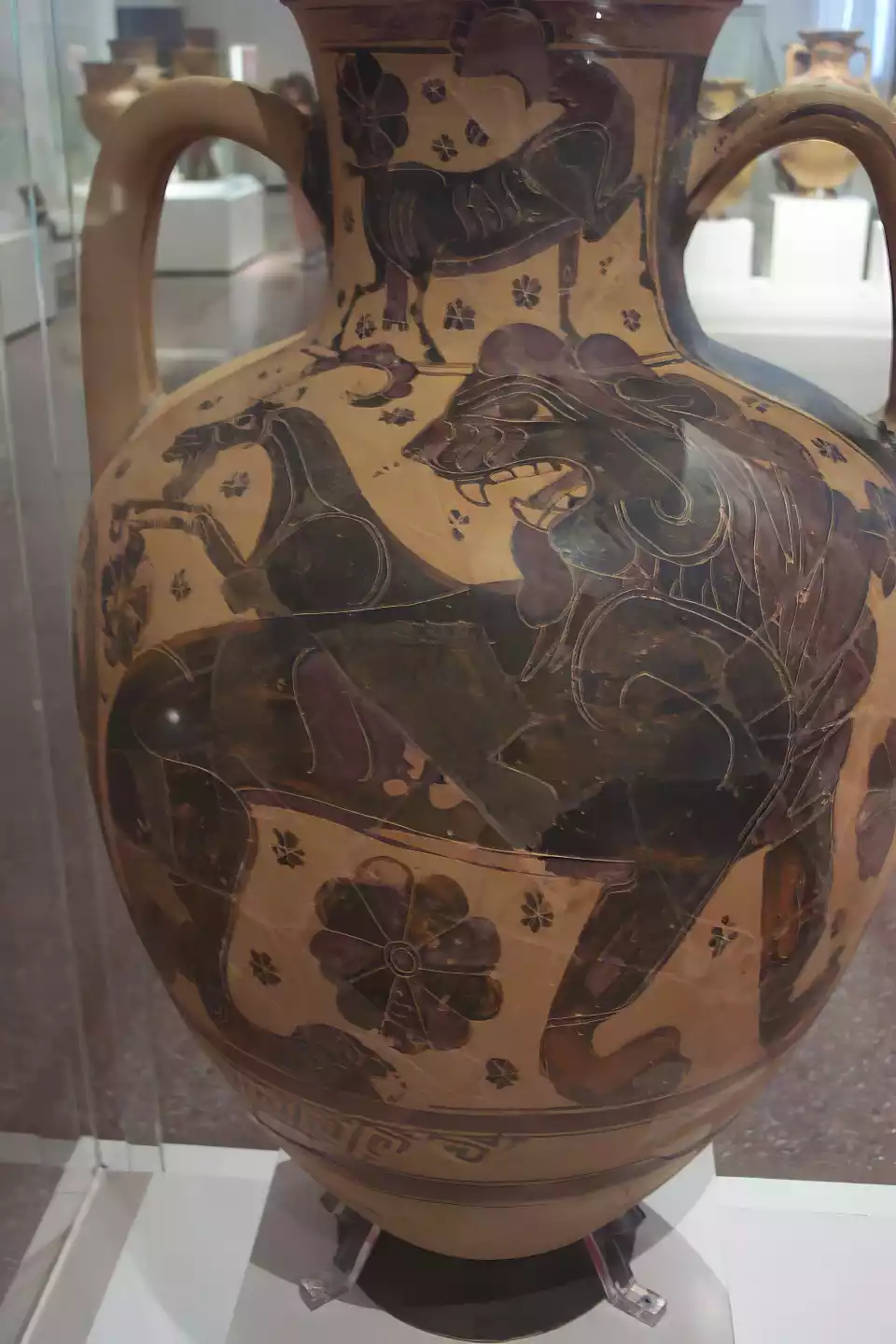

The Chimera on an Attic black-figure vase. The hybrid monster of Greek mythology is depicted with dynamism. National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

In the vast and fascinating world of Greek mythology, few creatures ignite the imagination and inspire awe as much as the Chimera. It is not merely another monster, but a symbol of unnatural union, a creature born from terror and darkness, which marked the myths with its fiery breath. Imagine a creature with the roaring head of a lion, the body of a wild goat emerging from its back, and a tail that ends in the serpentine head of a venomous reptile. This description, though repulsive, barely scratches the surface of the horror embodied by the Chimera, making it one of the most recognizable and terrifying adversaries for the heroes of antiquity.

