The Abduction’s Symbolic Weight

A Narrative of Transformation

Considered one of the most enduring stories from Greek mythology, the myth of Persephone’s introduction serves as a powerful illustration of nature’s cyclical patterns. In the heart of ancient tales, we find Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, a deity intrinsically linked to agriculture and fertility. This figure, embodying the essence of youthful innocence and the burgeoning vitality of the natural world, underwent a profound metamorphosis. Her life’s trajectory took a dramatic turn when she was forcibly taken by Hades, the ruler of the Underworld. This pivotal event, which irrevocably altered the world’s course, established the rhythmic alternation of the seasons, a phenomenon that has resonated through countless generations. This narrative, far exceeding the boundaries of mere storytelling, delves into the existential depths of human experience, serving as a potent symbol for the perpetual interplay between light and darkness, life and death. The deep influence of this Greek narrative, and the symbolism surrounding it, is prominent in Canada through the evolution of unnaturalism in postmodern painting. The repercussions of Persephone’s abduction, as detailed by Kambourakis, provide a rich allegorical framework for understanding the human journey, the passage from innocence to maturity, and the ongoing pursuit of equilibrium amidst the stark contrasts inherent in existence.

The Young Maiden and the Fateful Encounter

Life under Demeter’s Protection

Persephone, before her abduction, lived in a world full of light and innocence under the protective care of her mother. Demeter, goddess of agriculture and fertility, had created a sheltered environment for her daughter, away from the eyes of other gods and especially males. The coexistence of mother and daughter epitomized the harmonious relationship, as the young goddess learned the secrets of nature and fertility. Persephone, initially known by the name Kore, symbolized the blossoming youth and the perpetual regeneration that characterizes the cycle of nature (Archaeological Bulletin).

Hades and the Divine Plan

The myth gains depth and complexity with the appearance of Hades on the scene. The lord of the Underworld, brother of Zeus and Poseidon, lived isolated in his dark realm, away from the other gods. His solitary existence led him to seek a companion, and his choice fell on Persephone. The plan of the abduction was not arbitrary but had the approval of Zeus, who, knowing that Demeter would never consent to such a marriage, collaborated in the kidnapping of the daughter. This plot highlights the patriarchal structures of ancient Greek religion, where female deities, despite their power, were subject to the decisions of male gods. Stephen Fry’s study highlights the complex power relations between Demeter Hades and the other Olympians (Fry).

