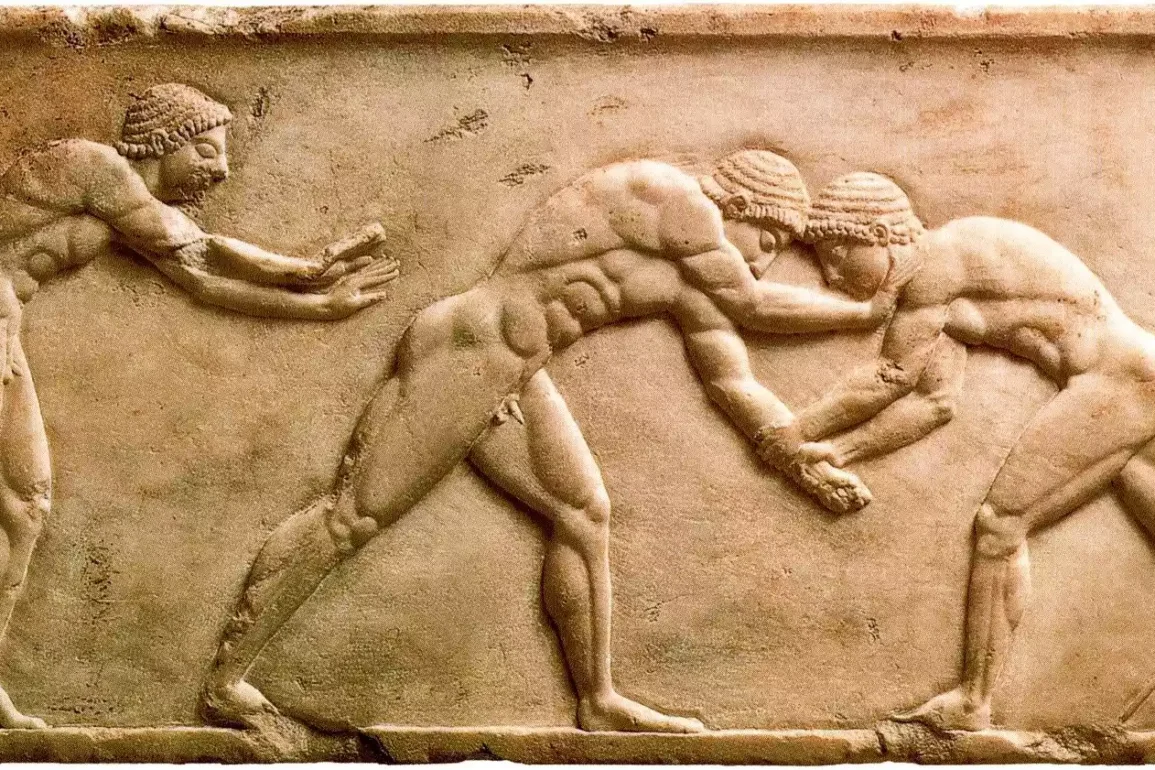

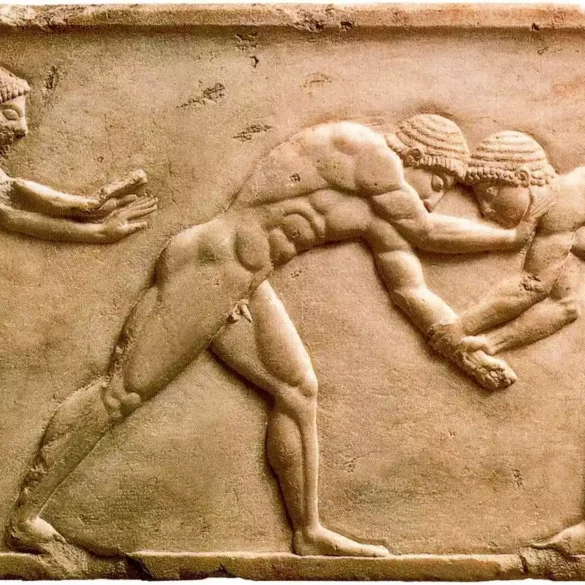

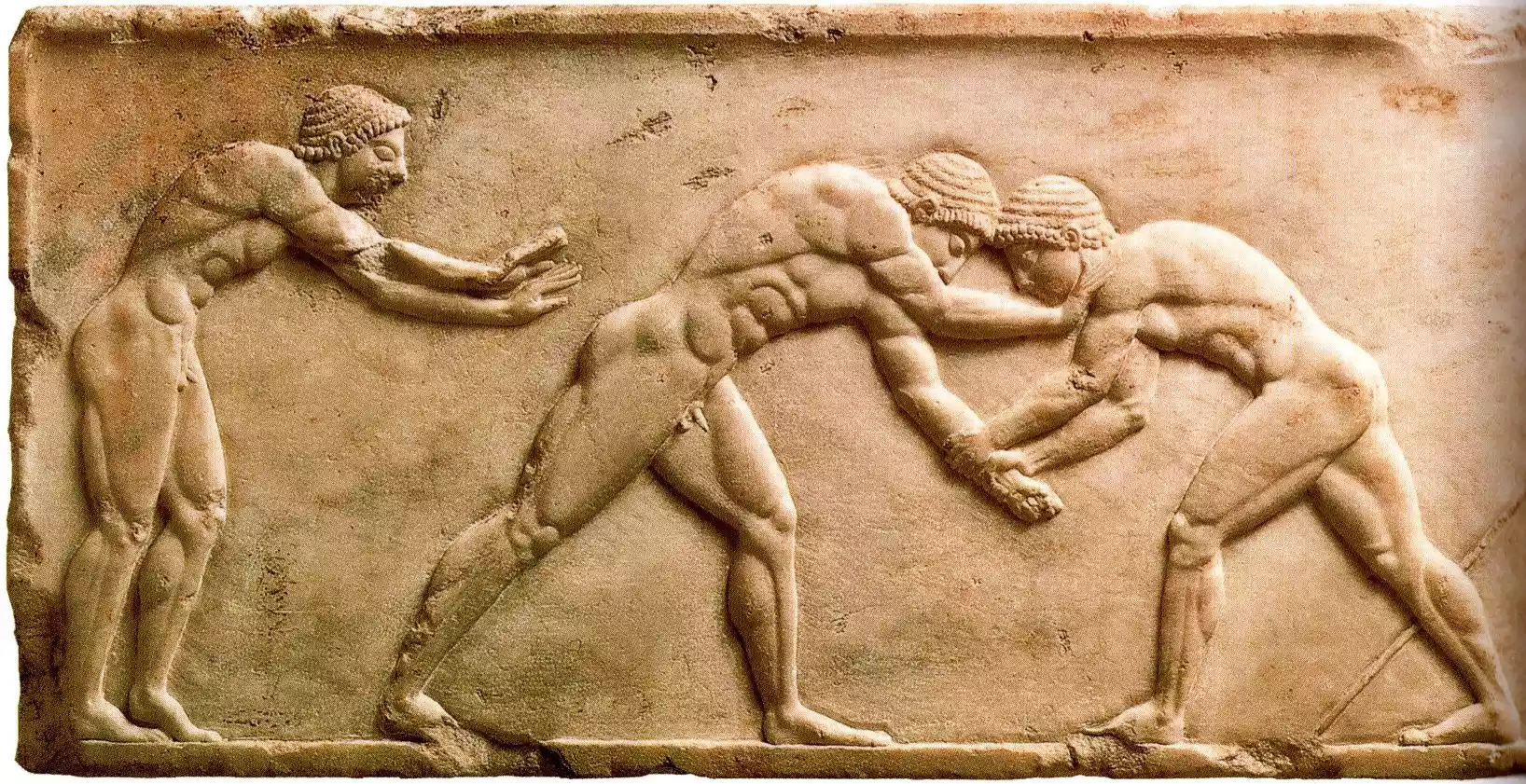

This Stele, Embedded In The Walls Of Athens During The Persian Wars, Depicts Athenian Athletes Training. The Scene Features A Runner At The Starting Line, Wrestlers, And A Young Man Checking The Tip Of His Javelin.