Its origin is as monstrous as its appearance. Born from the union of two of the most fearsome figures in mythology, the giant Typhon and Echidna, the mother of all monsters, the Chimera inherited a power and ferocity that made it a scourge for the land of Lycia in Asia Minor. The ancient Greeks saw it not only as a physical threat but also as a harbinger of evils, a sign of the gods’ wrath or a disturbance of the natural order (Konstantinides). Its appearance was often associated with disasters, such as storms or natural phenomena, enhancing the aura of terror that surrounded it. Its story is inextricably linked to the hero Bellerophon, who undertook the dangerous task of slaying it, in a narrative that highlights courage in the face of the impossible. The Chimera, therefore, is not merely a creature of fantasy, but a powerful symbol in mythology (Dodd), an embodiment of chaos and challenge that heroes were called to confront.

The Anatomy of Terror: What Did the Chimera Look Like?

The description of the Chimera in ancient sources is quite consistent, outlining a creature that embodied the wildest characteristics of three different animals. This hybrid nature was key to its terrifying existence, a visual shock that provoked disgust and fear.

The Lion’s Head

At the front, the Chimera was dominated by a fierce lion’s head. This was not merely a decorative element, but the center of its aggressive power. The fangs, strong jaws, and its roar echoed the strength of the king of beasts, but distorted into something more primal and malevolent. The lion’s head symbolized raw power and irresistible momentum, making a frontal assault against it nearly impossible.

The Body of the Goat

The most strange and unnatural element was the body of a goat (or, more often, a second goat head) sprouting from its back, between the lion’s head and the snake’s tail. This goat element added a surreal and grotesque dimension to the already monstrous form. Although the goat is not traditionally considered as wild an animal as the lion or the snake, its presence in this incongruous spot emphasized the unnatural nature of the Chimera, a distortion of creation itself. Some interpretations suggest that this head may symbolize lust or cunning, adding another layer to the complexity of the monster.

The Snake’s Tail and the Fiery Breath

The back of the Chimera ended in a long, serpentine tail, often with a venomous snake head at the tip, ready to strike. The snake, a symbol of cunning, danger, and connection to the underworld, completed the triple threat. However, the most deadly weapon of the Chimera was its ability to exhale fire. This fiery breath could incinerate everything in its path, turning the land to ash and making its approach lethally dangerous. It was this trait that made it a true scourge, capable of desolating entire regions.

Dark Legacy: The Origin of the Chimera

The horror that the Chimera evoked was not random, but deeply rooted in its origin. It came from a lineage of monsters that symbolized the most primal and chaotic forces of the universe, as perceived by the ancient Greeks.

Parents of Terror: Typhon and Echidna

The father of the Chimera was Typhon (or Typhoeus), a gigantic, winged demon with a hundred snake heads, so powerful that he dared to challenge the authority of Zeus himself. Her mother was Echidna, a creature half-woman, half-snake, known as the “Mother of All Monsters.” This pair embodied the terror and chaos that predated the order of the Olympian gods. The Chimera, as their offspring, inherited this monstrous nature, a mix of brute strength and primal evil. Her genealogy placed her among the most notorious monstrous creatures.

