Hercules, the most prominent of the heroes of Greek mythology, faced twelve exceptionally demanding labors at the behest of Eurystheus, king of Mycenae. The fifth of these labors, the cleaning of the Augean stables, is a characteristic example of the hero’s inventiveness and cleverness. Augeas, king of Elis, had vast herds of cattle, whose stables had not been cleaned for thirty years. Eurystheus, knowing the magnitude of the challenge, set the condition of completing the cleaning in just one day.

The story of Hercules and the Augean stables is an integral part of the Greek mythological tradition and has remained alive through the centuries. The hero, faced with this seemingly impossible task, demonstrated exceptional ingenuity by diverting the flow of the Alpheus and Peneus rivers. The rushing waters of the rivers swept away the animal dung, cleaning the stables in no time. However, Augeas’s refusal to pay the agreed reward led to a series of events that significantly affected the course of the myth.

The Meeting with Augeas and the Agreement

The first meeting of Hercules with Augeas, king of Elis, was characterized by the imposing presence of the vast royal estates that stretched across the fertile plain of the region. Augeas, son of the Sun according to one version of the myth, owned the largest herds in the Peloponnese, with more than three thousand cattle and countless other animals. The stables, which had not been cleaned for thirty whole years, had become a huge source of pollution for the area.

The negotiation between the hero and the king was particularly delicate, as Hercules, knowing the value of the undertaking, proposed an agreement that would secure him one-tenth of the royal herds as a reward for cleaning the stables in just one day. Augeas, considering the task impossible and convinced of the hero’s failure, accepted the proposal without a second thought, sealing the agreement with an oath in front of his son, Phyleus.

The trial of Hercules was a challenge that required not only superhuman strength but also exceptional intelligence (Herschbach). The choice of this particular labor by Eurystheus was not accidental, as it aimed to humiliate the hero through a task considered demeaning for a man of his social standing.

Before starting his work, Hercules carefully toured the area, studying the geography of the place and the flow of the Alpheus and Peneus rivers, as this knowledge would prove crucial for the success of the undertaking. The careful observation of the terrain and water resources revealed to the hero the possibilities offered by the natural environment for the execution of the labor.

The timing of the execution of the labor was also crucial, as Hercules waited for the right season when the river waters would be forceful enough to serve his plan. The preparation of the undertaking required detailed planning and precise calculation of the natural forces that needed to be harnessed.

Hercules’ Method

The methodology chosen by Hercules for the execution of his fifth labor is a characteristic example of the acumen that distinguished him. Instead of approaching the task with the conventional method of manual cleaning, he demonstrated exceptional inventiveness by harnessing natural forces to his advantage.

The execution of his plan began with a careful study of the topography and hydrological characteristics of the area. At dawn, the hero began his work by opening two large breaches in the walls of the stables, one at the entrance and one at the exit, thus creating the necessary conditions for the implementation of his plan. In the stables of Augeas, the accumulated filth of three decades posed an unprecedented challenge that required an equally unprecedented solution (Adamopoulou).

The technique applied by Hercules was based on the diversion of the Alpheus and Peneus rivers, a process that required an exceptional understanding of hydraulic principles and the natural flow of waters, as the force of the rivers had to be channeled in such a way as to ensure the effectiveness of the cleaning without causing damage to the facilities or endangering the animals.

With a series of carefully designed interventions in the natural relief of the area, including the construction of makeshift dams and channels that required the use of boulders and tree trunks, Hercules managed to create a complex water management system that would serve his purpose.

The cleaning process, completed in one day, was a remarkable engineering achievement of antiquity, as the force of the waters, precisely directed through the stables, swept away the accumulated dung of thirty years, leaving behind clean and hygienic spaces for the animals of King Augeas.

The Contentious Reward for Hercules’ Labor

A King’s Evasion and a Son’s Defense

The monumental task of cleaning the Augean Stables, a legendary supreme feat of strength and skill, ended in a dispute between the great Hercules and King Augeas. Despite Hercules’s undeniable success in performing this task, King Augeas–who, as a side note, has namesakes that persist in Greek history and even today–did not reward Hercules as he promised. He invented various lies and excuses to avoid paying up. (He was a real piece of work.) What happened next is an echo of history. Hercules did what any reasonable person would do after his agreements had been breached: He took his case to court. The judge ruled in favor of Hercules, and that’s how we got the “Sleeping Beauty” story for the next few centuries.

Hercules accomplished a great deal, yet Augeas had the nerve to argue he was unworthy of the compensation promised. Augeas attempted to weasel out of paying Hercules what he had coming by claiming that Hercules had not really done anything superhuman to merit all that gold. Instead of putting up with Augeas’s baloney, Hercules confronted him and, naturally, in such tales, Augeas usually ends up with an axe and losing his head. Phyleus, son of King Augeas, is often featured in such tales, too, as a character who stands up both for Hercules and for his father (whom Hercules doesn’t actually kill—the whole thing’s a bit of an edge case in terms of earned heroic rewards).

