In the rich tradition of Greek mythology, Aeolus holds a special place as the master and guardian of the winds. His figure is a characteristic example of the ancient Greeks’ tendency to personify natural forces, attributing them with divine or semi-divine qualities. According to the most prevalent version of the myth, Aeolus resided on a floating island, Aeolia, where he had the power to control the winds at will. This figure became widely known mainly through Homer’s Odyssey, where he is depicted offering assistance to the wandering Odysseus by giving him a bag containing all the adverse winds. However, Aeolus is not the absolute god of the winds in Greek mythology, as he would later evolve in Roman tradition, but a mortal who received from the gods the privilege to control the airy elements (Decharme). The complexity of the myth is further enriched by the existence of different versions regarding his origin and nature, as well as the merging of different mythological figures bearing the same name.

1. The figure of Aeolus in the Odyssey

1.1 Aeolus as king of Aeolia

The first and most well-known reference to Aeolus as the guardian of the winds is found in the 10th rhapsody of Homer’s Odyssey. There he is presented not as a god but as a mortal king, who has received from the Olympian gods the exceptional privilege to control the winds. His residence is placed on the mythical island of Aeolia, which is described as a floating island surrounded by a bronze, impenetrable wall. The geographical identification of Aeolia has been the subject of research with prevailing theories placing it in the Lipari Islands of Sicily, where volcanic activity could explain the changing winds of the area.

1.2 Odysseus’s Encounter with Aeolus

The Unique Domesticity of a Wind God

Homer’s epic tale vividly recounts the pivotal meeting between the astute Odysseus and Aeolus, the esteemed master of the winds, a narrative that unfolds with rich detail and evocative imagery. Aeolus, renowned for his hospitality, extends a warm welcome to the weary Odysseus and his loyal companions, offering them respite and sustenance within the opulent confines of his majestic palace. For a full lunar cycle, a month of days, Aeolus graciously hosts the wandering hero and his crew, providing them with the comforts of his lavish abode. The description of Aeolus’s prosperous life is painted with broad strokes, emphasizing his idyllic family life, a harmonious existence shared with his wife and their twelve offspring—six sons and six daughters—who have solidified their familial bonds through marriage to one another. This particular motif of intra-family unions stands as a distinctive element, setting the Homeric portrayal of Aeolus apart from other mythological figures bearing the same name. In a way, this unique family structure mirrors the tightly knit communities found across the USA, where family ties are often deeply valued and celebrated, reflecting a sense of unity and shared heritage. This emphasis on family cohesion, whether in ancient Greek myth or modern American society, underscores the enduring human fascination with familial bonds and their role in shaping cultural identity.

1.3 The mythical bag of winds

Upon Odysseus’s departure, Aeolus offers him an exceptional gift: a bag made of oxhide, in which he has imprisoned all the winds contrary to his destination. The king of the winds, demonstrating his authority over the airy elements, leaves only the Zephyr free to blow favorably for the hero’s journey to his homeland. This Aeolian intervention in the natural forces is a characteristic example of the ancient Greeks’ perception of nature as subject to external control by supernatural forces.

1.4 The curiosity of the companions and the disaster

The tragic development of the episode occurs when, while Odysseus sleeps exhausted as they approach Ithaca, his companions, driven by curiosity and greed, open the bag believing it contains treasure. The winds are released with force, causing a storm that drives the ship away from its destination, returning it to the island of Aeolus. This adventure highlights a timeless theme of Greek mythology: the destructive consequences of human curiosity and greed when opposed to divine will.

1.5 Aeolus’s refusal for a second help

Upon returning to Aeolia, Aeolus refuses to help Odysseus again, considering the failure of the journey as a sign of divine disfavor. Characteristically, the guardian of the winds dismisses the hero with the words: “Leave quickly from the island, most wretched of mortals! I am not allowed to host and help a man hated by the blessed gods.” This stance of Aeolus underscores the perception of divine order and fate in ancient Greek cosmology, where the favor or disfavor of the gods determines human fortune, while also highlighting Aeolus’s respect for divine will, despite the special authority granted to him.

