Artist: Unknown Artist

Date: 9th-10th century

Dimensions: 41,8 x 27,1 cm.

Materials: Egg tempera on wood

Location: Sinai Monastery

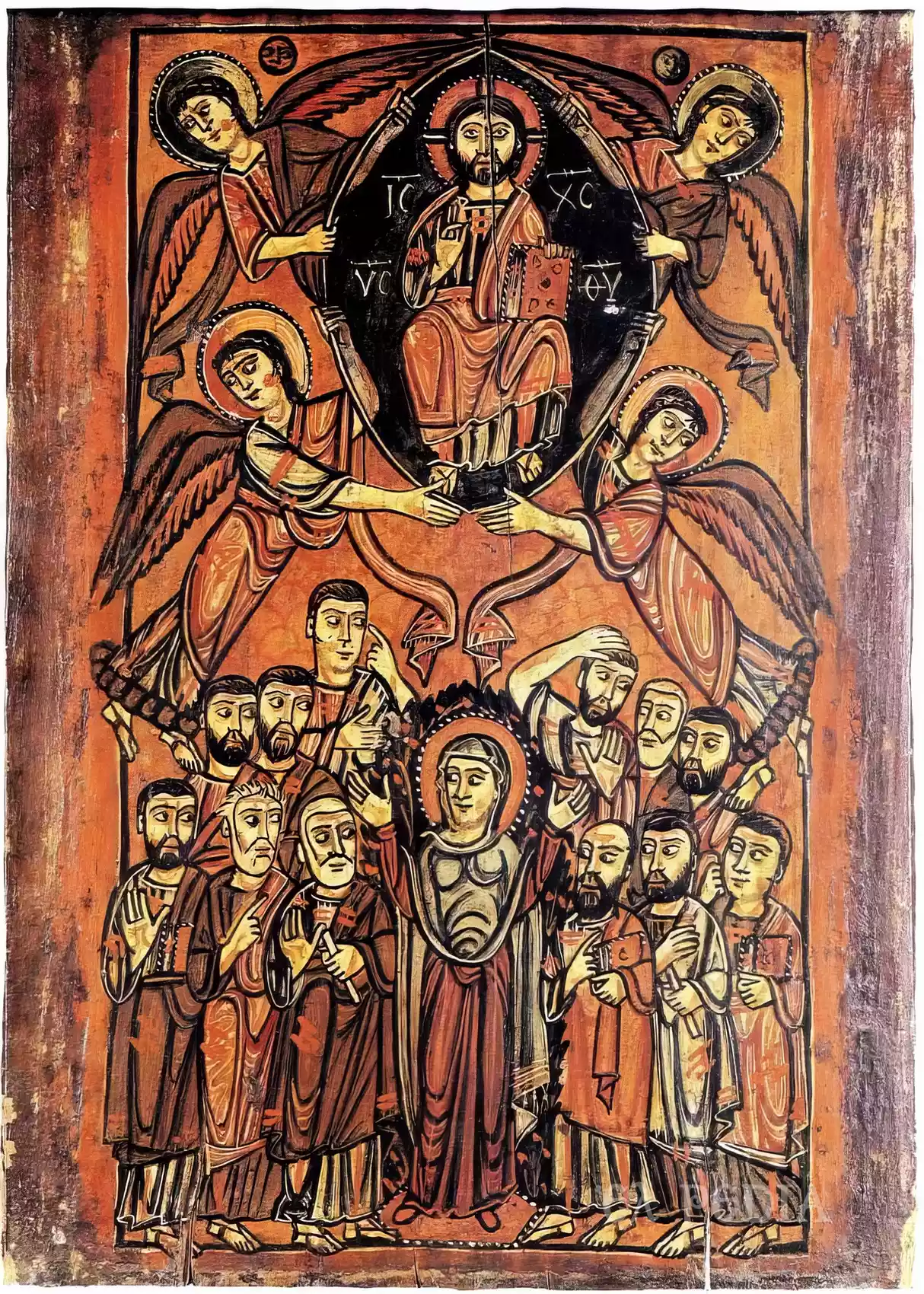

The Ascension Icon of Sinai, a masterpiece housed in the Monastery of St. Catherine, stands as a testament to the artistic dynamism of the medieval era, seamlessly blending Byzantine and Palestinian artistic traditions.

