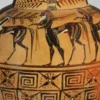

Orestes is one of the most enigmatic and psychologically complex tragic figures of ancient Greek mythology and drama. Son of King Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, Orestes found himself at the center of a family tragedy that marked the house of Atreus. His story revolves around the revenge he undertakes for the murder of his father by his mother and her lover Aegisthus, leading to the tragic act of matricide. The figure of Orestes inspired the three great tragic poets – Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides – who approached his character and moral conflicts from different perspectives, reflecting the philosophical and social quests of their time. The presentation of Orestes in ancient tragedy examines fundamental issues of justice, moral duty, divine intervention, and mental anguish. The transition from the archaic notion of personal revenge to institutionalized justice is excellently depicted in the evolution of Orestes’ myth, especially in Aeschylus’ trilogy “Oresteia.” The timeless significance of Orestes’ figure lies in his ability to embody timeless dilemmas of human existence and offer a prism through which issues of moral responsibility, mental disorder, and social justice are examined.

The Myth of Orestes and His Origin

The House of Atreus and the Curse of the House

The house of Atreus, one of the most prominent genealogical lines of ancient Greek mythology, is distinguished by the tragic curse that follows it through time, leading to a sequence of bloody events unfolding over generations. This genealogical origin of Orestes begins with Tantalus, who committed the hubris of testing the gods by offering them his dismembered son Pelops as a meal. Pelops, after being resurrected by the gods, became king of the Peloponnese and father of Atreus and Thyestes, between whom a deep enmity developed, leading Atreus to take revenge on his brother by serving him his children as a meal.

Agamemnon, father of Orestes, inherited this burdensome past and was forced to offer his daughter Iphigenia as a sacrifice to secure favorable winds for the Achaean fleet heading to Troy. This act ignited the hatred of his wife Clytemnestra, who, in collaboration with her lover Aegisthus (son of Thyestes), murdered Agamemnon when he returned from the Trojan War. According to recent research approaches, the curse of the Atreids is a symbolic depiction of the social and political transformations of the archaic period, where the transition from personal law of revenge to institutionalized justice is depicted through mythical narration (Kotsia).

The Chronicle of Matricide and Orestes’ Motives

The young Orestes was removed from Mycenae for his protection after Agamemnon’s murder, finding refuge in Phocis where he was raised by King Strophius. There, a strong friendship developed between Orestes and Pylades, son of Strophius, which would play a decisive role in subsequent events. Apollo, through the oracle of Delphi, gave Orestes the divine command to avenge his father’s murderers, thus placing him before a relentless moral dilemma: to honor his father’s memory but commit the heinous crime of matricide or to ignore the divine command.

Orestes’ return to Mycenae, disguised and accompanied by Pylades, marks the climax of the tragic narrative. After meeting his sister Electra, who was mourning at Agamemnon’s grave, Orestes proceeds with the execution of revenge, first killing Aegisthus and then his mother. As Mikropoulou points out in her extensive study on Euripides’ influence on post-classical tragedy, Orestes’ motives vary significantly in the different dramatic approaches of the three tragic poets, reflecting the changing social and philosophical perceptions of their time.

Orestes in Ancient Tragedy

Aeschylus’ “Oresteia”: From Revenge to Justice

Aeschylus’ trilogy “Oresteia” (458 BC), consisting of the plays “Agamemnon,” “The Libation Bearers,” and “The Eumenides,” constitutes the most comprehensive dramatic treatment of Orestes’ myth and presents an exceptionally insightful analysis of the transition from the archaic system of personal revenge to institutionalized justice. In “The Libation Bearers,” Orestes appears as the instrument of Apollo’s divine will, undertaking the obligation to avenge his father’s murder. The act of matricide is presented as an imperative necessity, fitting within the framework of the traditional moral code that demands the punishment of the father’s murderers.

However, in “The Eumenides,” Aeschylus extends his reflection beyond Orestes’ personal tragedy, introducing an innovative dimension: the establishment of the Areopagus court by Athena for the trial of the matricide. In this extremely important work of ancient tragedy, Yosi points out that Orestes’ physical and mental state is depicted with exceptional accuracy in the expression “ὦ σῶμ’ἀτίμως κἀθέως ἐφθαρμένον,” indicating the protagonist’s complete disintegration after committing matricide.

Euripides’ Orestes: Mental Illness and Hallucinations

Euripides, in the eponymous tragedy “Orestes” (408 BC), presents a radically different approach to the character, focusing on the psychological dimension of his experience after matricide. Unlike Aeschylus, Euripides moves away from the theological framework and examines the psychopathological manifestations that plague the protagonist. Delios, in his medical interpretation of Orestes’ hallucinations, thoroughly analyzes how the tragic hero is portrayed as suffering from intense hallucinations and symptoms resembling modern diagnoses of psychiatric disorders.