2. The multiple identities of Aeolus

2.1 Aeolus as the progenitor of the Aeolids

The complexity of the myth of Aeolus is particularly highlighted when examining the different mythological traditions associated with this name. Alongside the Aeolus of the Odyssey, who is primarily presented as the guardian of the winds, another Aeolus appears in Greek mythology, the progenitor of the Aeolids and the eponymous hero of the Aeolic race. According to the most prevalent tradition, this Aeolus was the son of Hellen and the nymph Orseis, brother of Dorus and Xuthus, and therefore, through his father, grandson of Deucalion. The distinction between the various homonymous figures is the subject of extensive Aeolus study in modern mythographic research (Pryke).

2.2 Different genealogical traditions

Ancient sources present various genealogical traditions for Aeolus, which intensifies the confusion between the different figures. According to some versions, Aeolus of the winds was the son of Poseidon and Arne or Melanippe, while other sources consider him a descendant of Hippotes. The need to systematize these contradictory traditions led later writers, such as Diodorus Siculus, to distinguish three different figures with the name Aeolus, attempting to reconcile the different myth traditions into a coherent narrative.

2.3 Confusions between the homonymous mythological figures

The comparative examination of the different traditions shows that ancient writers often confuse the various Aeoluses, attributing to them conflicting characteristics and genealogies. This challenge is intensified by the tendency of later writers to try to harmonize pre-existing contradictory traditions. Particularly in the Hellenistic period, there is an effort to systematize the myths, which often leads to further complications. As Apollodorus points out in his Library, this confusion between the various Aeoluses may reflect the merging of local mythological traditions during the formation of the pan-Hellenic mythological canon.

2.4 Aeolus as a historical figure

Another dimension in the study of the figure of Aeolus lies in the attempt of some ancient and later writers to interpret him as a historical figure. According to this rationalizing approach, Aeolus was a real king of the Aeolid islands who, due to his special knowledge of weather phenomena and winds, gained the reputation of the master of the airy elements. This interpretative tendency, which dates back to antiquity, represents an early attempt to disconnect the myth from the supernatural element and integrate it into a historical context.

2.5 Aeolus in comparative mythology

The examination of the myth of Aeolus in the context of comparative mythology reveals interesting parallels with mythical figures from other cultures related to the control of winds and weather phenomena. In the Hellenistic period, Aeolus is often identified or paralleled with corresponding deities of other Mediterranean cultures. For example, in Roman tradition, the figure of Aeolus evolves into a more complete personification of the winds, with expanded powers and responsibilities compared to the Greek counterpart. This evolution of the myth demonstrates the dynamic nature of mythological traditions and their adaptability to different cultural contexts, as well as the timeless significance of the personification of natural forces in the human effort to understand and interpret the natural world.

The theological and symbolic dimension of the myth

3.1 The control of natural forces as a divine privilege

The figure of Aeolus as the master of the winds reflects a fundamental dimension of ancient Greek religious thought: the perception that natural forces are subject to divine control and intervention. The control of the winds, these unpredictable and sometimes destructive air currents, represents the desire of humans to explain and tame natural forces through their personification. Unlike other deities associated with the elements of nature, Aeolus is presented as an intermediary, a mortal who has received divine privileges, which underscores the hierarchical structure of the world in Greek cosmology. The assignment of control of the winds to a figure that lies between the divine and human levels reflects the complexity of the ancient Greek perception of the divine.

3.2 The allegorical interpretation of Aeolus as an astronomer

Already from antiquity, allegorical and rationalizing interpretations of the myth of Aeolus were developed. Particularly widespread was the interpretation of Aeolus as an experienced astronomer and meteorologist, who, thanks to his knowledge of the stars and weather phenomena, could predict the changes of the winds. This allegorical reading of the myth, which is found in authors such as Palaephatus and Euhemerus, represents an early trend of rationalizing mythical narratives. This approach, which was further developed during the Hellenistic period, is part of a broader trend of disconnecting myths from the supernatural element and integrating them into a framework of human experience and knowledge.