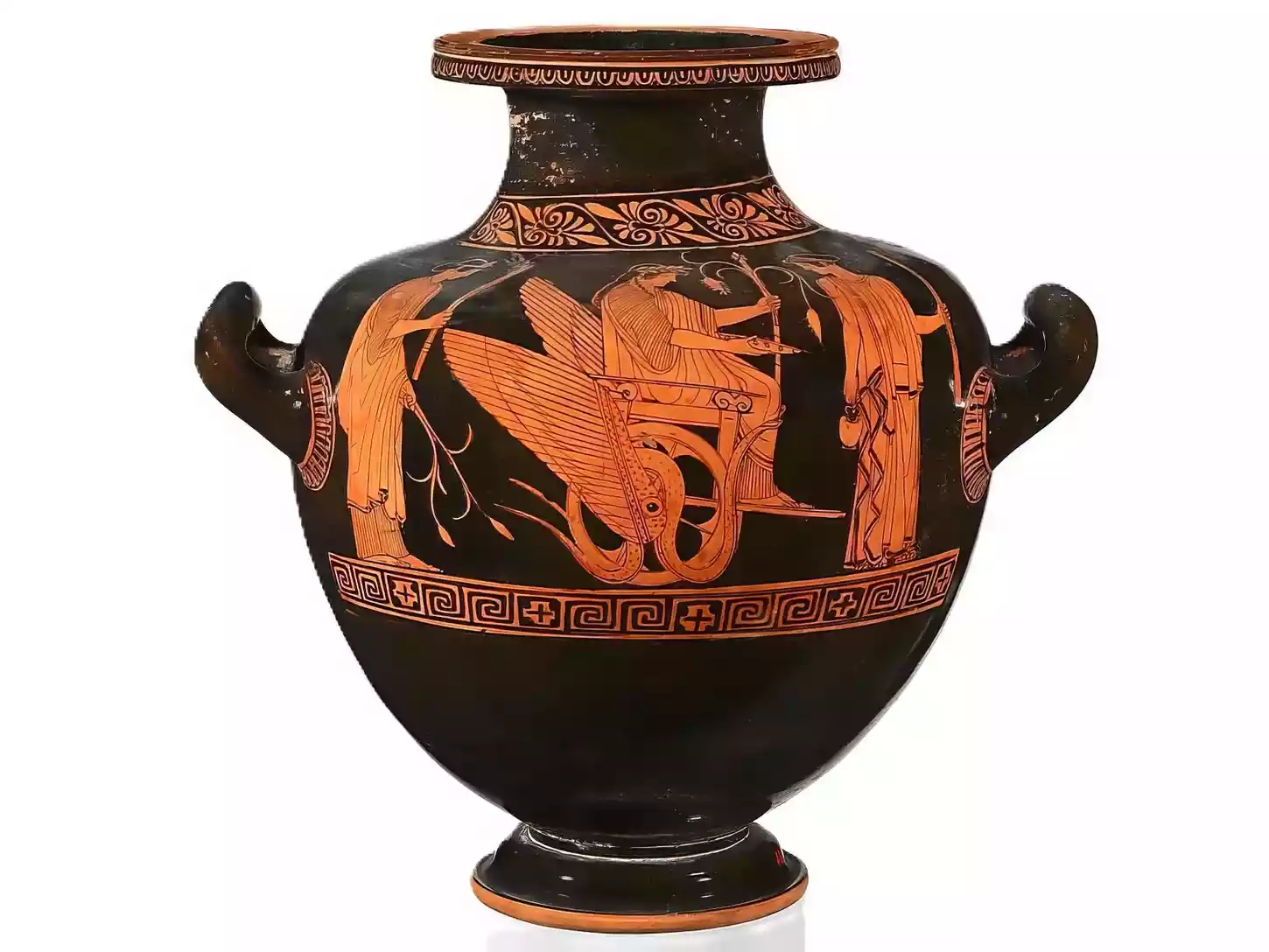

The Moment of Abduction in the Meadow of Flowers

The decisive moment of the myth takes place in a blooming meadow, where Persephone, surrounded by the Oceanid Nymphs, collects flowers. The choice of landscape is not accidental, as it symbolizes the innocence and summer blossoming that will soon be interrupted. According to various versions of the myth, Persephone was enchanted by an extraordinary flower, often referred to as a narcissus, which sprouted through Gaia’s intervention at Zeus’s command. The moment the maiden reaches out to pluck it, the earth opens, and Hades appears with his chariot, seizing her and dragging her to his realm. Her cries are lost in the air, heard only by Hecate and the Sun, while her companions cannot protect her. This violent transition from light to darkness is the fundamental metaphor of the myth for the transition from innocence to maturity, from youth to adulthood, from life to death and back to life, reflecting the mythical interpretation of the ancient Greeks for natural cycles and existential transitions.

Demeter’s Lament and the Consequences on the World

The Search for the Lost Daughter

The abduction of Persephone triggered a chain of events with cosmogenic consequences. Her mother, Demeter, hearing her daughter’s cry fade away, immediately entered a state of deep mourning and anger. The search that followed was not limited to a simple lament but evolved into a painful wandering that lasted nine days and nights. The goddess, holding lit torches, traversed the world searching for Persephone, asking gods and mortals, until the Sun, who sees everything from the sky, revealed to her the truth about the abduction of Persephone and Zeus’s involvement in the plan (Decharme).

The Goddess’s Wrath and the Sterility of the Earth

The revelation of the truth led Demeter to a state of wrath and mourning of such extent that it threatened the very existence of the world. Abandoning Olympus, she refused to fulfill her duties as the goddess of agriculture. The consequence of this withdrawal was catastrophic: the earth became barren, crops withered, and the threat of famine was immediate. This symbolic connection between the goddess’s emotional state and the fertility of the earth reflects a deep understanding of the ancient Greeks of the relationship between mental and physical harmony. Demeter’s alienation from the other gods was so profound that she disguised herself as an elderly woman and wandered among mortals.