Euripides depicts Orestes bedridden, tormented by acute fits of mania during which he envisions the Furies pursuing him. His sister Electra is presented as a steady presence by his side, caring for him during this mental and physical collapse. Orestes’ emotional and psychological state is analyzed with exceptional detail, creating a portrait of human suffering that transcends the conventional frameworks of ancient tragedy and foreshadows modern psychological approaches.

The Timelessness of Orestes: From Ancient Tragedy to Modern Self-Exploration

The figure of Orestes remains timelessly relevant, as he embodies fundamental dilemmas of human existence. His journey from revenge to catharsis is a symbolic depiction of the moral and psychological path to self-awareness. The handling of the act of matricide and its subsequent consequences highlight the conflict between personal ethics and social imperatives, while his final vindication, especially in Aeschylus’ “Oresteia,” marks the transition from an archaic justice system to a more advanced institutional framework. The multi-layered approach of the tragic poets to Orestes’ character reflects the different perceptions of moral responsibility, the role of the gods, and mental anguish, making him one of the most complex and timelessly relevant mythical heroes.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main difference between Aeschylus’ Orestes and Euripides’ Orestes?

Aeschylus’ Orestes is primarily presented as an instrument of divine will, acting on Apollo’s command to restore justice for his father’s murder. In contrast, Euripides’ Orestes is a deep psychological study of a traumatized man suffering from the consequences of his actions, with an emphasis on the hallucinations and mental illness that plague him after matricide, reflecting a shift in focus from the theological to the anthropocentric framework.

How is the curse of the Atreids connected to Orestes’ tragic fate?

The curse of the Atreids, which began with Tantalus’ hubris and continued with the bloody acts of Atreus and Thyestes, creates a dead-end framework in which Orestes is called to act. Regardless of his choice – whether to respect his mother or avenge his father – Orestes is doomed by the genealogical curse to face tragic consequences, highlighting the conflict between archaic codes of honor and the new moral perceptions of the classical period.

Why are Orestes’ hallucinations a central element in Euripides’ tragedy?

Orestes’ hallucinations are an innovative element with which Euripides explores the mental dimension of guilt and the internal conflicts caused by the violation of the strongest social taboos. By depicting Orestes tormented by the Furies, Euripides transfers the external punishment of traditional mythology into an internalized psychological state, foreshadowing modern concepts of conscience and mental illness associated with traumatic experiences.

What is Pylades’ role in Orestes’ story?

Pylades serves as a moral support and loyal ally to Orestes in his tragic journey. While in Aeschylus he remains more in the background, in Euripides he gains a more substantial role, reinforcing Orestes’ determination and actively participating in the revenge plan. Their unbreakable friendship is a constant point of reference in the various versions of Orestes’ myth, highlighting the importance of loyalty and solidarity amid tragic circumstances.

How is Orestes’ figure treated in modern literature and theatrical tradition?

Orestes’ complex personality has been a source of inspiration for modern writers and playwrights who adapt the myth to explore contemporary issues such as post-traumatic disorder, mental health, and moral conflicts. From Sartre and O’Neill to contemporary playwrights, Orestes remains a symbol of a man facing relentless moral dilemmas, highlighting the timelessness of the tragic conflicts that run through human existence.

What is the significance of the Areopagus in Orestes’ final judgment?

Orestes’ trial in the Areopagus, as presented in Aeschylus’ “The Eumenides,” symbolizes the transition from the archaic notion of personal revenge to institutionalized justice. By establishing a court with human judges, Athena introduces an innovative approach to the administration of justice, where judgment is not left to divine forces but to human judgment and social institutions, marking a fundamental evolutionary moment in the course of ancient Greek civilization.

Bibliography

- Yosi M. (2017). “ὦ σῶμ’ἀτίμως κἀθέως ἐφθαρμένον”. Extreme expressions of the body in ancient tragedy. Skene.

- Kotsia V. (2019). The Role of the Gods in Ancient Greek Tragedy: the cases of Aeschylus’ “Agamemnon,” Sophocles’ “Electra,” and Euripides’ “Iphigenia in Aulis.” Amitos.

- Mikropoulou A. (2024). Euripides’ Influence on Post-Classical Tragedy: Shakespeare and His Successors. Amitos.

- Delios G. (2023). Orestes’ Hallucinations in Euripides’ Eponymous Tragedy and Their Medical Interpretation. Postgraduate Student Conference.