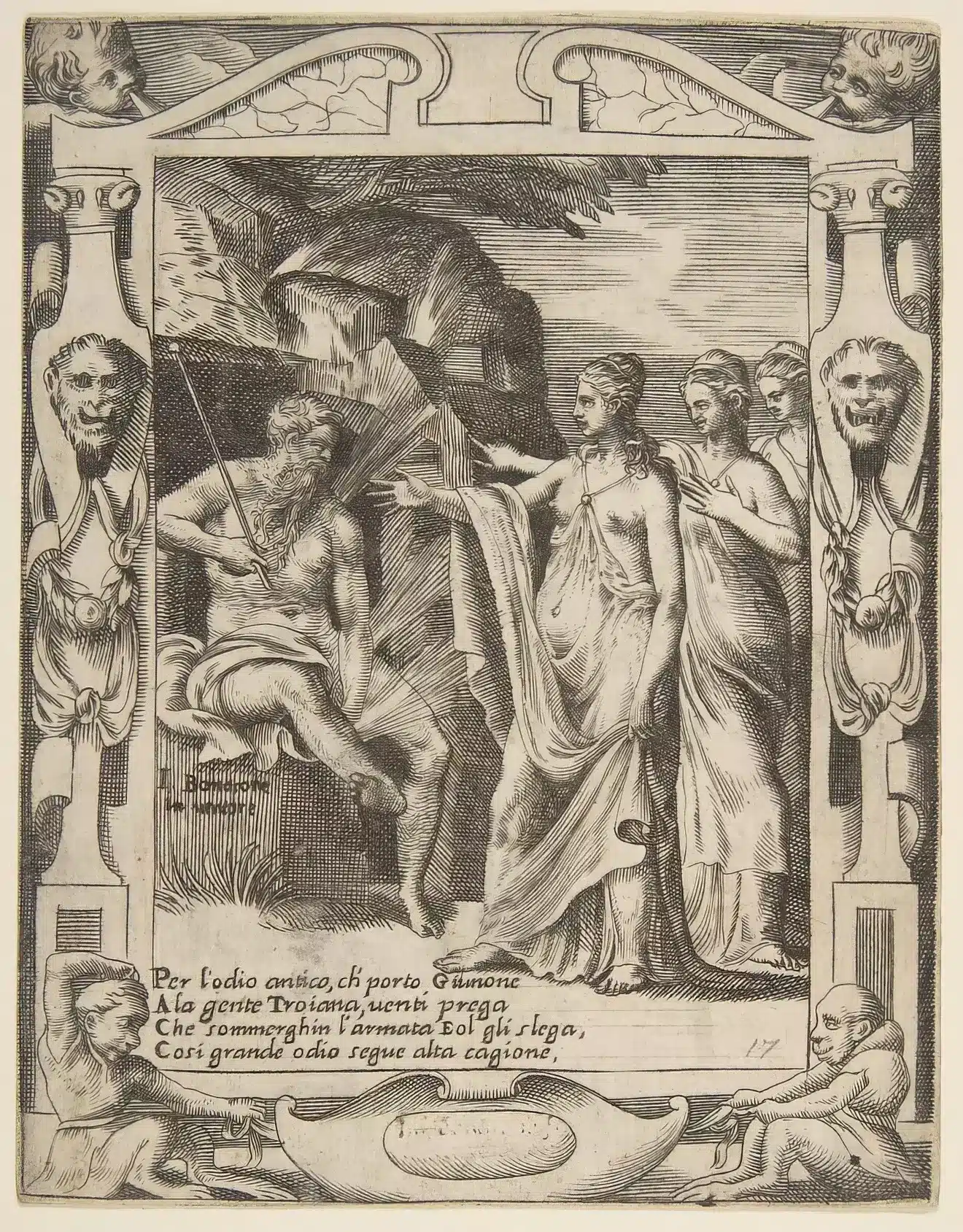

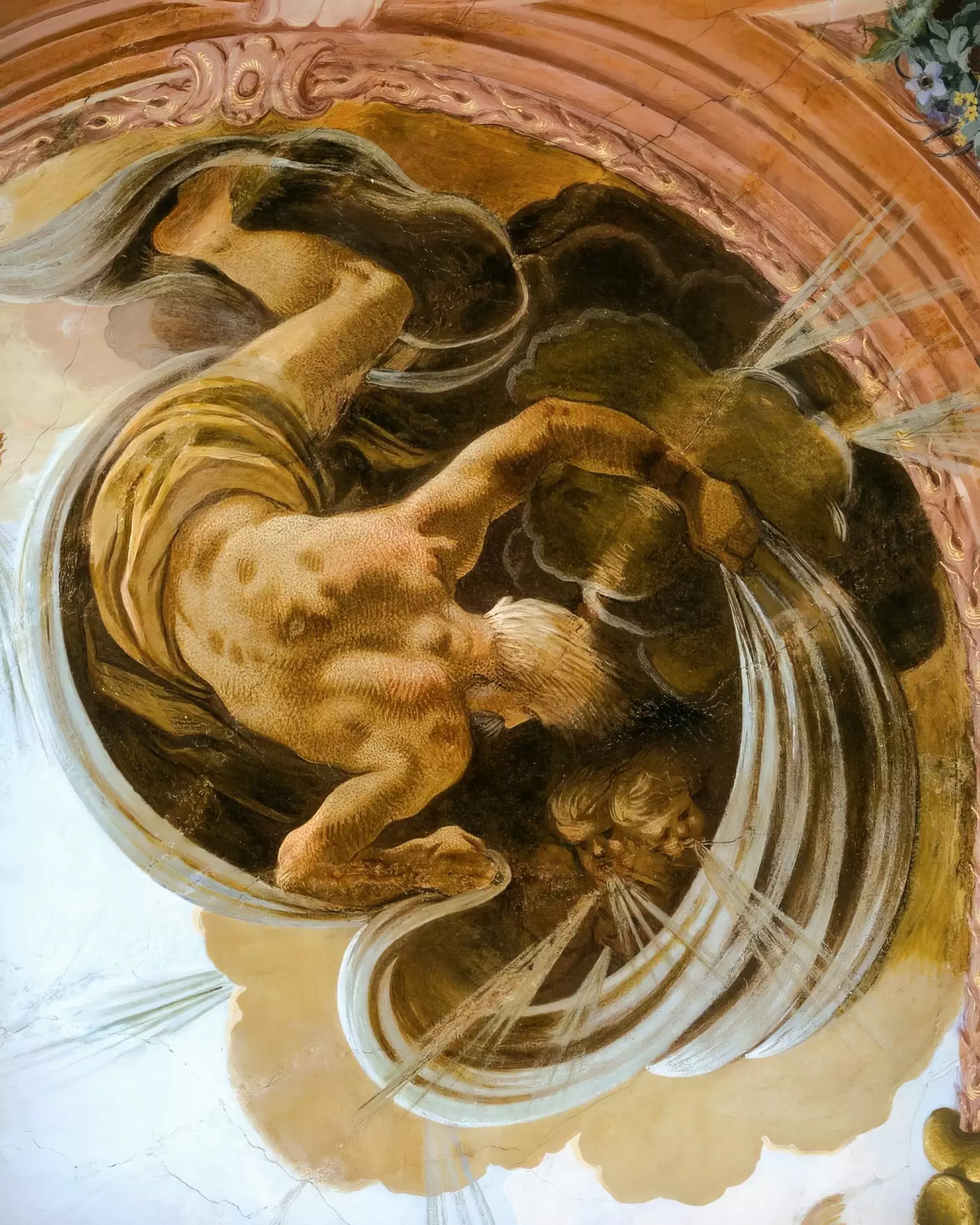

3.3 The survival of the myth in later art and literature

The figure of Aeolus as the master of the winds has survived with remarkable vitality in later art and literature. From the relief depictions of antiquity to the paintings of the Renaissance and Baroque, the guardian of the winds is a recurring theme in visual art. Particularly impressive is the depiction of the scene of the delivery of the bag of winds to Odysseus in numerous works, such as in the famous 17th-century painting by Isaac Moillon titled “Aeolus Delivers the Winds to Odysseus”. In literature, the myth of the guardian of the winds has inspired numerous references and reinterpretations, from the time of Roman poetry with Virgil to modern literature. This timeless allure of the figure of Aeolus testifies to the dynamic of ancient myths to continually offer new interpretative frameworks for understanding the relationship between humans and natural forces and the divine.

