Bust of Athena type “Pallas of Velletri”, a copy from the 2nd century AD from a statuette by Crisilus in Athens (430-420 BC). Glyptothek Munich, no.213.

Greek mythology is one of the most important pillars of world culture, with timeless influence on art, literature, and philosophy. At the center of this complex system of narratives and symbols are the Olympian gods, those powerful entities that inhabited Olympus and determined the course of humans and the world. Ancient Greek thought, through mythological narratives, sought to interpret natural phenomena, human relationships, and existential questions, creating a system that reflected the social structures and cultural values of the time.

In contrast to monotheistic systems, Greek religion was characterized by a pluralism of deities with anthropomorphic traits and human weaknesses. Zeus, as the leader of the Greek pantheon, gained his power through a cosmic struggle, not through primordial creation. As Kampourakis points out, in Greek mythology, Zeus was a later figure, seizing the universe “coup-style” after it had already been created by others (Kampourakis).

The complexity of these myths, with their multiple versions and variations, reflects the pluralism of ancient Greek thought and the absence of a dogmatic approach to divine matters. The Greeks allowed for the parallel existence of different narratives, often contradictory to each other, thus creating a rich mythological landscape that continues to fuel our imagination and thought to this day.

Marble head of Apollo Sauroktonos from the 2nd century AD from Kifisia, likely from the villa of Herodes Atticus. The best Roman copy of the bronze statue by Praxiteles.

The Olympian Gods and Their Hierarchy

Zeus and the Establishment of His Power

At the top of the hierarchy of the Olympian gods is Zeus, the father of gods and men, who seized power after an epic struggle against his father, Cronus. His rise to power marks a critical transition in Greek theogony – from the age of the Titans to the age of the Olympian gods. After swallowing Metis (the personification of wisdom), Zeus gained the ability to maintain order in the universe through law and justice.

Zeus’s power was not absolute, as one would expect from a supreme ruler. According to Greek myths, even he was subject to Fate, the primordial force that determined the course of all beings. This delicate balance between power and limitations reflects the deep Greek perception of cosmic order, where no being, no matter how powerful, can transcend the fundamental laws of the universe.

The Twelve Olympians and Their Domains of Influence

The Greek pantheon of major deities consisted of twelve gods and goddesses, each with a specific domain of influence. Besides Zeus, Hera protected marriage, Poseidon ruled the seas, Hades the underworld, Athena embodied wisdom and military strategy, Apollo represented art and prophecy, Artemis hunting and wildlife, Aphrodite love, Ares war, Hestia the hearth and family, Hermes trade and communication, and Hephaestus craftsmanship and metallurgy.

This division of cosmic responsibilities reflects the tendency of the ancient Greeks to categorize and organize the world around them, attributing different aspects of human experience and natural phenomena to different deities. (Search for more information with the word: Greek religion twelve gods)

Relationships and Conflicts Among the Gods

The relationships among the Olympian gods were characterized by complexity and often intense conflicts. Rivalries, love affairs, alliances, and betrayals were common elements of their interpersonal dynamics. In many cases, these interactions mirrored the complex human relationships, allowing the Greeks to recognize their own feelings and behaviors in the stories of the gods.

Particularly interesting are the marital disputes between Zeus and Hera, which often arose from the former’s infidelities. These narratives, while seemingly merely entertaining, reveal deeper elements of ancient Greek society and its perceptions of power, gender, and marital relationships.

Olympus as the Center of Divine Power

Olympus, the highest mountain in Greece, served as the symbolic and mythological center of divine power. According to Konstantinidis, the Olympian gods had as their “perpetual dwelling and place of residence” Olympus, which functioned as their heavenly kingdom, separated from the world of mortals (Konstantinidis).

This placement of divine residence reflects the ancient Greeks’ perception of the distance between the human and the divine, while simultaneously suggesting the Greek tendency to connect supernatural elements with the natural world. Olympus was not merely a place of residence but a symbol of transcendence and order, a cosmic center from which the divine power governing the world emanated.

