Odysseus tied to the mast of the ship listens to the song of the Sirens. Attic red-figure amphora, circa 480-470 BC. British Museum, catalog number GR 1843.11-3.31.

The Odyssey, the second great epic attributed to Homer, narrates the long and tumultuous effort of the king of Ithaca, Odysseus, to return to his homeland after the end of the Trojan War. In contrast to the Iliad, which focuses on war exploits and battle, the Odyssey presents a different aspect of heroism – that of perseverance, ingenuity, and mental endurance. Odysseus, known for his intelligence and resourceful nature, faces countless trials in his attempt to reach his beloved Ithaca, where his faithful wife Penelope and his son Telemachus await him. This epic is not merely the narration of an adventure but a deeply allegorical account of the human condition, the trials of life, and the eternal quest for nostos – the return to home and familial warmth.

The Odyssey has profoundly influenced global culture and literature, making its protagonist a symbol of human wandering and quest. The adventures of Odysseus – from his encounter with the Cyclops Polyphemus to facing the Sirens and his descent into Hades – are an integral part of the Homeric tradition that has shaped Greek and world literature. The hero’s journey back to Ithaca has become a timeless metaphor for the human search for identity, purpose, and familiar space, influencing artists and thinkers from antiquity to the present (Trypanis).

Odysseus in battle: Chalcidian black-figure amphora from Rhegium in Southern Italy, circa 540 BC. Work of the Inscription Painter. Dimensions: 39.6 × 24.9 cm.

The Beginning of the Journey: From Troy to Wandering

The Departure from Troy and the First Adventures

Odysseus’s adventure begins immediately after the fall of Troy, when the resourceful king and his companions set out for the return to their homeland. Their first stop is the land of the Cicones, where after a successful raid, Odysseus’s men stay longer than they should, resulting in an attack by Ciconian reinforcements and the loss of several companions. This episode sets the tone for the entire journey – recklessness and lack of restraint will prove fatal for the Ithacan group (Mantis).

The Wrath of Poseidon: The Cause of the Long Wandering

The defining moment that turns Odysseus’s journey into a long wandering is his conflict with the god Poseidon. The blinding of the Cyclops Polyphemus, son of Poseidon, provokes the wrath of the sea god, who vows to prevent the hero’s return to Ithaca. This divine wrath is the central obstacle that Odysseus must overcome, creating a dynamic confrontation between human intelligence and divine power. (Search for more information with the words: Poseidon Odysseus Hostility)

Odysseus’s Companions and Their Gradual Loss

One of the tragic aspects of the journey is the gradual loss of Odysseus’s companions. Of the original twelve ships that departed from Troy, only Odysseus’s ship manages to navigate the dangers of the sea. His companions are lost in various episodes, either due to their own mistakes, such as when they opened Aeolus’s bag of winds, or due to external dangers, as in the case of Scylla and Charybdis. Each loss increases the burden of responsibility that Odysseus bears as a leader and intensifies his loneliness on his journey.

Mind and Metis: Odysseus’s Weapons in the Battle with the Unknown

In contrast to the heroes of the Iliad, who are distinguished mainly for their physical strength, Odysseus stands out for his intelligence and inventiveness. His metis – intelligence and practical wisdom – is his main weapon against the challenges of the journey. From dealing with Polyphemus to escaping from Calypso, Odysseus uses his insight and adaptability to overcome obstacles that would be impossible to face with physical strength alone.

The Gods as Allies and Opponents in Odysseus’s Journey

Throughout the journey, the gods play a crucial role in Odysseus’s path. While Poseidon remains the main opponent, Athena stands steadfastly by the hero’s side, offering guidance and protection. Zeus, as the supreme judge, ultimately allows Odysseus’s return, recognizing his worth and perseverance. This divine dimension of the journey highlights the importance of divine favor in the ancient Greek world, but also the belief that man can, with his virtues, earn the esteem even of the immortals.

Nekyia scene: Odysseus converses with Tiresias in Hades. Lucanian red-figure calyx-krater by the Dolon Painter (circa 380 BC). BnF Museum.

Significant Stops on the Journey Back

The Encounter with the Cyclops Polyphemus

One of the most iconic moments of the Odyssey is Odysseus’s encounter with the Cyclops Polyphemus. This episode reveals both the intelligence and weaknesses of the protagonist. After being trapped in the cave of the monstrous giant, the resourceful Odysseus devises a trick – he introduces himself as “Nobody” and, after intoxicating the Cyclops, blinds him with a heated stake. When the other Cyclopes rush to help and ask who attacked him, Polyphemus replies “Nobody,” leading them to leave. However, at the pivotal moment of escape, Odysseus cannot contain his pride and reveals his identity, provoking Poseidon’s wrath and thus determining the course of his future wandering.