The Enduring Legacy of Aeolus

Navigating the Celestial Order

In the grand tapestry of ancient Greek cosmology, the myth of Aeolus, the guardian of the winds, stands as a testament to humanity’s enduring quest to comprehend the natural world. This myth, intricately woven with personification and myth-making, reveals a sophisticated understanding of the forces that shaped their lives. Rather than viewing the winds as mere atmospheric occurrences, the ancient Greeks imbued them with divine agency, placing Aeolus as a pivotal figure in their celestial hierarchy. This perspective, much like the deep influence of Cretan Byzantine iconography, which is prominent in the USA through the evolution of unnaturalism in postmodern painting, illustrates how cultural interpretations of the world manifest in diverse ways. Aeolus’s role as a mediator between the divine and human realms underscores the hierarchical structure that permeated ancient Greek religion, where gods, demigods, and mortals existed in a carefully defined order. The complexities surrounding Aeolus’s genealogy, and the conflation of various homonymous figures, further highlight the dynamic evolution of mythological narratives. These discrepancies are not merely errors but reflections of the fusion of local and pan-Hellenic traditions, each contributing unique nuances to the overarching myth. The survival of Aeolus in art, literature, and popular imagination across centuries speaks to the timeless appeal of stories that seek to explain the intricate relationship between humanity and the unpredictable forces of nature. This enduring fascination underscores the human desire to find meaning and order in the face of the uncontrollable, a theme that resonates deeply within the collective human experience.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the origin of Aeolus as the guardian of the Aeolian currents?

The origin of Aeolus presents remarkable variations in different mythological traditions. According to the Homeric narrative, Aeolus who controls the winds is a mortal king, who received from the Olympian gods the privilege to manage the airy currents. Other sources consider him the son of Poseidon and Arne or Melanippe, while there are also traditions linking him to Hippotes. This multiplicity of genealogical narratives reflects the merging of local mythological traditions.

Why is there confusion between the different figures bearing the name Aeolus in the ancient myths of the winds?

The confusion arises from the parallel existence of at least three distinct mythological figures with the name Aeolus in Greek tradition. The first is the Homeric guardian of the winds, the second the progenitor of the Aeolids and son of Hellen, and the third the son of Poseidon. The later mythographic tradition, attempting to reconcile these different narratives, created further complications in understanding and distinguishing the different Aeoluses and their respective mythological cycles.

How is the relationship of Aeolus with the winds presented in Homer’s Odyssey?

In the Odyssey, Aeolus appears as the king of the floating Aeolia, equipped with the authority to command the winds. During his meeting with Odysseus, he offers him hospitality for a month and then provides him with a bag in which he has enclosed all the contrary winds, leaving only the Zephyr free to blow favorably. This intervention of the guardian of the airy currents in the fate of the hero underscores his role as a mediator between divine will and human fortune.

Where is the mythical Aeolia, the kingdom of the guardian of the winds, geographically located?

The geographical identification of the mythical island of Aeolia remains a subject of scholarly debate. The prevailing theory places it in the Lipari Islands (Aeolian Islands) near Sicily, a region known for volcanic activity and unpredictable weather conditions. Some scholars propose alternative locations, including Stromboli or other islands of the central Aegean, but ancient sources do not provide definitive evidence for the exact location of the island of the airy currents.

What is the symbolic significance of the myth of Aeolus as the master of the airy currents?

The myth of Aeolus as the regulator of the winds reflects the human need to control unpredictable natural forces. It symbolizes the ancient Greek perception of cosmic order, where even the most unstable elements are subject to a hierarchical system of control. At the same time, the episode with the bag of winds in the Odyssey serves as an allegory for the destructive consequences of human greed and curiosity. The archetypal dimension of this mythical model explains its timeless survival in various cultural contexts.

How did the figure of Aeolus as the guardian of the airy elements evolve in Roman mythology?

In Roman tradition, Aeolus (Aeolus) acquired a more divine character, evolving from a manager to a father and king of the winds. Virgil in the Aeneid presents him as a powerful deity residing in a cave where he keeps the turbulent winds imprisoned. This evolution reflects the Roman tendency towards more centralized and hierarchical perceptions of the divine. At the same time, his iconography was enriched with new elements, such as the scepter of authority over the airy currents, enhancing the imperial symbolic dimension of his figure.

Bibliography

- Megapanou, Amalia. Faces and other proper names: mythological-historical up to the … 2006. books.google.gr.

- Varinus, (Camers, Bishop of Nocera), and Nikolaos Glykys. Dictionarium magnum. 1779. books.google.gr.

- Decharme, Paul. Mythology of Ancient Greece. 2015. books.google.gr.

- Pryke, Louise M. Wind: Nature and Culture. 2023. books.google.gr.

- Chrestomathia graeca. 1801. books.google.gr.

- Homerus. L’Odyssée d’Homère. 1818. books.google.gr.

- Ausführliches Lexicon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie. 1890. books.google.gr.