Circa 510 Bc, National Archaeological Museum Of Athens

In ancient Athens, funerary stelae were poignant, poignant expressions of remembrance and commemoration during the classical era (5th-4th century BC), not so different from the elaborate grave markers found in cemeteries across the United States today. Yet, while the bronze plaques nearly always found in a US cemetery make a sincere but paltry effort at revealing the essence of the individual buried below, the opportunities for self-expression in death that were so fervently embraced by ancient Athenians are utterly unique in human history. Indeed, the stelae, as one US scholar has said, were “sculpted with a purpose.” And that serves as my purpose in this essay: to help you see just how the Athenian funerary stelae of the classical era were artistic expressions of the identities of those who were buried beneath them.

Deep in the bustling center of ancient Athens—among the splendid temples and public edifices, not to mention the vibrant busy streets—one could find tranquility in the final resting places of the dead. The stelae, placed upright, like the living, were positioned for effect. They almost always faced the road, for most funerary stelae served as advertisements of sorts, proclaiming to passersby that the deceased had once lived here and belonged to this community. “Look on this,” the stelae seemed to cry. “This is my daughter,” or “this is my son.” And many were not content with mere words. They went for what could be done in stone, to make clear what had to be made clear, casting into bas relief what could not be elegantly stated in writing on the stele’s front. “Here is a likeness of my child.”

Evolution of Funerary Stelae in Classical Athens

The Early Funerary Stelae of the 6th Century BC

The funerary stelae of ancient Athens began as simple, tall shafts (stelae) in the late 6th century BC. These early stelae were often topped with sphinxes, mythical creatures considered protectors of the dead (Stupperich, 1994). However, soon the shaft of the stele began to be carved with relief depictions portraying the deceased themselves. This transition marked a significant shift in the expression of funerary art, as the focus shifted from symbolic elements to the representation of the individual. The young were often depicted as athletes, holding discs or oil flasks, while men were presented as warriors. These figures, standing tall and imposing, resembled the kouros statues of the time, both in posture and detail (Leader, 1997). Despite their idealized nature, these depictions offered a more personalized representation of the deceased compared to the early kouroi of the tombs.

As the 6th century came to a close, the funerary stelae began to incorporate more varied and personal scenes. A notable stele depicts a young man with his little sister, while another fragmentary work shows a mother holding her child (Squire, 2018). These tender family scenes added a more human dimension to the funerary stelae, moving away from the impersonal, heroic representations of the past. Additionally, the funerary stelae began to capture distinctions of age and profession with greater clarity. The young continued to be depicted as athletes, mature men as warriors, while the elderly were often shown leaning on a cane, accompanied by a dog. This differentiation reflected a more complex understanding of the stages of life and social roles in ancient Athens.

Eastern Greek Influences

Around 530 BC, the sphinxes on the funerary stelae were replaced by simpler finials with spiral foliage (anthemia). This change is attributed to the influence of Eastern Greece, which played a significant role in the evolution of Athenian art during that period. However, despite the abandonment of the slender, tall shaft in Athens before the Persian Wars, this type of stele survived on the islands for a longer time, reflecting regional variations in funerary customs.

As the 6th century BC came to an end, the funerary stelae of ancient Athens had undergone significant changes. From the symbolic, idealized representations of the early stelae, they evolved into more personalized and emotionally charged monuments. This transition reflects the changing perceptions of identity, family, and the cycle of life in ancient Athens, offering a vivid picture of the society of the time.

The Artistic Zenith of Athenian Grave Markers in the 5th Century BC

The funerary stelae of ancient Athens created during the 5th century BC exhibit an extraordinary artistic development that seems almost parallel to the artistic boom that accompanied the Victorian era in England. Sculptors, heavily influenced by classical art, were incorporating realism and expressive power into their works like never before. Figures carved on funerary stelae took on greater plasticity and naturalism and seemed almost to come alive (or not quite die, to be more accurate) in the soft, flowing lines of their bodies and the meticulously rendered folds in their garments. Stelae were becoming more like lifelike portraits, and this attention to detail and anatomical accuracy is reminiscent of the portraiture that became so popular centuries later.