Siblings of the Abyss: Cerberus and the Lernaean Hydra

The Chimera was not alone in this fearsome family. Her siblings were other notorious monsters of Greek mythology, such as Cerberus, the three-headed dog-guardian of the Underworld, and the Lernaean Hydra, the multi-headed serpent slain by Heracles. Some sources also mention Orthrus, the two-headed dog of Geryon, as her brother. This kinship underscores the role of the Chimera as part of a broader group of creatures that represented forces threatening order and humanity, emerging from the darkest corners of mythological cosmology.

Hellenistic mosaic with pebbles (c. 300–270 BC) depicting Bellerophon, riding Pegasus, spearing the Chimera. Archaeological Museum of Rhodes.

The Battle in Lycia: Bellerophon vs. Chimera

The myth of the Chimera is inextricably linked to the hero Bellerophon, the grandson of Sisyphus. Their confrontation constitutes a classic tale of courage, ingenuity, and divine assistance against an apparently invincible threat.

The Assignment of the Task

Bellerophon, having found refuge in the court of King Proetus of Tiryns, was falsely accused by the king’s wife, Stheneboea (or Anteia), of attempted rape. Proetus, not wanting to violate the laws of hospitality by killing Bellerophon himself, sent him to his father-in-law, King Iobates of Lycia, with a sealed letter requesting the death of the bearer. Iobates, also reluctant to kill a guest, assigned Bellerophon a series of dangerous missions, the first and most difficult being the slaying of the Chimera, which was ravaging his kingdom. He believed that the monster would accomplish what he could not.

The Role of Pegasus and Athena

Bellerophon realized that confronting the Chimera head-on was impossible due to its fiery breath. He needed a way to approach it from the air. According to most versions of the myth, the seer Polyidus advised him to tame Pegasus, the winged horse born from the blood of Medusa. With the help of the goddess Athena, who provided him with a golden bridle, Bellerophon managed to ride Pegasus. As Carpenter notes in his analysis of art and myth, Pindar describes Athena’s assistance to Bellerophon in taming Pegasus (Carpenter). This divine intervention was crucial for the hero’s success.

The Clever Strategy and the Fall of the Monster

Riding Pegasus, Bellerophon could avoid the flames of the Chimera by attacking from above (Carpenter). Realizing that his arrows were insufficient, he devised a clever plan. He took a piece of lead, secured it to the tip of his spear, and during an aerial assault, he threw it directly into the flaming neck of the monster. The intense heat from the Chimera’s fiery breath melted the lead, which flowed into its insides, causing it a horrific death. Thus, the hero defeated the monster not only with strength and divine help but primarily with cleverness, turning the Chimera’s own weapon against it.

Beyond the Myth: Symbolisms and Interpretations

The Chimera, beyond its literal existence as a mythological monster, has been interpreted in many ways over the centuries. The very word “chimera” has entered modern language to denote a deceptive hope, a utopia, or a creature made up of disparate parts (as in genetics).

In antiquity, the Chimera likely symbolized natural disasters or wild, uninhabited areas. Its origin from Lycia, a region with active volcanoes and bursts of natural gas that ignited (the so-called “eternal fires” of Olympus in Lycia), may have inspired the myth of its fiery breath. Some scholars, such as Paul Decharme, have suggested that the Chimera may have originally been a deity personifying the storm or the destructive winter, before transforming into monsters in classical Greek mythology (Decharme, Konstantinides).

Psychologically, the Chimera can be interpreted as the embodiment of our inner demons, the conflicting desires and fears we must confront. Its triple nature (lion, goat, snake) could symbolize different aspects of the human soul – aggression, stubborn denial, cunning – that must be harmonized or fought against. Bellerophon’s victory symbolizes, in this light, the triumph of reason, courage, and innovation over chaos and irrational fear.

The Chimera adorns this Apulian red-figure plate (c. 350-340 BC), attributed to the Lampas Group. Louvre Museum, Paris.

