Promise and the Warnings

The story of Phaethon reaches its critical turning point when the god Helios, bound by his sacred promise, is forced to hand over the reins of his divine chariot to his immature son. The scene of the handover, as detailed in Ovid’s work, is a poignant moment of paternal anxiety and warnings. The Sun explains to his son the mysteries of the celestial path, the peculiarities of the stars and constellations, and above all, the deadly dangers the journey poses for an inexperienced driver. The tragedy begins to unfold from the moment Phaethon, with arrogance and naivety, ignores these crucial warnings (Lully).

The Destructive Course of the Solar Chariot

At dawn, the young Phaethon takes the reins of the fiery chariot, and immediately the disobedient horses sense the inadequacy of their driver. Deviating from the set course, the chariot follows a dangerous trajectory, at times coming too close to the earth, causing fires in forests and plains, and at other times moving towards the heights of the sky, threatening to disrupt the cosmic order. Phaethon’s inability to control the horses leads to disastrous consequences for the world: rivers dry up, mountains burn, and entire regions turn into deserts. Ovid’s description of this destruction is one of the most iconic depictions of Phaethon in classical literature (Wheeler).

The Intervention of Zeus and the Death of Phaethon

As the world burns and Gaia (Mother Earth) suffers, she appeals to Zeus, begging him to intervene to stop the destruction. The father of the gods, realizing the impending cosmic catastrophe, takes immediate action. He hurls a thunderbolt that strikes Phaethon and hurls him from the chariot. The unfortunate young man falls burning into the river Eridanus, marking the tragic end of his dangerous adventure. As vividly described in the work of Jean-Baptiste Lully, this fall (“chûte affreuse”) is the inevitable outcome of tragic hubris. (Search for more information with the words: tragic hubris ancient Greek mythology)

The Lament and Transformation of the Heliades

After Phaethon’s death, his sisters, the Heliades, mourn incessantly on the banks of the Eridanus. Their lament is so intense that they eventually transform into poplar trees, while their tears turn into amber, which continues to drip from the trees. This transformation is a characteristic example of the etiological nature of many Greek myths, offering a mythological explanation for natural phenomena and the origin of amber.

The Restoration of Cosmic Order by the Sun

The final episode of this tragic myth concerns the return of the Sun to his duties. Devastated by the loss of his son, the Sun initially refuses to continue his daily journey across the sky, plunging the world into darkness. Only after intervention by Zeus and the other gods does the Sun agree to return to his chariot, thus restoring cosmic order. This return symbolizes the inevitable continuation of the cosmic cycle, despite the personal tragedies even of the gods, underscoring a fundamental principle of Greek cosmology: the order of the universe transcends individual fate.

Phaethon, victim of his hubristic desire to drive the chariot of the Sun, is cast down amidst atmospheric disturbances and ethereal phenomena. Sunaert’s composition (1868) is part of the broader context of the reception of ancient myths.

The Symbolism and Impact of the Myth

Cosmological Interpretations of Phaethon’s Story

The narrative of Phaethon and the destructive driving of the solar chariot transcends mere mythological storytelling, offering rich ground for cosmological interpretations. In ancient Greek thought, this myth was often interpreted as an allegory of natural phenomena — specifically, “ecpyrosis,” a cosmic destruction by fire. This association is evident in philosophical analyses of the ancients, where the myth of Phaethon is treated as a metaphor for cosmic processes. Significant parallels are also found with the myth of Sushna in the Vedic tradition, where a similar case of earth’s burning is presented, suggesting possible intercultural influences in the evolution of this tragic narrative (Kitto).

Moral Lessons and the Concept of Hubris

The story of Phaethon contains fundamental moral lessons that resonate with the timeless value of the myth. A central concept is that of hubris — the arrogant self-confidence that leads to the transgression of natural limits and the provocation of divine order. Phaethon, despite warnings, insists on undertaking a task that far exceeds his abilities, inevitably leading to destruction. This motif — of punishment following arrogance — is repeated in many Greek myths and is a key element of Greek moral thought. (Search for more information with the words: hubris nemesis ancient Greek ethics)

The Myth of Phaethon in Art and Literature

The dramatic narrative of Phaethon has exerted a timeless influence on the arts and literature. From antiquity to the modern era, the image of the young man driving the chariot of the sun towards destruction has inspired numerous artistic creations. Particularly during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, the myth was a popular subject of painting, with iconic works by artists such as Rubens and Michelangelo. In literature, the story was excellently captured in Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” while in music, Jean-Baptiste Lully composed the tragedy “Phaëton” (1683), focusing on the hero’s tragic fall. The timeless popularity of the myth demonstrates its universal appeal and its ability to function as an allegory for ambition, arrogance, and the limits of human pursuit (Wheeler).

