Centaur mythology, deeply rooted in ancient Greece, presents us with some of the most compelling and mysterious figures of classical antiquity.

These composite beings of human and equine form have long captured the human imagination—much like our common ancestor, the Australopithecus, imagination embodied in a hybrid. They are things of an unknown past, mirroring our own. We know their secret origins, of course; we tell this narrative again and again. We tell it in dreams, with playful actors on stages, in vibrant colors, like those found in missals. Yet, not all tellings are equal. Some tellings are more revealing than others, more riotously inventive, while others stand quiet on the page, less boisterous but no less packed with meaning. All revolve around a somewhat dubious union between Ixion, king of the Lapiths, and the nymph Nephele, a cloud fashioned by Zeus. Nephele’s less-than-impressive footnote in Greek myth—cloud nymph—transcends her dubious origins and giggly status by featuring in a narrative central to the myth of the centaur. That myth soars. Look at Nephele. She’s right there with us.

The origin and nature of centaurs

The captivating nature of the creatures within the ancient Greek pantheon, particularly the centaurs, continues to resonate with us across generations. These beings, a fascinating fusion of human and animal elements, have long held a special place in the human imagination, sparking curiosity and wonder. Their hybrid form, a potent symbol of the liminal, challenges us to consider the boundaries between the civilized and the wild, the rational and the instinctual.

The lineage of the centaurs, like their very nature, is shrouded in complexity and contradiction. While the most widely circulated myth attributes their parentage to Ixion, the king of the Lapiths, and a cloud-like manifestation of Hera (Nephele), this union, orchestrated by Zeus, carries an air of deception and coercion. It speaks more to a primal, unrestrained desire than to a divine, harmonious love, highlighting the inherent duality within the centaurs’ origins and existence. This narrative, often presented as the definitive account, emphasizes the tension between their human intellect and their animalistic drives. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that this is not the sole narrative surrounding their birth. Other, less prevalent myths offer alternative parentage, suggesting connections to Apollo and Stilbys, or even Saturn, further emphasizing the multifaceted nature of these beings. This very ambiguity surrounding their origins underscores the inherent mystery and complexity that defines the centaur as a mythological figure.

The centaur’s physical form, a striking amalgamation of human and equine anatomy, embodies this duality. The upper body, human in form, represents the realm of reason and intellect, while the lower body, that of a horse, symbolizes the power of instinct and the untamed forces of nature. This inherent tension between the two halves of their being has been a subject of much contemplation. As a physicist once mused, their combined strength and speed could be described as “one ridered and the other horseed,” a vivid image of their combined power in battle. This traditional interpretation often reduces the centaur to a symbol of virility and raw physical prowess. However, such a simplistic view overlooks the deeper complexities of their symbolic representation. If we consider the figure of Chiron, the wise and noble centaur, we are compelled to question this reductive interpretation. Why would Chiron, the esteemed mentor of heroes, be associated with a figure traditionally linked to base desires and even, in some interpretations, human sacrifice? This apparent contradiction forces us to confront the multifaceted nature of the centaur, acknowledging the potential for wisdom, compassion, and even divinity within this hybrid form. The challenge lies in reconciling the seemingly contradictory aspects of their nature, acknowledging both the potential for savagery and the capacity for profound wisdom, as exemplified by the figure of Chiron.

The symbolic meaning of centaurs in ancient thought

The ancient Greek thought system doesn’t treat centaurs as ordinary creatures. They have two natures, which makes them especially suited for probing what it means to be human and the kinds of conflicts that wrinkle the human condition.

Socially speaking, centaurs are a symbol of the contrast between civilized and uncivilized beings. They can act as a reminder to humans of the fine line that can be walked or jumped over in our range of behaviors, from extreme violence (think “Centaur as Enraged Minotaur”) to wisdom (think “Centaur as Wise Sage”). Or put another way, why do we keep trying to pen in (as in “mythical beasts waiting to be tamed”) the range of human possibilities and the reasons for our passions?

Centaurs are untamed. To be even more specific, they are nothing less than the uncontrollable fury of the natural world. Obviously, they are much more than that. But this aspect of their character is especially highlighted by Alexander Scobie’s analysis in his article “The Origins of the ‘Centaurs'” (Scobie). Scobie takes a close look at the image of the centaur and asks whether it might be a representation of humankind’s basic bond with the natural world—a bond, he hints, that is fraying in our modern, civilized society.