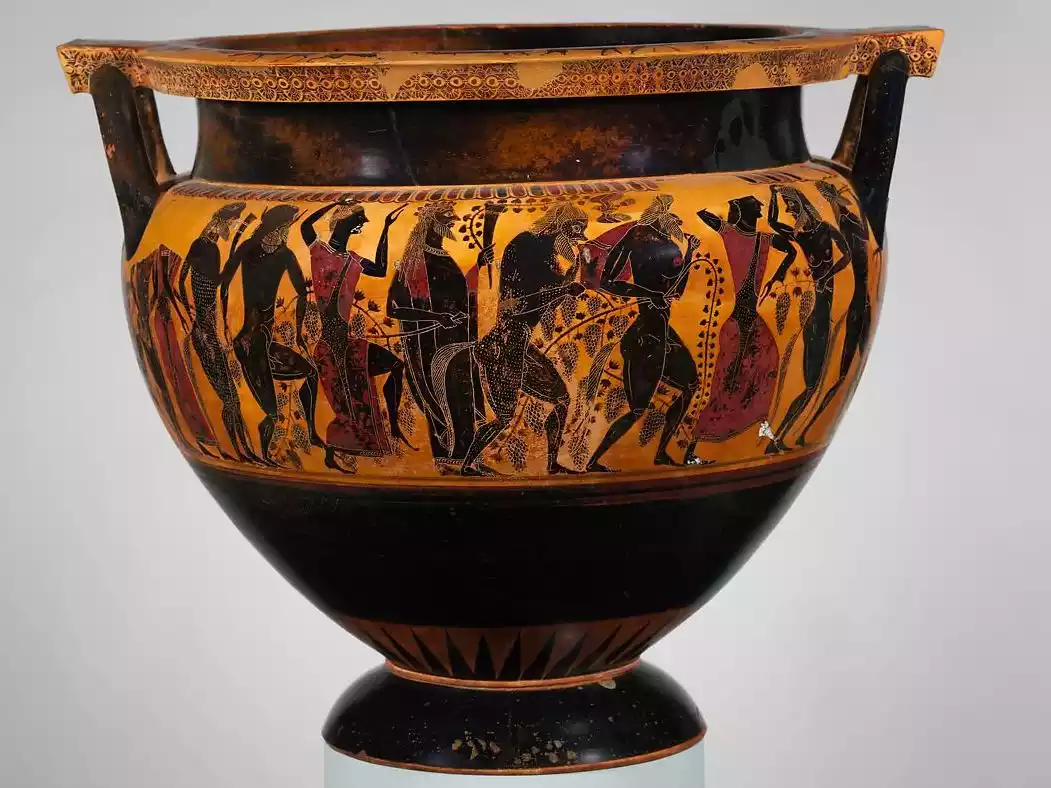

Terracotta column krater attributed to Lydos, circa 550 BC. It depicts the return of Hephaestus to Olympus, accompanied by Dionysus, satyrs, and maenads.

Cosmogony and Theogony in Greek Mythology

From Chaos to Order: The Birth of the World

Cosmogony in the Greek mythological tradition begins from the vast Chaos, a primordial state of disorder and void from which the first cosmic entities emerged. From this primordial state, Gaia (Earth), Tartarus (the deepest part of the Underworld), Eros (the force of attraction and reproduction), Erebus (the primordial darkness), and Nyx (Night) were born. These entities were not merely gods with anthropomorphic traits but cosmic forces that shaped existence and determined the fundamental laws of the universe.

Gaia, the primordial mother, gave birth to Uranus (Sky) without union. From the union of Gaia and Uranus came the Titans, the Titanides, the Cyclopes, and the Hecatoncheires, thus paving the way for the next generations of deities and the evolution of cosmic order.

The Titanomachy and the Gigantomachy

The journey from Chaos to cosmic order is characterized by violent conflicts between successive generations of gods. The first great conflict, known as the Titanomachy, occurred when Cronus, at the urging of his mother Gaia, overthrew his father Uranus. Later, Zeus and his brothers overthrew Cronus, leading to the establishment of the power of the Olympian gods.