The masterful engraving by Hendrick Goltzius (1590) depicts the critical moment of Phaethon’s ascent to the celestial firmament, foreshadowing the impending cosmological destabilization.

Different Interpretations & Critical Assessment

The story of Phaethon has attracted different interpretative approaches among mythology scholars. Schmidt proposes an astronomical interpretation, linking the myth to meteorological phenomena, while Burkert places it within the tradition of initiation and coming-of-age myths. Vernant examines the myth as an expression of the boundaries between mortal and immortal, analyzing it as an archetypal conflict of human ambition with divine order. Kerényi recognizes elements of solar worship and primordial cosmological concepts in the narrative, while Dowden emphasizes its socio-political implications as a myth warning of the consequences of reckless governance. The multifaceted nature of the myth allows for this interpretative multiplicity, highlighting its timeless value.

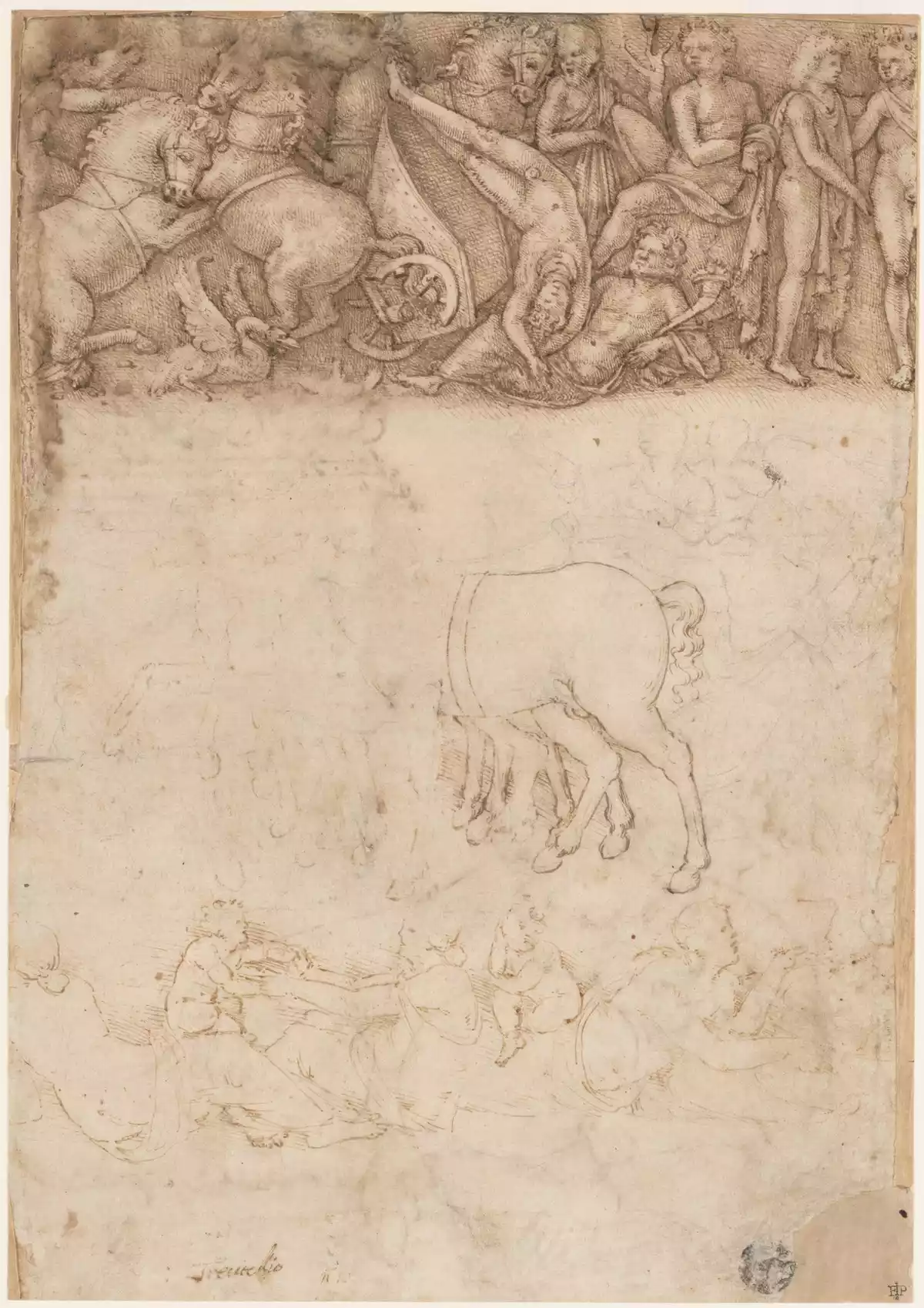

Study of Phaethon’s fall by Amico Aspertini (1474-1552), executed with black chalk and brown ink. It is a characteristic example of Renaissance study of ancient myths.

Epilogue

The myth of Phaethon and the chariot of the Sun remains one of the most compelling and timeless narratives of ancient Greek mythology. It reflects deep concerns about the nature of human ambition, the limits of our capabilities, and the consequences of arrogance. The tragic course of the young hero offers timeless lessons on the balance between daring and prudence, between ambition and self-awareness.

At the same time, the myth serves as a symbol of the search for identity, as Phaethon seeks to confirm his lineage and gain his father’s recognition. This multi-layered narrative continues to inspire art, literature, and philosophical thought, offering an archetype that resonates in every era and culture.

The distinct artistic composition by Pierre Brébiette presents the ambiguous conclusion of the myth of Phaethon. The depiction of the transformation of the Heliades reveals the subtle fusion of the myth with the natural world. Department of Graphic Arts of the Louvre.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was Phaethon’s origin in Greek mythology?

Phaethon was the son of the god Helios (Apollo in some versions) and Clymene, daughter of Oceanus. His dual nature as the offspring of a god and a mortal defined the course of his story, as his hybrid identity placed him in a dangerous boundary between the two worlds. The questioning of this divine origin by his peers was the trigger for the events that led to his tragic end.