The 9th-10th century icon shows the Ascension of the Lord in a way that is both unique and deeply symbolic, inviting the onlooker to consider the divine act and its momentous consequences.

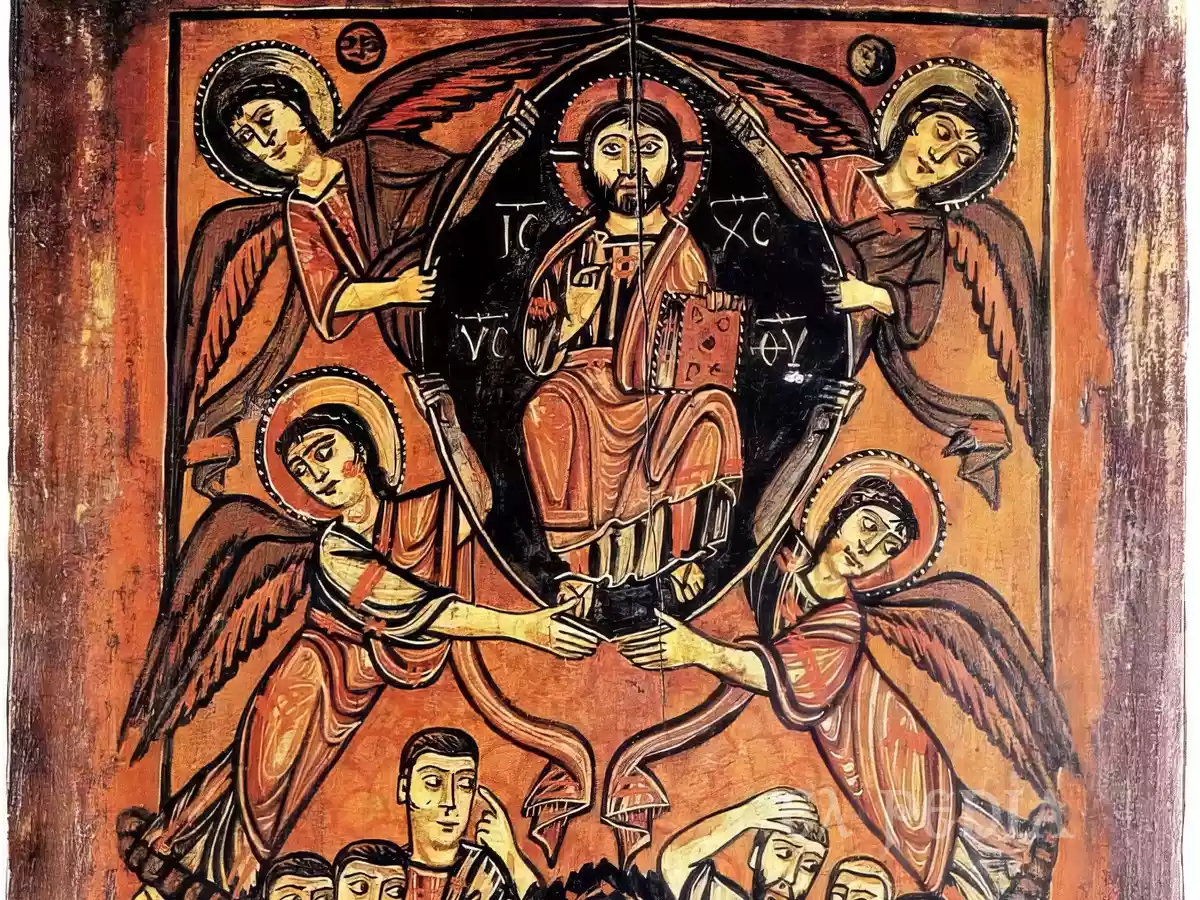

The composition of the icon unfolds across two distinct spheres, the earthly and the heavenly, that correspond to the icon’s two registers. In the upper register, Christ ascends in an ellipse of glory held aloft by four angels. Their forms and the way they hold Christ echo the celestial hierarchy—our artist’s vision of it anyway. We know this is Pseudo-Dionysius’s vision. His theology of angelic orders so inured medieval thought that few figured the heavens otherwise. Below, the Virgin and twelve apostles witness the scene. Not only must the figures in the icon hold their places while vacillating between the earthly and the heavenly, but the viewer must also negotiate these different realms as part of the icon’s visual narrative.