Different Interpretations & Critical Assessment

The interpretation of the Chimera and its myth is not univocal. While many agree on its descent from Typhon and Echidna and its connection to Bellerophon, the deeper symbolisms are a matter of discussion. Researchers like Decharme tend to see behind the monster an older deity of natural phenomena, perhaps linked to the geological peculiarities of Lycia. Others, like Konstantinides, focus on the Homeric definition of “monsters” as divine signs, suggesting that the Chimera may have represented the wrath of the gods or a disturbance of cosmic order. Its depiction in art, as analyzed by Carpenter, also shows an evolution in the perception of the monster over the centuries.

The Enduring Legacy of the Chimera

Echoes of Myth in Contemporary Thought

To fully appreciate the enduring legacy of the Chimera, one must delve deeper into its symbolic representation, a representation that transcends the boundaries of ancient Greece and resonates even within the cultural narrative of the United States. This creature, a bizarre amalgamation of disparate animal forms, continues to fascinate and horrify, serving as a potent metaphor for the internal and external conflicts that define the human experience. The Chimera, with its fiery breath and chaotic nature, stands as a stark reminder of the inherent struggle between the forces of order and disorder, a struggle that plays out in both individual lives and the broader tapestry of societal evolution. Just as the heroes of old, like Bellerophon, confronted this monstrous entity, so too must we confront the “chimeras” that exist within our own lives, be they personal demons or societal challenges. The very notion of a “chimera,” a term now interwoven into the fabric of our language, serves as a testament to the enduring power of this ancient myth, a myth that compels us to recognize and confront the seemingly insurmountable obstacles that lie before us. Consider, for example, how the concept of the “American melting pot,” a central element of the United States’ national identity, can itself be viewed as a kind of cultural chimera, a blending of diverse heritages into a new, complex whole, much like the mythical beast itself. The story of the Chimera, therefore, is not merely a relic of a bygone era, but a timeless narrative that continues to provoke thought and inspire reflection, urging us to embrace courage and ingenuity in the face of adversity.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly was the Chimera in Greek Mythology?

The Chimera was a terrifying, mythological monster of Greek mythology, known for its hybrid form. It is usually described as having the head of a lion, the body (or a second head) of a goat sprouting from its back, and a snake tail. One of its most dangerous characteristics was its ability to exhale fire, making it a scourge for the land of Lycia.

Who were the parents of the Chimera?

According to Greek mythology, the Chimera was the offspring of two powerful and monstrous deities, Typhon and Echidna. Typhon was a giant who challenged Zeus, while Echidna was known as the “Mother of All Monsters.” This lineage explains the monstrous nature and power of this creature.

How did Bellerophon defeat the Chimera?

The hero Bellerophon managed to defeat the Chimera through a combination of courage, divine assistance, and ingenuity. Riding the winged horse Pegasus (with the help of Athena), he approached the monster from the air and, using a spear with a lead tip, managed to melt the metal inside the Chimera’s neck by exploiting its own fiery breath.

What does the Chimera symbolize?

The Chimera, this composite creature of Greek mythology, often symbolizes the unnatural, chaos, internal conflicts, or deceptive hopes (hence the modern use of the word). It may also represent natural disasters, such as volcanic eruptions or fires, particularly in relation to the region of Lycia where the myth places it.

Were there other monsters like the Chimera in Greek Mythology?

Yes, Greek mythology is rich in hybrid and monstrous creatures. The Chimera belonged to a “family” of monsters, with siblings such as Cerberus (the guardian of the Underworld) and the Lernaean Hydra. Other well-known monsters include the Cyclopes, the Harpies, the Sirens, and the Sphinx, each with their own unique characteristics and myths.

Bibliography

- Carpenter, T. H. Art and Myth in Ancient Greece. Thames & Hudson, 2022.

- Decharme, Paul. Mythology of Ancient Greece. Pelikanos, 2015.

- Dodd, Jason. Greek Mythology: A Collection of the Best Greek Myths. J. Dodd, (No date available in snippet).

- Domē Hellada: from generation to generation: history, culture. Domē Hellada, 2003. (Snippet View).

- KONSTANTINIDES, Georgios (Macedonian). Homeric Theology, or, the mythology and worship of the Greeks. Bart kai Chirst, 1876.