The next great conflict, the Gigantomachy, was the war between the Olympian gods and the Giants, children of Gaia from the blood of the castrated Uranus. These cosmic battles reflect the pattern of progress through conflict and the replacement of the old by the new, a fundamental concept in Greek thought.

The Role of Primordial Forces

Beyond the anthropomorphic gods, Greek mythology recognized the existence of primordial forces that surpassed even the power of the Olympians. The Fates (Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos) played a decisive role, weaving the thread of life for every mortal and immortal. Even Zeus was subject to their decisions, suggesting that in the Greek worldview, even the highest divine power is subject to some fundamental cosmic laws.

Other primordial forces included Nemesis (divine justice), Ananke (cosmic necessity), and Chronos, often personified as Aion or Time. These entities represented abstract principles governing the functioning of the world and set the limits of divine and human action. (Search for more information with the word: cosmogony of the ancient Greeks)

The Hesiodic Theogony and the Systematization of Myths

The most comprehensive presentation of Greek theogony is found in Hesiod’s work “Theogony,” which attempts to systematize various mythological traditions. Hesiod presents a genealogy of the gods, starting from Chaos and reaching the ancient myths that describe the Olympian gods and their descendants.

His work represents an effort to introduce order and coherence into the complex and often contradictory mythological tradition of ancient Greece. It is an early attempt to understand the world through narrative, a venture that reflects the tendency of the ancient Greeks to seek order and meaning in an apparently chaotic universe.

The Orphic Tradition and Alternative Cosmogonies

Alongside the dominant theogonic tradition, there were also alternative versions of cosmogony, the most significant being the Orphic tradition. In Orphic mythology, the origin of the world is described differently, with the cosmic egg playing a central role. From this egg is born Phanes (or Ericapaeus), a primordial deity representing light and life.

These variations suggest the diversity and pluralistic nature of Greek religious thought, where different cosmogonic narratives could coexist. The complexity of Orphic and other alternative traditions adds depth to our understanding of the diversity of Greek mythology and its flexibility in addressing fundamental existential questions.

Attic black-figure amphora from the workshop of Antimenes, around 510 BC. It depicts Athena and Heracles in a chariot with gods and Dionysus with Artemis, Apollo, Leto, and Hermes.

The Influence of Ancient Myths on the Modern World

Literary and Artistic References

The influence of Greek mythology on modern literature, art, and culture is undeniable and timeless. From Shakespeare and Dante to contemporary writers, the archetypal patterns and characters of Greek myths continue to be a source of inspiration. Particularly in the literary tradition, Greek mythology remains, as Jensen points out, “an inexhaustible source of universal wisdom” that invites us to reflect on the fundamental questions of human existence (Jensen).

In the visual arts, the iconography of Greek myths has shaped European aesthetics for centuries, from the Renaissance to modern cinema and digital media. Representations of gods, heroes, and mythical scenes continue to communicate universal ideas and emotions, making ancient myths a living part of contemporary cultural expression. (Search for more information with the word: influence of Greek mythology on modern art)

Psychological Interpretations of Greek Mythology

In the field of psychology, Greek mythology has provided rich material for understanding the human soul. Carl Jung developed the theory of archetypes based partly on Greek myths, while Sigmund Freud borrowed the name of Oedipus to describe a critical stage of psychosexual development. The gods of the Greek pantheon represent, according to these approaches, different aspects of human personality and consciousness.

Modern psychological approaches to the myths treat them as collective narratives that help in understanding human behavior and our deeper motivations. Through the adventures and conflicts of the gods and heroes, we can perceive the complex dynamics that govern our soul and our interpersonal relationships.

The Global Heritage of Greek Myths

Greek mythology is an integral part of the world’s cultural heritage, transcending the geographical and temporal boundaries of ancient Greece. The Greek mythology, as described in Rose’s work, provides “anthropological constants” that remain valuable in an increasingly complex world (Rose).

These myths continue to be taught in schools and universities worldwide, adapted into modern literary and cinematic works, and are the subject of scholarly study in various fields. Their timeless appeal is due to their ability to capture fundamental human concerns and offer symbolic narratives that help us understand ourselves and the world around us.