Prior to this era, facial expressions had been stylized and idealized, but now they conveyed a whole spectrum of emotions and individuality. The eyes, often sculpted with a delicate shading that evoked a sense of depth and warmth, suggested an inner life and a capacity for affection. Subtle, restrained smiles added a touch of humanity and warmth, movements away from the previously standard stoic expressions. This realism allowed the funerary stelae to capture the essence of the deceased in a way that had never been done before—and achieved a powerful memorial that survived long after those being remembered had gone.

By the 5th century BC, funerary stelae were taking an even more complex form, featuring merrily multiple figures. Families were often the main subjects of these more intricate sculptures, with some displays including the three or four members who made up the intimate unit of a household. And they were showing off their figures in soft, not-quite lifelike poses, which some scholars interpret as signs of a move toward “naturalism”—the representation of forms as they appear in nature.

These family scenes often incorporated subtle narrative elements that hinted at the personal stories and relationships portrayed that went far beyond mere representation. The gestures and postures of the figures—a delicate touch of the hand, a gentle tilt of the head, the angle of the body—conveyed so much meaning that the viewer could almost sense the lives and relationships shared by the depicted figures. The funerary stelae became imbued with this narrative power, allowing the depicted families to almost speak. The stelae took on the power of good writing—stories with an immediacy and emotional resonance that made them good memorials, much like a well-written epitaph or the narrative power of a simple elegy.

The Integration of Symbolism and Decorative Elements

Despite the move towards greater realism, the funerary stelae of the 5th century BC did not entirely abandon symbolic and decorative elements. Objects such as lekythoi (oil flasks) and birds, with their connotations of ritual and the soul, continued to appear as secondary motifs. The spiraling tendrils and flowers added a sense of decorative grace, framing the central figures with delicate beauty.

However, these symbolic elements tended to be more discreet, subordinated to the central iconography of the human form. It was as if the symbolism had become a secondary language, a layer of meaning that underscored and enhanced the main narrative. Through this balance of realism and symbolism, the funerary stelae managed to be both immediate and expressive, while maintaining a sense of mystery and deeper meaning.

The 5th century BC represents the pinnacle of funerary stele art in ancient Athens. Through the combination of realism, narrative elements, and symbolism, these monuments managed to capture the essence of the human experience in a way that remains moving even today. They stand as a dynamic testament to the skill of ancient artists and a lasting reminder of the timeless power of art to connect the past with the present.

Circa 550 Bc. Height 46 Cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Catalogue Number: Nm 28.

Funerary Stelae and Social Roles in Classical Athens

Depictions of Women and Family Bonds

The funerary stelae of the classical period offer a valuable insight into the roles and relationships of women in ancient Athens. In many stelae, women are depicted as wives and mothers, seated in domestic settings and surrounded by their children and husbands. These tender family scenes suggest the central role of women in maintaining the household and raising the next generation.

However, as Leader points out in her article “In death not divided: Gender, family, and state on classical Athenian grave stelae” (1997), these depictions should not be seen merely as passive reflections of reality. Instead, they can be interpreted as ideals and aspirations, expressions of how Athenian society perceived and accepted gender roles. Women, even in death, were depicted in a way that reinforced the gender norms and expectations of the time.

Iconography of Male Virtue and Duty

Equally revealing are the representations of men on the funerary stelae. Men are often depicted as warriors and citizens, emblems of their bravery and dedication to the city-state. These heroic figures with their proud stance and fearless expression embody the ideals of male virtue – courage, strength, and self-sacrifice.

At the same time, men are also shown in more intimate roles, as husbands and fathers. Farewell scenes, where a man tenderly embraces his wife or holds his child’s hand, capture the importance of family bonds even for those who bore the duty of public life (Stupperich, 1994). This duality suggests the complexity of masculinity in classical Athens, where personal ties and civic obligations were inextricably linked.

Stelae as Public Proofs of Social Prestige

Beyond commemorating the dead, the funerary stelae also served as visible statements of social prestige and status (Squire, 2018). The erection of an elaborately carved stele, often at expenses exceeding legal obligations, was a way for a family to display its wealth and status. The depictions of the deceased in luxurious garments and grave goods served as an indication of their prominent status, a visual signal of their place in the city’s hierarchy.

At the same time, the stelae of less affluent citizens, though more modest in scale and decoration, testified to a sense of individual dignity and social inclusion. Even a humble monument could underscore the deceased’s position as a member of the citizen body, with all the rights and responsibilities that entailed.