Consumed by fury at his son’s rebellion, Augeas took drastic action and exiled Phyleus from Elis. At the same time, he stubbornly refused to acknowledge Hercules’ truly monumental labor as one of the twelve tasks Eurystheus had assigned to him. And Hercules, of course, had done this labor in service to his father. This act of defiance, then, was not just a personal slight against our hero; it was a grave transgression against the sacred laws of hospitality and honor that were the foundation stones of ancient Greek society. And what was transgressed could not go unpunished. The chasm that this act created between father and son and between the two hereunters and the path their story takes into the delicate political balance of the Peloponnese maintained the next part of the balance in that fragile equilibrium.

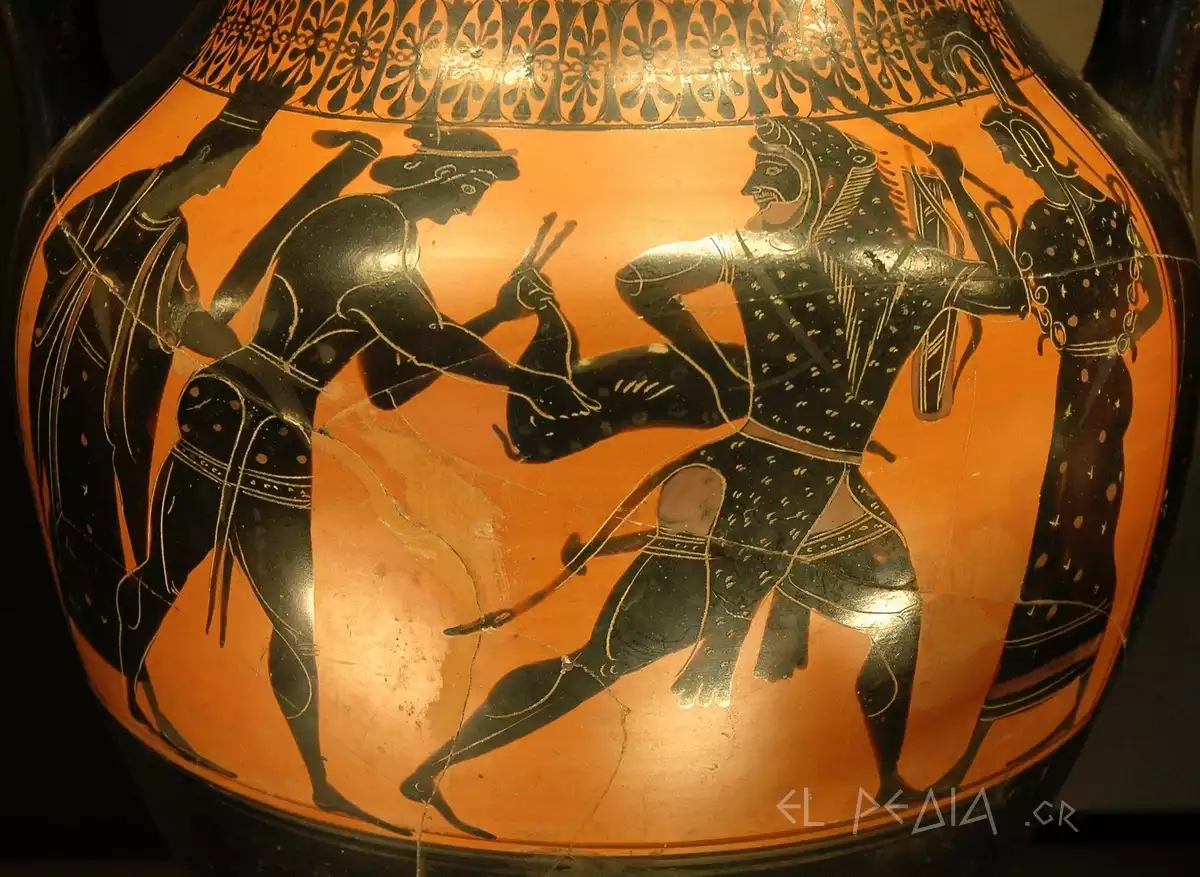

Detail from an Attic black-figure amphora of 530-520 BC depicting Hercules capturing the Ceryneian Hind, in the presence of the twin deities.

Hercules’ Legacy in Ancient Elis

The story of the cleaning of the Augean stables by Hercules is one of the most instructive myths of ancient Greek tradition. The hero’s achievement is not limited to solving a seemingly insurmountable problem but highlights the importance of ingenuity and innovative thinking in facing challenges.

The utilization of natural forces to achieve his goal is an early example of environmental engineering, while the subsequent conflict with Augeas and the restoration of justice underscore the importance of adhering to moral values and agreements in ancient Greek society.

The legacy of this myth remains relevant, as it highlights timeless values such as inventiveness, perseverance, and justice, while also warning of the consequences of hubris and arrogance.

elpedia.gr

Bibliography

Adamopoulou, G. “Once Upon a Time… Ancient Myths from the Region of Elis.” Culture-Journal of Culture in Tourism, Art & Education (2022).

Herschbach, D. “The Thirteenth Labor of Hercules.” Thirteenth Labor (2020).