Centaurs do not exist only in ancient Greek thought as mythical creatures. They are also found in the world of Greek philosophy, where they serve as metaphors for human nature and the moral problems that humanity must solve. For instance, in his work Politia, the philosopher Plato uses the centaur as a figure to explain his very convoluted idea of the different parts of the soul and their relationship to one another.

Even art can’t escape the symbolic significance of centaurs. Their likenesses on vases, murals, and sculptures are not for mere decoration; It’s often the case that centaurs serve as potent symbols for statements, profound and otherwise, about the nature of humanity and our condition.

In brief, the intricate origins, singular anatomy, and copious symbolism of centaurs make them the most interesting and important elements of Greek mythology. Out of all the mythological figures, the centaur is the one most often encountered in modern life, and it figure frequently appears, for instance, in comic strips. To many, the centaur is a shorthand way of signaling Greek mythology itself.

Centaurs in Greek Mythology and Literature

The captivating intensity and multifaceted quality of centaurs in Greek mythology and literature are captivating. These hybrid beings of mythology have given rise to an immense variety of tales, legends, and artistic expressions over the millennia. Although many centaurs appear in the myths of ancient Greece, none are more famous than those in the story of Hercules and the centaurs. This well-known tale describes the time when Hercules, not long returned from his famous task of ridding the world of the nymph Antaeo, visited a centaur named Pholus, who evidently served as an avatar for the wild and unruly nature of the centaur race, and who offered Hercules a drink of wine so bad that only a centaur could think it appropriate to serve a guest.

Another major myth is that of Nessus and Deianira. Nessus, a centaur, tried to abduct Deianira, Heracles’ wife, while he was helping her cross a river. After the centaur’s deception was discovered, Heracles killed him with a poisoned arrow. In his dying moments, the centaur told Deianira that his blood was a love potion and not what it actually was: a powerful toxin.

Centaurs are wild and unruly creatures, but Chiron is different from the rest of them. He is the wise and virtuous centaur. Chiron is known as the “righteous centaur.” He not only has a remarkable family tree (his divine parentage set him apart from the tragic origins of most centaur families), but also a remarkable personality. Chiron’s father was Cronus; his mother was Philyra, a sea nymph. In both his divine and his mythical origins, Chiron is exceptional, and that exceptionalism carries over into his personality. In numerous fields, Chiron was well acquainted. He was knowledgeable, for instance, in medicine, and many wondered if he was not also a god. In music, astronomy, and divination, he was equally adept, and his knowledge in these areas made him a popular tutor. He taught from his cave on Mount Pelion, and many Greek heroes were educated under his instruction.

The inheritance that Chiron bequeathed to Greek mythology is priceless. He not only instructed arts that are useful, but also delivered an almost prophetic message about humanity’s nature and about the nature of good and evil. He is a potent presence not only because he personifies the human and the divine, but also because he figures as the point of balance between civilization and nature. He is a wise figure, indeed the embodiment of wisdom.

The Battle of the Centaurs and the Lapiths

The episode most commonly associated with centaur mythology is the centaur battle with the Lapiths, often referred to as the “Battle of the Centaurs.” This conflict, which arose during the marriage of Lapith king Pirithous to Hippodamia, serves as an allegory for the clash of civilization with barbarism.

As the story goes, the centaurs were invited to the wedding but got drunk and tried to carry off the bride and other Lapith women. This attempted abduction initiated a savage, violent conflict in which the Lapiths, under the leadership of Theseus, managed – after considerable effort and a good deal of fighting – to defeat the centaurs and expel them from Thessaly. Though many works of ancient and modern art represent the battle of the Lapiths and centaurs, it is probably appropriate to question whether centaurs are the proper subjects of ancient art for this event. On what occasions were ancient boxers shown in art? What were ancient sculptors trying to convey through their depictions of human figures engaged in combat? And finally, how does the battle of the centaurs in art play into the symbolic value of the event? Centaurs inhabit not just Greek mythology and literature but also the realm of potent symbols. These half-man, half-horse beings embody the conflict between nature and culture, the animal and the human, what we might call today “the nature of man.” Historically, the Greeks have been the most significant and influential tellers of centaur stories, using them not just to explore narrative concepts but also to delve deep into philosophical and moral territory, making the centaur a powerful embodiment of conflicts that resonate in their society and ours.