Terracotta stamnos height 39.9 cm with a Dionysian entourage. The fine rendering of the figures reflects the artistic maturity of Athens during the Periclean period.

Different Interpretations & Critical Assessment

The polysemy of Greek mythology has provoked a multitude of different interpretative approaches from scholars in various fields. Vernant argued that myths are coded expressions of social structures, while Burkert emphasized their anthropological dimension as a reflection of ritual practices. Dowden developed an ethnological approach linking myths to local traditions, opposing the universality attributed to them by Campbell. Kirk categorized myths based on functionality, while Nagy focused on their poetic dimension. Kahil and Edmunds analyzed the timeless transformation of myths, suggesting that their continuous reinterpretation is an integral part of their dynamic nature.

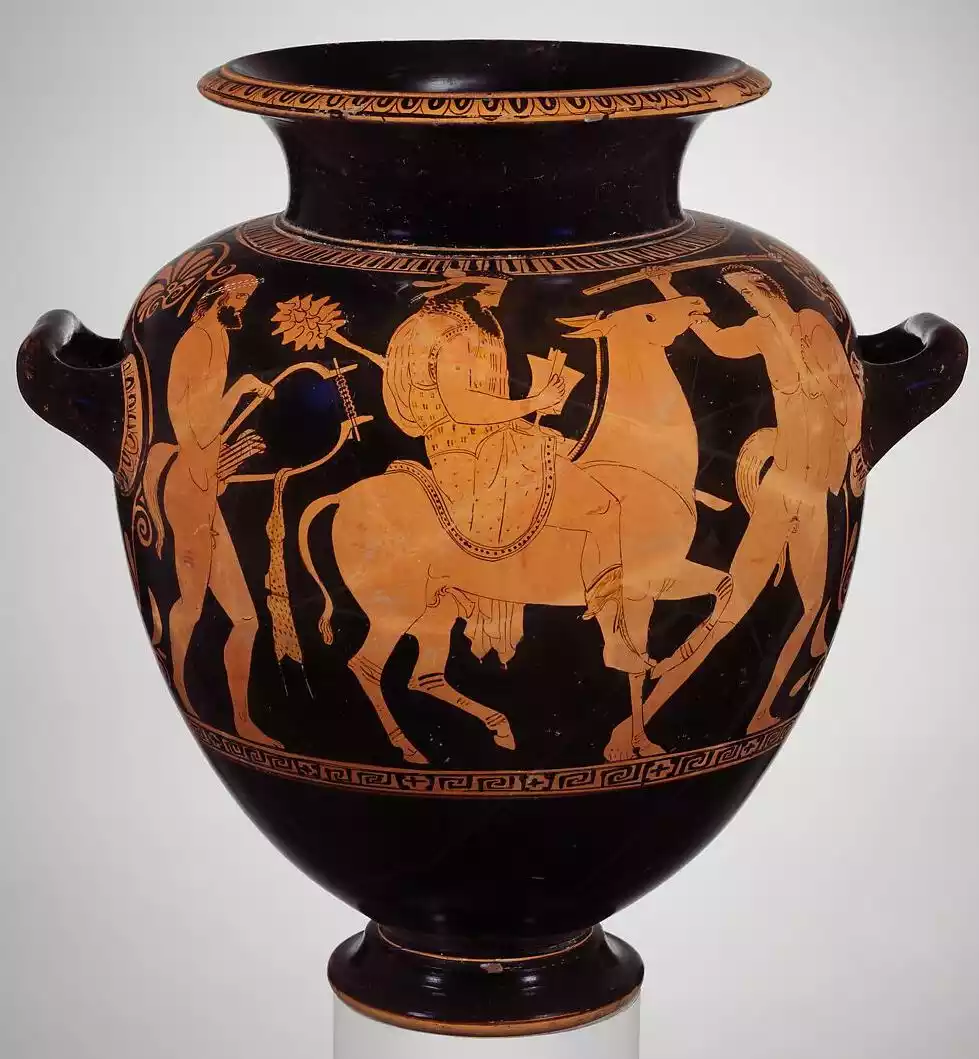

Black-figure column krater from the Archaic period (circa 540 BC) depicting the Gigantomachy with Athena and on the reverse side Dionysus with satyrs and maenads. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund, 1924.