When considering the profound symbolism of the work, the positioning of the Virgin Mary before a sapling flowered with red blossoms is especially pregnant with meaning. The flowers echo the red in the icon’s background, which is too much the Virgin’s color, and too much the Son’s color, for any viewer to ignore. The inscription on Christ—that he is “Son of God”—is an early and undeniably potent comment on the theological significance of this event, don’t you think? Is it not also a foreshadowing of the cross and its inscription that we do not miss in the Gospels?

The artistic value of the icon is not merely symbolic. It has as much, if not more, to do with the technical execution of the piece. The artist’s masterstroke pulls color and space together into an actualized form. And that form is interpreted by the eye as possessing a kind of depth and dynamism. Drawing the viewer across the composition in a line of sight that is both natural and as-yet-unexplored, the piece gives the appearance of the forms not being static, but possessing a kind of energy that makes us think they could be moving. Add to this that, as masterpieces go, it is a pretty damn intricate piece. Those details, not really expository of anything in the way of the usual forms of divine revelation, add up to an enormous invitation for closer inspection and contemplation.

A medieval art treasure, the Sinai Ascension Icon provides a direct look into the time’s artistic and spiritual worlds. As such, it offers a unique glimpse into the time’s art, religion, even its politics. The biblical story it portrays is heart-rending: Moses is shown receiving the law from God. Moses’s ascent is depicted in a way that suggests a kind of divine interplay—a moving between God and not just a solitary figure, but a multitude of faithful witnesses.

The Ascension Icon of Sinai: Morphological Analysis

The morphological structure of the icon reveals a deep understanding of the symbolic and artistic values of medieval art. In the upper zone, the figure of Christ is depicted with a different approach from the usual one, as he is not seated or standing on a rainbow as found in most depictions of the period. The inscription “Son of God” that accompanies him is a typical example of early iconographic tradition(Nikolopoulou).

In the centre of the composition, the four angels supporting the ellipsoidal glory present an extremely interesting rendering, with the robes of the two lower ones being distinguished by their puffy fur-like rim, while the edges of their garments form an elaborate sylph-like pattern that masterfully directs the viewer’s gaze towards the figure of the Virgin. Below. Silence.

The lower zone of the icon is organized in a way that suggests a profound knowledge of the Byzantine iconographic tradition, as the Virgin is placed in the center, projected in front of a red-flowered sapling symbolizing the Flaming Vato, flanked by the apostles holding books and scrolls in an arrangement that highlights their hierarchical importance, with Peter and Andrew on her right and Paul on her left, while the presence of the precious pearls that adorn the edge of the halos and codices adds an extra dimension of spirituality to the composition(Anderson).

The execution technique is characterized by a simplistic and linear rendering of the figures, with strong contours that emphasize the structure of the composition. The colour red dominates both the plain and the garments, creating a unified chromatic harmony that enhances the spiritual dimension of the work. The use of gold in the halos and garment details adds a sense of transcendence, while the careful gradation of tones in the folds of the garments reveals the artist’s skill in rendering volume and depth.

Theological Implications and Liturgical Use

The theological significance of the icon of the Ascension at the Monastery of Sinai extends beyond the mere depiction of the historical event. The doctrinal content of the depiction is reflected in the structure of the space and the relationship between the figures. The vertical arrangement of the composition underlines the dialectical relationship between the heavenly and earthly worlds, with Christ acting as a link between the two spheres.

The presence of the Virgin Mary in the centre of the lower zone, in front of the red flowered sapling symbolizing the Flaming Vato, creates a strong symbolic association with the early Athenian theophany on Mount Sinai, recalling the special relationship between the sacred space and the divine surfaces, as the placement of the work in the Monastery of St. Catherine acquires a deeper theological dimension that links the past with the present of the monastic community(Spain).