Centaurs are alive and well in the collective imagination. Their complexity and ambiguity keep them in our thoughts. They are constant reminders of the eternal struggle between the different sides of man’s nature. That is probably why they’re such good symbols. They aren’t really creatures. They inhabit the human mind.

The influence of centaurs in art and culture

Centaurs have had a powerful and profound effect on art and culture from the ancient world to the present day. For artists, they are an obvious choice for showing off skills in figure drawing or painting. In terms of basic structure, they present an awesome challenge, and they appear often enough in art history that one can infer a kind of shorthand among artists for using them as an occasion to demonstrate not just their command of drawing the human figure but also the basic structures of anatomy and proportion that underpin the figure.

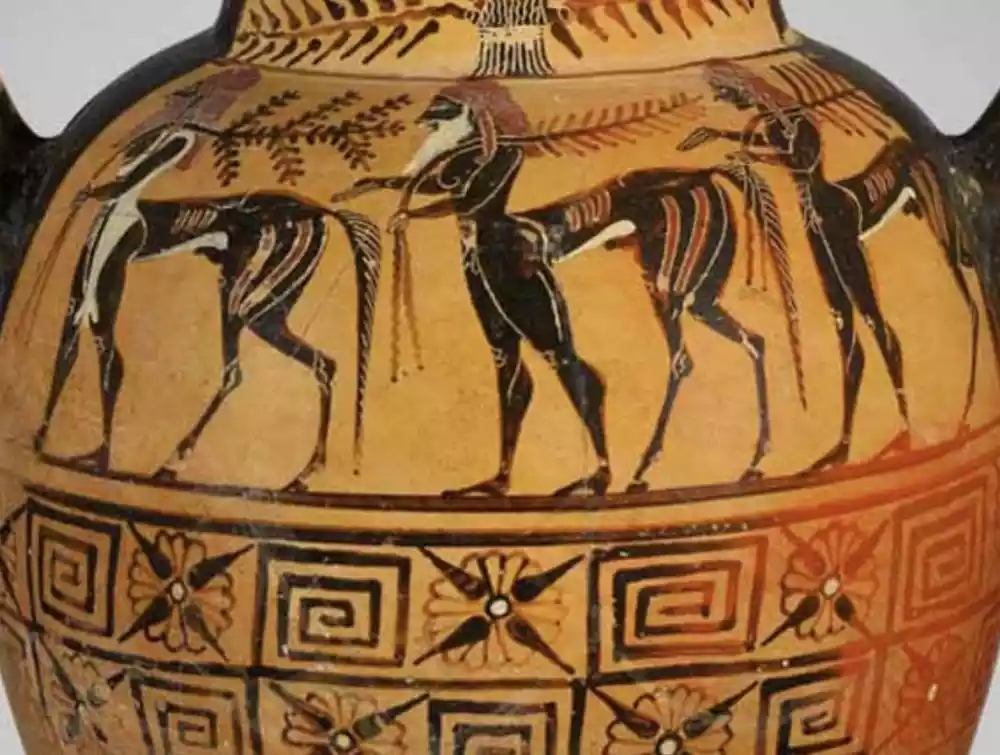

In ancient Greek art, centaurs are found in large numbers. They are not just in the run of the mill vase paintings that everybody had, but also in visible public sculptures and architectural elements. Of all the many different ways that the centaur was represented, the most popular and the most used could be called the “battle of the centaurs.” This was the epic no-holds-barred fight between centaurs and Lapiths.

An excellent representation of the Centauromachy can be found in the metopes of the Parthenon. This battle between the Lapiths and centaurs is shown on the south side of the temple. The other sides of the monument depict different mythological episodes. The north side shows a scene from the Trojan War, while the east side presents the Gigantomachy, and the west side illustrates the Amazonomachy. The confrontation in the metopes between the Lapiths and centaurs represents, in a sense, the triumph of civilization over wild nature, although it is not exactly a battle against monsters. The centaurs, after all, are not what we would ordinarily consider monsters. They represent something much nearer to our own nature—a hybrid form made up of human and animal parts.

Ceramics depict various scenes with centaurs. Frequently, they are seen either hunting or fighting, or else performing some basic mythological scene. At least, that’s the way they seem to be represented in the earliest forms of ceramics—a few generations before the use of the potter’s wheel. From that point on, ceramics seem to be used more and more often as a way to pull off the basic “art” of storytelling, with scenes more and more effectively communicated from the period before Tumulus A.