Circe and Calypso: The Divine Traps of Nostos

On the path of nostos, Odysseus encounters two powerful divine figures that threaten to thwart his return – the sorceress Circe and the nymph Calypso. Circe transforms his companions into pigs, but Odysseus, with Hermes’s help, manages to resist her spells and persuade her to restore his companions. They remain for a year on her island, where Circe eventually offers valuable advice for the rest of their journey. Calypso, on the other hand, holds Odysseus for seven years on her island Ogygia, offering him immortality and eternal youth. However, the hero, despite the divine offers, remains focused on his goal to return to his beloved Ithaca, proving the value of mortal human life and family bonds over immortality. (Search for more information with the words: Odysseus Calypso Immortality)

The Hospitality of the Phaeacians: The Last Stage before Ithaca

After his release from Calypso, Odysseus reaches the island of the Phaeacians, where for the first time he is treated with respect and genuine hospitality. There, in the court of King Alcinous, Odysseus narrates his adventures, revealing for the first time his identity and the entire story of his journey. The Phaeacians, impressed by his tales and recognizing his bravery and endurance, decide to help him return to his homeland, offering him a ship and valuable gifts. This hospitable reception marks the end of Odysseus’s sea wandering and the beginning of the final phase of his return – reclaiming his place in Ithaca.

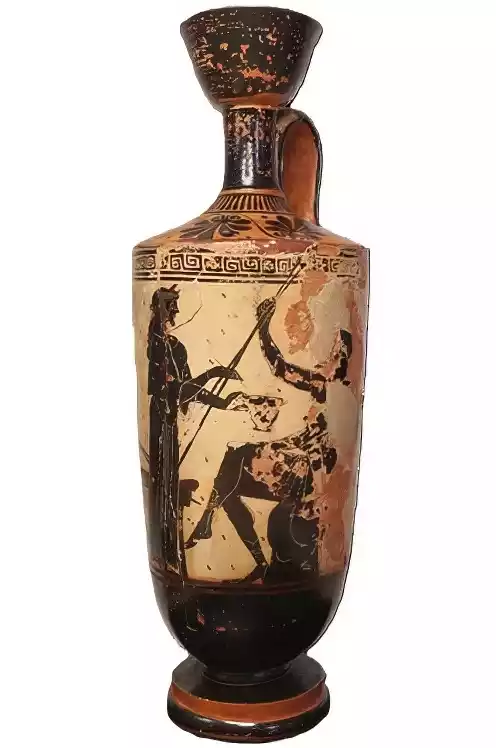

Attic black-figure lekythos (490-480 BC) from Eretria depicting the meeting of Odysseus with Circe. Exhibited at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, inv. no. A 1133.

The Return to Ithaca and Restoration

Odysseus as a Beggar: Recognition and the Suitors

Odysseus’s arrival in Ithaca marks the beginning of the final and perhaps most demanding stage of his adventure. The goddess Athena, protector of the hero throughout his journey, transforms him into an old beggar so that he is not recognized prematurely. This disguise allows him to observe and assess the situation in his palace, where the suitors have been abusing hospitality and his wealth for years, vying for the hand of his wife Penelope and the throne of Ithaca.

The Meeting with Eumaeus and Telemachus

Odysseus’s first contact with Ithaca is through his faithful swineherd Eumaeus, who, although he does not recognize his master, offers him excellent hospitality. Subsequently, Odysseus meets his son Telemachus, who was returning from his journey to Pylos and Sparta, where he was seeking information about his father’s fate. The recognition between father and son is one of the most moving moments of the epic, as Odysseus reveals his true identity to Telemachus, and the two plan the extermination of the suitors.

The Bow Contest and the Punishment of the Suitors

The climax of Odysseus’s return to Ithaca is the famous scene of the bow contest. Penelope, who remains faithful to her husband despite his long absence, announces to the suitors that she will marry whoever can shoot an arrow through twelve axe heads with Odysseus’s bow. The suitors, one by one, fail even to string the bow, while Odysseus, still disguised as a beggar, succeeds in the contest on his first attempt and immediately turns his arrows against the suitors. The ensuing slaughter of the suitors is one of the most dramatic scenes of the Odyssey, symbolizing the restoration of order and justice. (Search for more information with the words: Suitor Slaughter Odyssey Bow)

The Reunion with Penelope: The Completion of the Journey

After the extermination of the suitors, Odysseus faces the final test – recognition by his faithful wife Penelope. Despite her initial skepticism, Penelope sets one last test for the man claiming to be her husband – she asks him to move the marital bed, knowing that this is impossible as Odysseus had built it around the trunk of a living tree. Odysseus’s knowledge of this secret finally convinces Penelope of his identity, leading to the emotional reunion of the couple after twenty years of separation.