Why did Phaethon want to drive the solar chariot?

The young Phaethon sought to drive the chariot of the Sun primarily to prove his divine origin to his peers who mocked him. Additionally, this endeavor represented an opportunity to fulfill an act of initiation, taking on his father’s task and thus confirming his place in the world of the gods. His desire reflected both personal ambition and the quest for identity and recognition.

What were the consequences of Phaethon’s driving of the Sun’s chariot?

Phaethon’s uncontrolled journey with the chariot of the Sun caused catastrophic consequences on earth. When the chariot came too close to the planet, it caused widespread fires, turning fertile areas into deserts (such as the Sahara, according to one interpretation), drying up rivers, and burning mountains. Conversely, when it moved too far away, it caused frost. This ecological disaster threatened the very existence of life on earth.

How is the myth of Phaethon symbolically interpreted by scholars?

The myth of Phaethon and the solar chariot is symbolically interpreted on multiple levels. Cosmologically, it represents natural phenomena such as unusual heat or solar flares. Morally, it symbolizes hubris and the consequences of exceeding human limits. Psychologically, it expresses unmediated ambition and the desire for recognition. These different approaches highlight the multifaceted character of this ancient narrative.

How did the myth of Phaethon influence art and literature?

The dramatic story of Phaethon has exerted a tremendous influence on art and literature over time. In antiquity, Ovid provided the most detailed account in his “Metamorphoses.” During the Renaissance, painters like Michelangelo and Rubens created impressive depictions of the young man’s fall. In music, Lully composed an entire tragedy, while in modern literature, the myth continues to inspire works that explore the limits of human ambition.

Bibliography

- Decharme, P. (2015). Mythology of Ancient Greece. Page 244.

- Jünger, H-D. (1993). Mnemosyne und die Musen: vom Sein des Erinnerns bei Hölderlin. Page 107.

- Kitto, H. D. F. (2024). Ancient Greek Tragedy.

- Lully, J-B. (1683). Phaëton: tragédie. Page 275.

- Synodinou, R. (2012). The Chariot of the Sun.

- Wheeler, S. M. (2000). Narrative Dynamics in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. p. 28.