Gregory Nagy’s study of centaurs illuminates the ancient Greek conception of nature and culture. “Centaurs,” Nagy writes, “in art, function as symbols of the delicate balance between the human and animal element.” These “half-horse, half-man creatures,” he continues, “have been seen, especially in modern times, as emblems not of balance but of the absence of balance.”

Centaurs have been inspired by and obsessed over not just in antiquity but also in contemporary literature and popular culture. These legendary figures certainly are not going away anytime soon.

In literature of the fantasy type, centaurs usually seem to be enigmatic and wise. An example can be found in the Harry Potter series of tomes, where centaurs are portrayed as doing their best to remain a proud and solitude-loving almost-noble group, with the stipulation that they are very likely to be a society that enacts a “don’t tread on me” policy and might just threaten to cloud politics in the near-future world of the stories.

Centaurs have been depicted in multiple forms in cinema and television. Whether in animation or live action, on either side of the line between family-friendly and adult-oriented entertainment, the centaur has been a go-to image for storytelling about power and mystery. Like so much else in fantasy, the figure of the centaur has had its essence transformed—not in the way that cartoons might imply (for example, with the centaur in Disney’s Hercules, which has a nifty but completely false horse anatomy)—but in a way that the centaur retains, and even amplifies, its power and enigma as an image. Video games and RPGs frequently feature centaurs as characters. Centaurs often serve as wise counselors and, not infrequently, as warriors. Why not? Their horse-human duality offers some unique opportunities for character development and storylines.

The Timeless Allure of Centaurs

A nearly limitless diversity of shapes and forms exists within the legend of the centaur. No two tales of centaurs. And in our own myth-making, we look to these hybrid creatures to resolve our most essential cultural and natural mandate: the eternal conflict and reason, between nature and culture.

Centaurs today are receiving fresh interpretations and new symbolisms. They are being used, more than ever, as metaphors for the human condition in a world that is changing before our very eyes. Their mixed nature is an ideal reflection of what we now call our “Iron Age,” where the delineations between the natural and the artificial, the human and the mechanical, have become almost impossible to discern.

Resources that make possible a deep analysis of psychology and philosophy are plentiful among centaurs. They represent the complex dual nature of human beings, the simultaneous existence of opposites, and the never-ending quest for balance between the many forms our identity takes.

Science and technology benefit from the influence of centaurs. The term “centaur” is a metaphor in several scientific disciplines, including computer science and artificial intelligence. It describes hybrid states or systems that mix different, and sometimes even contradictory or complementary, characteristics.

The biology-technology future we are moving toward, which is joined at the hip with biology and technology, holds the centaur as a symbol of an impending possible synthesis and transformation of our current situation. The centaur, with the hope that what are now opposites can join together, can also be a very useful emblem of human nature in this transformative time.

To summarize, the centaur—a forever fascinating creature of ancient Greek mythology—remains captivating, for what it is and what it represents. Despite (or perhaps because of) their appearance, with their horse bodies, human torsos, and human heads, centaurs have been and continue to be fresh symbols of complexity and contradiction. With their (and our) traditionally transcendent appearance, symbols that were in ancient times used to express truths about the human condition are just as likely now to serve in the expression of our “inextricable complexity and contradiction.”

The figures of Greek mythology—those fantastically elusive creatures— are as old as humanity itself. They symbolize nature, or perhaps more accurately, the “natural” conflict within all humans, and especially all human males, since we know from the stories that centaurs are predominantly rough and rowdy. They are, in a word, nature’s attempt when “nature” resorts to “noble savagery” or headlong passions; they are figures caught in the struggle between what is lauded as “reasonable” and what is given as “wild.” They are figures of equivocation and ambivalence, or, if you wish, of contradiction, since they are seen simultaneously as children of the woods and children of the city, as creatures who are, in some respects, bound to be equestrians (horseback riders).

elpedia.gr

Bibliography

- Bremmer, Jan N. “Greek Demons of the Wilderness: The Case of the Centaurs.” Wilderness in Mythology and Religion: Approaching Religious Spatialities, Cosmologies, and Ideas of Wild Nature, 2012, degruyter.com

- Nagy, Gregory. “Can we think of centaurs as a species?” Classical Inquiries, 2019, harvard.edu

- Scobie, Alexander. “The Origins of the ‘Centaurs'”. Folklore, Vol. 89, No. 2, 1978, pp. 142-147, tandfonline.com.