Epilogue

Greek mythology remains an inexhaustible wealth of symbols, narratives, and archetypes that continues to nourish modern thought. In the complex system of the Olympian gods and cosmogonic narratives reflects the ancient Greeks’ effort to understand and interpret the world around them. Beyond their historical and cultural value, these myths offer timeless models for addressing the fundamental existential questions that concern every human society.

In the modern era, as humanity faces new challenges and quests, Greek mythology continues to be a source of inspiration and reflection, reminding us that fundamental human concerns remain unchanged through the ages. The dialectical relationship between chaos and order, the issue of power and morality, the coexistence of the rational and the irrational, remain relevant issues that the ancient myths approach with timeless insight.

Black-figure krater, 520-510 BC, with masks of Dionysus and satyr between the eyes. The iconography is linked to the political-religious initiatives of the Peisistratids.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who were the most important gods in the Greek pantheon?

The twelve main gods of Greek mythology were Zeus (king of the gods), Hera (protector of marriage), Poseidon (god of the sea), Demeter (goddess of agriculture), Athena (goddess of wisdom), Apollo (god of light and the arts), Artemis (goddess of hunting), Ares (god of war), Aphrodite (goddess of love), Hermes (messenger of the gods), Hestia (goddess of the hearth), and Hephaestus (god of fire and metallurgy). There were also many secondary deities that complemented the mythological system.

How does Greek mythology differ from other ancient mythologies?

Greek mythology stands out for the intense anthropomorphism of its gods, who are presented with human emotions, weaknesses, and passions. Unlike other mythological systems, the gods of the Greek pantheon are not entirely good or evil, but complex characters with contradictory elements. Additionally, Greek myths are characterized by a pluralistic approach that allowed for the parallel existence of different, even contradictory versions of the same story.

What is the significance of the Titanomachy in ancient Greek myths?

The Titanomachy, the great battle between the Olympian gods and the Titans, is a central episode of Greek mythology as it symbolizes the transition from a primordial state of chaos to a new cosmic order. This cosmogonic conflict represents the struggle between old and new forces, the replacement of older cosmic principles with newer ones, and the establishment of a new hierarchy that will govern the universe under the power of the Olympian gods.

How have Greek myths influenced modern literature and art?

The myths of Greek mythology are a timeless source of inspiration for literature, the visual arts, theater, and cinema. From Shakespeare to Joyce and from Baudelaire to Camus, leading writers have drawn on mythological patterns. In modern times, Greek myths are reinterpreted and redefined in popular culture, comics, video games, and blockbuster films, demonstrating their resilience over time.

What psychological interpretations have been given to the symbols of Greek mythology?

The psychoanalytic approach views the myths of Greek mythology as expressions of unconscious mental processes. Freud identified in the myth of Oedipus the expression of fundamental psychosexual conflicts, while Jung interpreted the gods as archetypes of the collective unconscious. Modern psychologists recognize in the myths symbolic representations of fundamental existential anxieties and developmental stages, considering them valuable tools for understanding the human soul and behavior.

Bibliography

- KONSTANTINIDES, Georgios. Homeric Theology, or, the mythology and worship of the Greeks. 1876.

- History Brought Alive. Greek Mythology: Explore The Timeless Tales Of Ancient.

- Hederich, Benjamin. Graecum lexicon manuale. 1803.

- Jensen, Lars. Greek Mythology. 2024.

- Kampourakis, Dimitris. A Drop of Mythology. 2024.

- PAPARRHEGOPOULOS, Demetrios. Orpheus. Pygmalion. Ancient myths. [Poems.]. 1869.

- Rodríguez, Isabel. The Great Book of Greek Gods: A Practical Guide for. 2024.

- Rose, Herbert J. Greek Mythology: A Handbook. 2003.