Through the lenses of gender, family, and social status, the funerary stelae of classical Athens offer a vivid picture of the life and values of the time. Like a window into the past, they allow us to see how the ancient Athenians perceived themselves and their place in the world, even in the face of mortality. These stone monuments, in their silent eloquence, continue to speak of the hopes, fears, and ideals of a society long passed into history.

The Legacy of Funerary Stelae in Art and Culture

Influence on Later Greek Art

The artistic and emotional power of the classical funerary stelae left an indelible mark on later Greek art. Sculptors of the Hellenistic and Roman periods continued to draw inspiration from the compositions and techniques of their predecessors, adapting and reinterpreting the motifs to suit the aesthetic preferences of their times.

In Hellenistic funerary monuments, for example, we can discern the influence of the classical stelae in the emphasis on emotion and narrative. Hellenistic artists adopted the use of gestures and body language to convey complex emotions and relationships, building upon the innovations of their forebears. However, they did so in a way that was distinct, taking into account the refined tastes and emotional expressiveness that had become the hallmark of Hellenistic aesthetics.

Even in Roman art, the influence of Greek funerary stelae remained strong. Roman artists admired and emulated Greek models, incorporating elements of classical design into their own funerary reliefs and sculptures. While they adapted these forms to Roman funerary customs and imperial symbolism, their debt to the legacy of Greek stelae remained clear.

Timeless Cultural Significance

Beyond their artistic influence, the funerary stelae of classical Athens maintain a timeless cultural significance. As tangible connections to the past, they allow us to imagine the lives and experiences of people who lived thousands of years ago. Through these stone representations, we can discern the hopes, fears, and values of a society that shaped the foundations of Western civilization.

Today, these ancient monuments continue to move us with their human truth. When we stand before a classical stele, gazing into the eyes of a mourning mother or the silent determination of a warrior, we feel a sense of connection that transcends time and culture. They remind us of our shared humanity, the bonds that unite us even across the chasms of centuries.

In this sense, the funerary stelae are not merely objects of aesthetic admiration, but also bearers of cultural memory. Through their enduring presence, they invite us to reflect on our own mortality and our place in the continuum of human experience. They urge us to ask: What will we leave behind? How will we be remembered by those who come after us?

In the end, perhaps this is the greatest gift of the funerary stelae: an invitation to reflection, to see our own lives through the lens of eternity. As we stand in the shadow of these ancient monuments, we cannot help but wonder about the stories the stones will tell of us when we are gone. In this moment of connection, the past, present, and future become one, woven into the eternal tapestry of human experience.

The funerary stelae of classical Athens, in their silent eloquence, continue to speak of the hopes, dreams, and struggles of those who lived and loved so long ago. They are a lesson in the timelessness of art and the enduring power of human connection. As we gaze upon these ancient faces, we cannot help but ponder our own place in the vast tapestry of human experience.

Athens With The Head Of A Boxer.

Circa 540 Bc. Height 23 Cm.

The funerary stelae of classical Athens are an integral part of the artistic and cultural heritage of ancient Greece. Through the evolution of their form, iconography, and symbolism, these monuments offer a unique insight into the social norms, values, and beliefs of the time. At the same time, their timeless appeal testifies to the power of art to connect the past with the present and to provoke reflection on our own mortality and place in the world. As we contemplate the significance of the funerary stelae, we draw not only knowledge of ancient Athens but also valuable insights into our own lives and legacy.

elpedia.gr

Bibliography

- Leader, R. E. (1997). In death not divided: Gender, family, and state on classical Athenian grave stelae. American Journal of Archaeology, 101(4), 683-699. journals.uchicag

- Stupperich, R. (1994). The iconography of Athenian state burials in the Classical period. In S. Böhm & K.-V. von Eickstedt (Eds.), ΙΘΑΚΗ: Festschrift für Jörg Schäfer zum 75. Geburtstag am 25. April 1992 (pp. 87-105). Ergon-Verlag. archiv.ub.uni

- Squire, M. (2018). Embodying the dead on Classical Attic grave-stelai. Art History, 41(3), 518-545. academic.oup