Reconciliation with Ithaca: Odysseus as King and Father

The Odyssey concludes with Odysseus’s restoration to the throne of Ithaca and reconciliation with his compatriots. The hero, having now returned to his normal form, visits his elderly father, Laertes, offering a touching moment of family reunion. At the same time, he faces the threat of revenge from the families of the suitors, a conflict resolved by the intervention of Athena and Zeus, who impose peace. Odysseus’s journey thus concludes with the restoration of harmony in his kingdom and his return to the role of king, husband, and father.

Clay plaque from Melos depicting the return of Odysseus to Penelope circa 460-450 BC. Dimensions: 18.7 x 27.8 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Different Interpretations & Critical Assessment

The Odyssey has been the subject of multifaceted interpretations by scholars from different academic approaches. Vernant examines Odysseus as an archetype of the transition from the heroic to the political man, while Benjamin analyzes nostos as an allegory of human self-awareness. Stan has approached the epic psychoanalytically, identifying in Odysseus’s wanderings the journey towards individual completion. In contrast, Finley focuses on the historicity of the text, seeking elements of Mycenaean and post-Mycenaean society. Newer scholars like Malkin and Dimock approach the epic through post-colonial and feminist perspectives, highlighting gender power relations and the construction of the “other” identity in the text.

Epilogue

Odysseus’s journey is a timeless allegory for human existence – a narrative that transcends the narrow confines of myth and transforms into a universal symbol of the human quest for identity, purpose, and completion. The resourceful king of Ithaca symbolizes the relentless human effort to overcome obstacles, face dangers, and ultimately return home – whether literal or metaphorical.

Through Odysseus’s adventures, Homer reminds us that life is not just the destination but the journey itself, with its trials, losses, joys, and discoveries. The Odyssey continues to resonate in our collective consciousness, calling us to recognize in our own path our personal nostos – our own journey back to who we truly are.

Clay calyx-krater with red-figure decoration, attributed to the Persephone Painter, depicting Odysseus pursuing Circe, circa 440 BC.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many years did Odysseus’s journey back to Ithaca last?

Odysseus’s journey back from Troy to Ithaca lasted ten whole years. If we include his ten-year participation in the Trojan War, Odysseus was away from his homeland for a total of twenty years. This long absence is a key element of the plot, as it creates the conditions for testing Penelope’s faithfulness and the threat of the suitors to the throne of Ithaca.

What were the most significant adventures of Odysseus during his return?

During his long journey back from Troy, Odysseus faced numerous trials. Among the most iconic adventures are the blinding of the Cyclops Polyphemus, dealing with the sorceress Circe, passing between Scylla and Charybdis, resisting the song of the Sirens, and his seven-year stay on the island of the nymph Calypso. Each adventure tested different aspects of his character.

Why did Poseidon pursue Odysseus during his return?

Poseidon’s enmity towards Odysseus stems from the blinding of his son, the Cyclops Polyphemus. When Odysseus blinded Polyphemus to escape from his cave, the Cyclops prayed to his father for revenge. Poseidon, as the god of the sea, relentlessly pursued Odysseus, causing storms and shipwrecks that dramatically prolonged his journey back to Ithaca.

How did Odysseus manage to deal with Penelope’s suitors?

Upon reaching Ithaca, Odysseus disguised himself as a beggar with Athena’s help to observe the situation in his palace. He collaborated with his son Telemachus, the swineherd Eumaeus, and the cowherd Philoetius to plan the extermination of the suitors. The decisive moment came with the bow contest, where Odysseus proved his identity and then used the same bow to exterminate the suitors.

What is the timeless significance of Odysseus’s nostos in world literature?

Odysseus’s journey back has inspired countless literary works worldwide, from antiquity to the present. The concept of nostos, the return home, has become a fundamental archetype symbolizing the search for identity and self-awareness. Modern authors like James Joyce and Derek Walcott have recreated the Homeric journey in new contexts, while the concept of return remains a central theme in many forms of storytelling.

Bibliography

- Bakker, E. J., Montanari, F., & Rengakos, A. (2006). La poésie épique grecque: métamorphoses d’un genre littéraire. Vandoeuvres: Fondation Hardt pour l’études de l’Antiquité classique.

- Doukas, K. (1993). To megalo mystiko tou Homērou: Odysseia. Athēna: Ekdoseis Astēr.

- Finley, M. I. (2002). The World of Odysseus. New York: New York Review Books.

- Freely, J. (n.d.). Traveling in the Mediterranean with Homer. Athens: Patakis Publications.

- Homer, & Laffon, M. (2007). The Odyssey – The Return of Ulysses – Complete Text. Paris: Éditions De La Martinière Jeunesse.

- Malkin, I. (1998). The Returns of Odysseus: Colonization and Ethnicity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Mantis, K. (n.d.). Text Analyses: G. Ioannou “The Only Inheritance”. Athens: Gutenberg Publications.

- Trypanis, K. A. (1986). Greek Poetry: From Homer to Seferis. Athens: Estia.