The twelve apostles, arranged around the Virgin Mary with Peter and Andrew on her right and Paul on her left, hold books and scrolls symbolizing the spread of the Gospel message, while their posture and the direction of their gazes upwards indicate the spiritual ascension and the expectation of the Second Coming, creating a dynamic relationship between the viewer and the event depicted, which reinforces the functional use of the icon in the context of monastic worship.

In the upper zone, the depiction of Christ in the ellipsoidal glory supported by four angels presents a remarkable peculiarity, as Christ is not seated or stepping on a rainbow, as is common in other depictions of the period, but is marked with the inscription “Son of God”, an early epigraphic evidence that emphasizes his divine nature and adds an additional dimension to the theological interpretation of the work. The use of gold in the halos and details of the garments, as well as the precious pearls that adorn the edge of the halos and codices, are not merely decorative elements but symbolize the transcendent dimension of the divine and the spiritual splendor of the figures depicted.

The Palestinian artistic tradition

The Ascension icon from Sinai provides a fascinating glimpse into the ways Palestinian artists influenced Byzantine art. This icon—along with many others produced in local workshops during the Byzantine era—serves as a testament to the skill of these artists, showcasing a blend of Palestinian styles and the common visual language shared by Byzantines across the empire.

The way the figures in the icon are made is distinguished by a simplicity that is kind of refreshing. They are obviously not true to life, yet they seem to capture something fundamental about the human condition. And in these figures, the artist—really, the Palestinian artist working in the Byzantine idiom—has somehow retained the line and form emphasis that is so characteristic of the best of the old ornamented manuscripts.

The composition of the icon is a beautiful example of how local artistic traditions can interact with and enhance Byzantine styles. The brilliant reds used in the background and clothing vibrate with the gold and pearl details that adorn the halos and books held by the figures. The Palestinians actually have a workshop tradition that can be traced back about 1,800 years—in part because of their long history of creating beautifully illustrated manuscripts.

One thing that captures attention immediately is the four angels that hold Christ’s elliptical glory. This is a classic detail of the Palestinian art style. Even so, the robes of the two lower angels catch my attention. There seems to be a long, comprehensive history of examining the scientific and artistic techniques that have gone into their creation. And with good reason. Both the delicate, textured edges that call to mind something like fur and the flowing ends of their garments are signs of the artist’s technical mastery and creative skill.

Another unique aspect of this depiction is the placement of the Virgin Mary before a sapling of red-flowered myrtle, a type of flowering bush. Myrtle has a strong association with the Burning Bush: biblical Hebrew describes the plant in this way—”And the angel of the Lord appeared unto him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush: and he looked, and behold, the bush burned with fire, and the bush was not consumed” (Exod. 3:2, KJV). The icon’s connection of the Burning Bush in biblical history to the present in Santa Katarina emphasizes a clear line of significance from the past to the present.

In sum, the Ascension icon from Sinai attests to the artistic innovation and skill of Palestinian workshops. It is a beautiful piece that demonstrates how local traditions could enliven and diversify the wider world of Byzantine art.

Conclusions on the icon of the Ascension of Sinai

The analysis of the icon of the Ascension in the Sinai Monastery reveals a work of exceptional importance for the understanding of medieval art and the Palestinian artistic tradition of the 9th-10th centuries, which uniquely combines the theological weight of the subject with artistic originality in the rendering of figures and symbols, while the presence of elements such as the inscription ‘Son of God’, the depiction of the Virgin Mary in front of the sapling symbolizing the Flaming Vato, and the particular arrangement of angels and apostles, give the work a special place in the history of Byzantine art. Over the centuries, the icon remains a remarkable example of the synthesis of local and universal elements in medieval Sinai art.

elpedia.gr

Bibliography

Weitzmann, K. (1963) Thirteenth Century Crusader Icons on Mount Sinai.

Spain, S. (1980) The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai, The Icons, Vol. I: From the Sixth to the Tenth Century.

Anderson, J.C. (1979) The Illustration of Cod. Sinai. gr. 339. The Art Bulletin.

Nicolopoulou, M. (2002). Image from the British Museum of St. George on horseback: issues of art and technique.