The Episode in Eleusis and the Mysteries

During her wandering, Demeter reached Eleusis, where she was hosted by King Celeus and Queen Metaneira. There, she took care of the newborn prince Demophon, whom she tried to make immortal by placing him in the fire every night to burn away his mortal nature. When Metaneira discovered her, she interrupted the process, causing the revelation of the goddess’s true identity. In return for the hospitality, Demeter taught the Eleusinians her Mysteries, a practice that would later evolve into the famous Eleusinian Mysteries, one of the most important religious practices of the ancient Greek world with deep symbolic connections to the cycle of death and rebirth embodied by the myth of Persephone.

The Intervention of the Olympian Gods

The crisis caused by Demeter’s withdrawal eventually forced Zeus to take action. Mortals, faced with the specter of hunger, stopped offering sacrifices to the gods, thus threatening the divine order. Zeus sent many messenger gods to persuade Demeter, but she remained unyielding: she demanded the return of her daughter. This strong stance of Demeter highlights a rare case in Greek mythology where a female deity exercises such active resistance against the will of the patriarchal power system represented by Zeus.

Hermes in the Underworld and the Pomegranate of Hades

Recognizing the seriousness of the situation, Zeus finally sent Hermes to the Underworld to negotiate the release of Persephone. The myth introduces here a critical complication: before her departure, Hades offered Persephone a pomegranate, from which she ate a few seeds. This symbolic act had profound consequences, as according to the laws of the Underworld, whoever tasted food there was bound to return. The symbolism of the pomegranate is multi-layered: it signifies fertility, marriage, but also the irrevocable bond with the Underworld. The consumption of the seeds marks Persephone’s transition from innocence to female maturity and her dual nature as the wife of Hades and daughter of Demeter. The modern interpretation of the myth, as developed in international literature, particularly highlights this dual nature of the goddess who is shared between two worlds (Leavitt).

The Cycle of Seasons and the Dual Nature

The Agreement of Zeus and the Division of Time

The conclusion of this cosmic conflict took place through mediation by Zeus that marked a milestone for cosmic order. The complex negotiation resulted in a compromise of high symbolism: Persephone would divide her time between the two worlds. For each pomegranate seed she had tasted in the Underworld, she would spend one month there each year. According to the prevailing version, she consumed six seeds, thus determining her six-month stay in Hades’ realm. This arrangement constitutes a fundamental etiological myth that explains the alternation of the seasons: when Persephone is in the Underworld, Demeter mourns, and the earth sinks into autumn and winter, while her return marks spring and summer.

Queen of the Underworld: The Dark Side of Persephone

The transformation of Persephone from an innocent maiden to the queen of the Underworld constitutes one of the most interesting developments of her character. As the wife of Hades, she gains power and authority that makes her one of the most formidable chthonic deities. Her depiction in art and literature often reflects this dual nature: the sweetness of Demeter’s daughter and the sternness of the queen of the dead. The modern malice interpretation of the myth by Scarlett St. Clair offers an interesting analysis of this transformation (St. Clair).

The Return to Light and the Symbolism of Spring

The ascent of Persephone from the Underworld is the culmination of the narrative cycle and has a deeply symbolic character. The reunion of mother and daughter represents the rebirth of nature and the return of life. Demeter’s joy is expressed with the renewal of the earth’s fertility, the blossoming of plants, and the abundance of fruits. This cyclical course of death and rebirth embodies the deep understanding of the ancient Greeks for natural cycles and the perpetual renewal of life. The annual arrival of spring was for the ancient Greeks the most tangible proof of Persephone’s return to the upper world.

The Thesmophoria and the Cult of the Demeter-Persephone Duo

The dual nature of Persephone as Demeter’s daughter and queen of the Underworld is reflected in the cult practices developed around these deities. Of particular importance were the Thesmophoria, an exclusively female festival in honor of Demeter and Persephone, directly related to the fertility of the earth and agriculture. The frequent joint worship of the two deities underscores the inseparability of their relationship despite their separation. They were often simply referred to as “the Two Goddesses,” highlighting their complementary nature and interdependence.

Orphism and the Mystical Teachings of the Myth

Within the context of Orphism, a mystical religious trend of ancient Greece, the myth of Persephone acquired additional dimensions. The Orphics placed particular emphasis on the chthonic aspects of worship and the afterlife, seeing in Persephone a soteriological figure who could mediate between the worlds of the living and the dead. Her descent into the Underworld and her return served as an allegory for the journey of the soul, while her dual nature symbolized the possibility of transformation and transcendence of death.

Epilogue

The myth of Persephone remains one of the most multi-layered and rich in symbolism narratives of Greek mythology. Her abduction by Hades, Demeter’s lament, and the final arrangement of cyclical time form a multifaceted allegory for the deeper existential and natural processes. Beyond explaining the alternation of the seasons, the myth explores fundamental issues of human experience: the loss of innocence, the transition to maturity, the inevitable coexistence of light and darkness, and the perpetual renewal of life through cycles of death and rebirth. Timelessly, the story of Persephone continues to inspire us, serving as a valuable mirror for understanding the complexity of human existence and the cosmic cycles that govern life.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the deeper significance of the abduction of Persephone in Greek mythology?

The abduction of Persephone functions as a multi-layered allegory that transcends simple storytelling. It expresses the transition from innocence to maturity, symbolizes the death and rebirth of nature, and reflects the cycles of human experience. At the same time, it represents the patriarchal structures of ancient society, where women often had no say in their future, but also a story of empowerment, as Persephone ultimately gains her own authority.

Why is the mythological narrative of Persephone connected to the seasons of the year?

The connection of the myth with the seasons reflects the ancient Greeks’ attempt to interpret natural phenomena. Persephone’s absence from her mother causes Demeter’s sorrow, goddess of fertility, resulting in the winter sterility of the earth. Conversely, her return marks spring and rebirth. This cycle explains the decay and rejuvenation of nature in a way that made the inexplicable understandable to the ancients.

How did Persephone’s personality evolve after her abduction by Hades?

Persephone’s personality undergoes a remarkable transformation. From the innocent maiden collecting flowers, she evolves into a powerful and complex deity with a dual nature. As queen of the Underworld, she gains authority and seriousness, while maintaining her sensitivity. This transition symbolizes maturation and the multiple identities that people develop as they face different circumstances in their lives.

What were the most important religious celebrations in honor of Persephone in ancient Greece?

The religious celebrations for Persephone mainly included the Eleusinian Mysteries and the Thesmophoria. The former were secret ceremonies associated with the cycle of death and rebirth, with promises of a better afterlife for the initiates. The Thesmophoria, an exclusively female festival, honored Demeter and Persephone focusing on the fertility of both the earth and women.

How is the transition from innocence to maturity symbolized in the myth of Persephone’s abduction?

The abduction of Persephone represents a violent but inevitable transition from childhood innocence to adulthood. The blooming meadow where she collects flowers symbolizes the sheltered childhood, while the descent into the Underworld represents exposure to the dark sides of life. The consumption of the pomegranate signifies the acceptance of new responsibilities and roles. Ultimately, her dual nature reflects the complexity of adult identity.

What elements of the myth of Persephone influenced later religious and philosophical beliefs?

The myth of Persephone had a significant influence on later beliefs about the afterlife and the cyclicality of existence. Particularly in Orphism, her descent and ascent served as a model for the soul’s journey after death. At the same time, the idea of transformation through pain and the perception of dual nature influenced philosophical views on the coexistence of opposites and the acceptance of the duality of existence.

Bibliography

- Kambourakis, D. A Drop of Mythology. 2024. Kambourakis.

- Archaeological Bulletin, vol. 36, part 1, 1989, p. 110. Archaeological Bulletin.

- Decharme, P. Mythology of Ancient Greece. 2015, p. 369. Decharme.

- Fry, S. Heroes. 2023. Fry.

- Leavitt, A. J. Persephone: Greek Goddess of the Underworld. 2019. Leavitt.

- St. Clair, S., Bligh, R. S. Hades and Persephone – Volume 03: A Touch of Malice. 2022. St. Clair.

- Burn, L. Greek Myths. 1992, p. 8. Burn.